[Please note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this article may contain images or names of deceased persons in photographs or printed material.]

In the shadow of the extraordinary contemporary paintings, the possum skin coats of Aboriginal Australian people are objects generally little known to the general public. And for good reason! There are only seven ancient examples1 in the world. However, they have been at the centre of a revival involving many Aboriginal communities in the south and south-east of Australia for the last twenty years. For contemporary Aboriginal people, these coats constitute powerful links with their ancestors and are a means of promoting their culture.

Australian possum

Trichosurus Vulpecula

In the nineteenth century, possum2 skin coats were found all along the southern coast of Australia, in Tasmania and on the southern east coast. The skins of possums hunted by men were smoked and left in the sun until they became stiff. They were then sewn together with kangaroo tendons.

These objects were of great importance to the Aboriginal groups who made them. An individual was given a coat at birth, and this was expanded throughout his or her life to between forty and seventy skins in adulthood. Aboriginal people wore this garment both in daily life and in ceremonies, and a coat usually accompanied its owner in death. Coats were also used as blankets and shelter and sometimes as drums, by folding them beforehand.

Woman wearing a possum coat with a baby on her back, 1870s, South Australia, © National Library of Australia.

A possum coat could be worn either way, with the fur facing outwards or inwards. In the second case, the object revealed patterns incised in the skins and decorated with ochre which constituted a sort of identity card for the owner. These motifs gave information on the immediate family, the clan and the places to which a person was linked.

In reality, these three aspects could hardly be dissociated but were thought by Aboriginal people as a coherent whole. It is necessary to look briefly here at the worldview common to most Australian Aboriginal groups to understand the importance of these motifs.

For a majority of Aboriginal groups, there is a mythical time which has several names depending on the language and is generally referred to in the West as the Dreaming or Dreamtime. It is during this Dreaming that the world was shaped by creatures who emerged from the ground and left their mark on the landscape through encounters, loves and conflicts. A particular mountain is the body of an ancestor who died there, a particular ochre deposit is the blood that another lost, and the whole territory is marked by the paths taken by these giants. These Dreaming routes were followed by Aboriginal people who, before the arrival of Westerners, led a semi-nomadic existence. Each group, clan, lineage and individual was thus linked to a set of these 'Dreamings', themselves inscribed in the landscape, and it is these same dreams that are evoked by the patterns engraved on the possum skin coats.3 These motifs thus materialise both Aboriginal people's link with their land and with the ancestors of their group, both human and mythical, a link that they constantly re-actualise by tracing and wearing these drawings on their coats. As contemporary Aboriginal artists Vicki Couzen and Lee Darroch explain: "in south-eastern Australia possum skin cloaks are one of our most sacred cultural expressions as Aboriginal people. Cloaks link us to both our Ancestors, who have gone before us, and to the Land, which we are the Keepers of."4

These extremely valuable objects quickly attracted the attention of European settlers who began to move to Australia at the end of the 18th century. Many of them were acquired at great expense and joined the collections of the biggest Western museums, where these fragile objects often deteriorated considerably due to poor conservation conditions. This partly explains why there are so few of them left today.

But it was not so much this trade that caused the disappearance of the possum coats as the various measures taken by the colonial government to dispossess Aboriginal people of their land and move them to reserves under the control of missionary organisations.

