* Switch language to english for english version of the article *

This article was first written for the catalogue of the third edition of the Bourgogne Tribal Show, 2018.

“A journey should not be planned by chance. A logical itinerary is required for adventures to be beautiful”.1

Victor Segalen

“The race for the most primitive encounter”2 was in full swing in the 1930s. The intellectual and artistic worlds were moved, horrified and had cause to marvel at the “savage” and his productions. From the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition to films like Lands of the Cannibals directed by Paul Antoine and Robert Lugeon, the public was in a quest for the great “cannibal shiver”.3 At the same period, the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro contributed to the creation of French ethnology. The Dakar-Djibouti mission launched a new era – that of professional ethnology. However, ethnographic expeditions were rather rare and it was generally well-informed amateurs who set off in search of adventure to add objects and previously unknown specimens to collections.

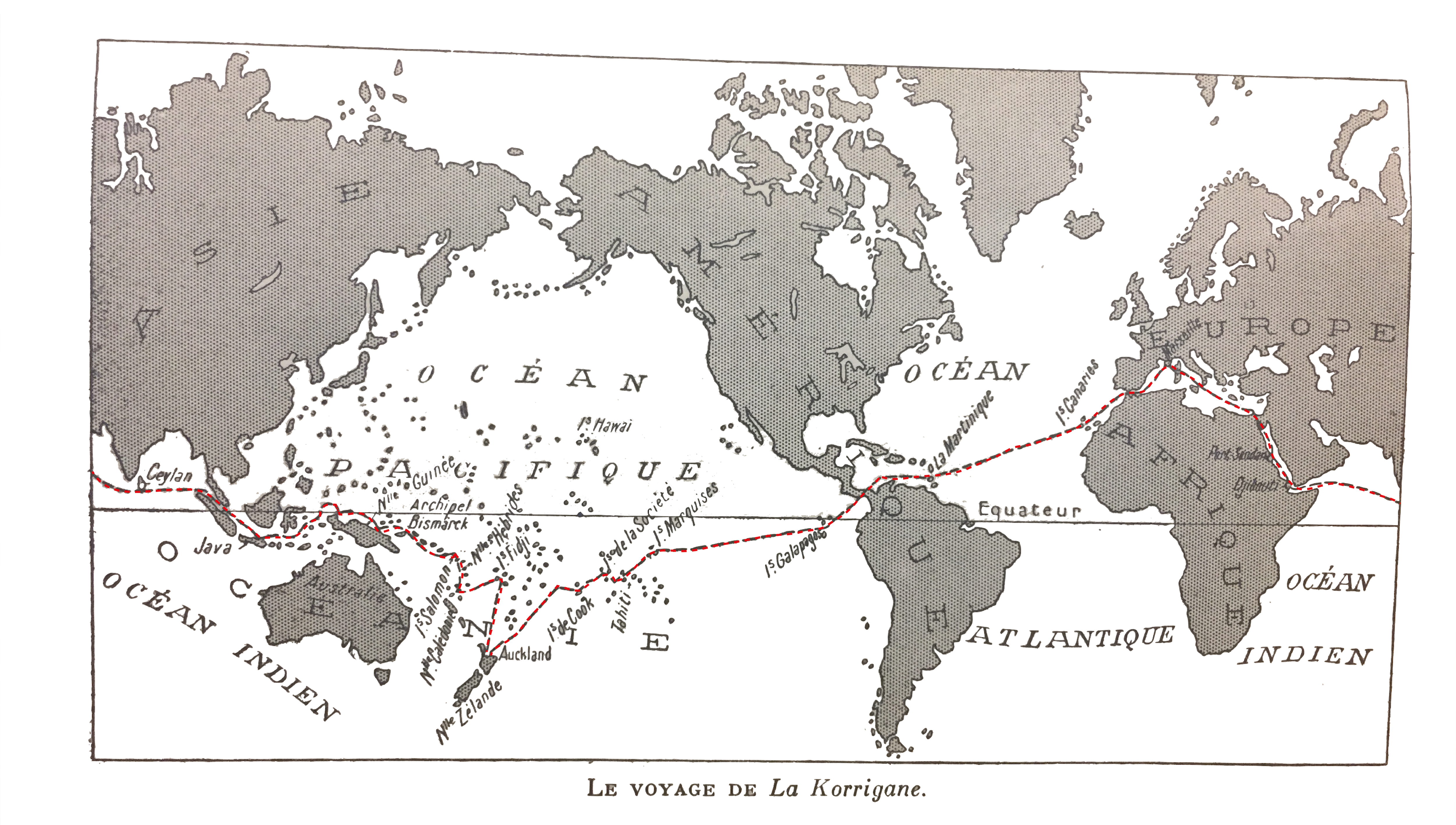

Carte du voyage de La Korrigane. © Van den Broek d’Obrenan, 1939, p. 9.

On 28 March 1934, five friends left the port of Marseilles on the Korrigane. Aboard, Etienne and Monique de Ganay took with them Etienne’s sister and her husband, Régine and Charles van den Broek, as well as Jean Ratisbonne. The members of the expedition had a crew of eight, two young cats and a green parrot similar to Robinson Crusoe’s.4 A naval cadet, Etienne de Ganay was as much in love with the sea as with his wife, Monique, as shown by his marriage proposal: “Would you accept to follow me very far on the oceans?”5 The taste for travelling was equally strong for the van den Broek couple who went on their honeymoon to Tahiti and Java. Brought up with adventure narratives, ethnologists’ writings and Marcel Mauss’ classes, Régine agreed to embark on this two-year journey.

The expedition gained momentum in Oceania. The Korrigans arrived in August 1934 and started collecting extremely important objects and information. The collection was the result of exchanges with islanders, but also of gifts and purchases from the colonists present there. Among the gifts was the very famous grade figure from Malo Island nicknamed the Blue Man. This ni-Vanuatu sculpture belonged to various Western planters before it entered the collections of Marinoni, a trader of Italian origin living on Malekula. After running into debt through gambling, the lawyer Gomichon des Granges liquidated his business and bought the collection. After receiving letters of recommendation from Rivière and Rivet, the trader welcomed the members of the Korrigane in Port-Villa on 23 May 1935. He gave them eight pieces, among them the Blue Man which was to go into the collections of the future musée de l’Homme.While spending several contradictory information about the provenance of this large blue sculpture. After meeting the trader Jones at Vanikoro on Solomon Islands, who confirmed that the Blue Manused to be part of Marinoni’s collections, Monique de Ganay sent a letter to Rivière to let him know that she would send new information, while also sending a letter to Marinoni requesting further information. He replied that he had bought the sculpture from a chief on Malo Island. Monique de Ganay then made notes about the objects given by des Granges.

Sculpture anthropomorphe dite de l’homme bleu, Trrou Körrou, village Sanakas, île Malo, Vanuatu, Paris, musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, inv. 71.1938.42.8.

Collecting was done with great scientific rigour. While objects were accumulating in the bathroom of the ship transformed into an improvised storage area, information, narratives and legends about the objects were written down in notebooks by Monique de Ganay. This scientific rigour is best illustrated by the example of a wooden ring, called nimbalata, bought for 15 shillings by Charles van den Broek from the men of the Emilep clan. With this ring, a legend was recorded by trader Tom Harrisson at Atchin, near Malekula in Vanuatu. “Men in Merak, in the South of Santo, did not know that they could have sexual relationships with their wives and instead, used large wooden rings. One day, men from Atchin visited them. One of them decided to light a fire to cook his meal. He rubbed a stick in the groove in a piece of wood. A woman from Merak helped him brush some dust from the rubbing into the groove. The man immediately made advances to her. She laughed and said: “What do you want to do with me?” Then she gave him the wooden ring used by the men from Merak. As the man did not know what to do with this ring, he penetrated her. Very satisfied with the experience, she described her adventure to her friends who, in turn, wanted to try the experience with their husbands. But the latter did not know how to do it and had to ask women from Atchin to initiate them. To thank the people of Atchin, the men of Merak gave a big party. The members of the Emilep clan took one of the wooden rings as a souvenir and kept it in the men’s house”.6

Etienne de Ganay, Régine Van den Broek, Charles van den Broek, Monique de Ganay, Jean Ratisbonne.

As well as collecting objects, M. de Ganay was asked by the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle to contribute sea creatures to French collections. The whole operation was a success thanks to the National Bureau of Fishing (Office national des pêches) and the International Commission of Oceanography of the Pacific. However, pleasure and entertainment rapidly got the better of the scientific agenda of the mission entrusted to the Korrigans… In effect, the journey was above all marked by spectacular fishing parties between the two men on board who caught sharks and swordfish in New Zealand and Tahiti. Their pride at their prowess is apparent in the photographs of the journey. While the men were particularly interested in the size of their catch, Régine van den Broek was passionate about the shimmering colours of the Pacific fishes. The twenty-five watercolours recently found in the private collection of Régine’s family are evidence of this. They are all carefully annotated with the location and the fisherman’s name, or even with the vernacular name of the fish when she knew it. Régine van den Broek was also fascinated by Polynesian dances which she frequently painted during the voyage.7 Her style, sometimes naïve and coloured, and sometimes precise when she painted fish, always seemed to hesitate between the charm of colour and the faithful representation of a ceremony or a precise event.

Mixing science, adrenalin and contemplation, the Korrigane was the last great expedition in the Pacific. The Korrigans represented the pivot between two epochs: that of great expeditions in search of the “great cannibal shiver” and that of well considered and documented collecting journeys related to budding a French ethnology.

Enzo Hamel & Elsa Spigolon

Traduction de l’article réalisée par Béatrice Bijon.

Image à la une : La « Korrigane » en Nouvelle Guinée au mouillage dans le fleuve Sépik.

1 Citation extraite de DAYNES, 2005.

2 COIFFIER, C., 2001, p. 1.

3 ibid.

4 VAN DEN BROEK D’OBRENAN, C., 1939.

5 COIFFIER, C., 2011, p. 28.

6 COIFFIER C., 2001, p. 120.

7 COIFFIER, C., 2001, p. 178. (Pour les reproductions, voir pp. 176-177)

Bibliography:

- COIFFIER, C., 2001. Le voyage de La Korrigane dans les mers du Sud. Paris, Hazan.

- COIFFIER, C. et K. HUFFMAN, 2011. « Historique d’un chef-d’œuvre, ambassadeur de l’art ni-vanuatu en France ». InLe Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 133, 2e semestre 2011.

- COIFFIER, C., 2014. Régine van den Broek d’Obrenan. Une artiste à bord de La Korrigane. Paris, Somogy éditions d’Art.

- DAYNES, S., 2005. Les yeux de la Korrigane : bilan photographique d’un voyage dans les mers du Sud.Mémoire d’Anthropologie au Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, sous la direction de Pierre Robbe et Christian Coiffier.

- VAN DEN BROEK D’OBRENAN C., 1939. Le voyage de « la Korrigane » : les Îles Marquises, Tahiti, la Nouvelle-Zélande, les Îles Fidji, la Nouvelle-Calédonie, les Îles Loyalty, les Nouvelles Hébrides, les Îles Salomon, Vanikoro, Santa-Cruz, Santa-Anna, Ressnel, les Îles de l’Amirauté, la Nouvelle-Guinée, Bali… Paris, Payot.

1 Comment so far