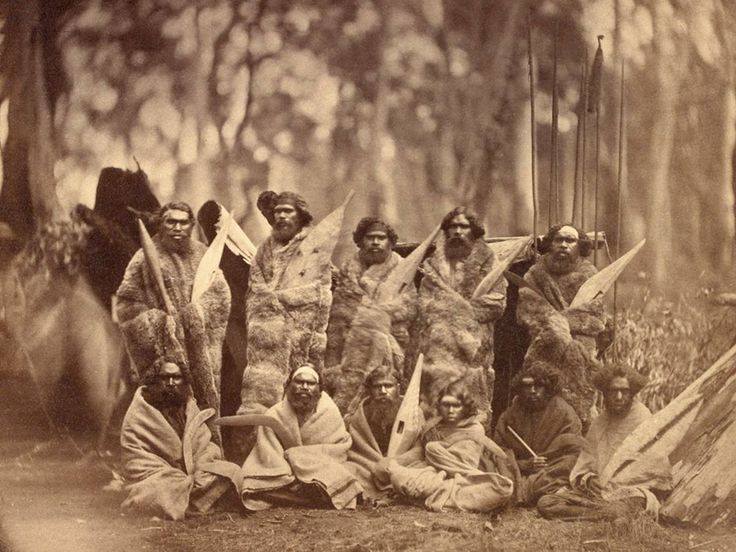

Men of the Kulin Nation, Wurundjeri, c. 1859-1863, Melbourne area,

© Antoine Fauchery

On reserves, many practices were simply forbidden by the missionaries and the Aborigines were forced to abandon them. To compensate for the disappearance of possum coats, the government distributed woollen blankets. These blankets served as substitutes but obviously did not have the same significance as the possum coats, nor did they offer the same degree of protection against cold and damp. Although our tourist imagination, which is well-versed in travel agency posters, tends to see Australia as an endless, reddish desert, in reality the climate in southern Australia is much more varied. Temperatures can fall well below 10°C in winter (June to August), and frequently below zero in some areas such as Melbourne.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the manufacture of possum coats seemed to have come to a complete and definitive halt, and the poorly preserved examples in museums appeared to be the only evidence of this practice.

But the story, for once, ends on an optimistic note. It is precisely because of two of these ancient coats, housed in the Melbourne Museum, that possum coat making is now undergoing a revival. In 1999, a group of eleven Aboriginal artists were allowed to see the two objects, which were too fragile to be exhibited. Three of them, Lee Darroch, Vicki Couzens and Treahna Hamm, with the permission of the elders of the communities from which the coats originated, set about making reproductions of the coats so that they could be seen. As the three artists explained, their approach was aimed at transmitting and revaluing Aboriginal practices: "we wanted our children's children to see the cloaks and know about their rich cultural tradition ".5

The production of these two cloaks has led to a revival of the technique with some modifications. Possums, which have long been hunted, are now a protected species in Australia. The skins used to reproduce the coats are now imported from New Zealand where possums were introduced by Westerners and are considered a pest species because they have no natural predators. These skins arrived in Australia chemically tanned and were much softer than the skins used by Aboriginal people before the 20th century. Contemporary artists have therefore had to find a substitute for the technique of engraving designs, which is only possible on rigid skins. They chose to draw on the skins with pyrography tools. The kangaroo tendons and bone needles traditionally used but very difficult to obtain today were also replaced by waxed needles and thread used for sewing boat sails.

Reproduction of a possum cloak collected around 1872 at Lake Condah (Gunditjmara group), 1999-2002 Vicki Couzens, Lee Darroch, Treahna Hamm.

© National Museum of Australia, Canberra

The two reproductions were exhibited in Melbourne in 2002 and were acquired by the National Museum of Australia in Canberra in 2003. However, the revival did not stop there and several projects to make new coats with Aboriginal communities have since emerged, such as Art of the Skins in the Brisbane region. In 2006, Lee Darroch, Treahna Hamm, Vicki Couzens and Maree Clarck also made a number of coats worn by Aboriginal elders at the opening of the Commonwealth Games in Melbourne.

Contemporary Aboriginal artists have also used these objects in their work, such as Carol MacGregor who used them in her series of photographs entitled Boundary Street (see here). It shows two young Aboriginal girls wrapped in possum coats, posing from behind on the corner of Boundary Street in Brisbane. This street was historically used to mark the 'boundary' that excluded Aboriginal people from the city at night and on Sundays.

Today, beyond their place in museum collections, possum cloaks are emerging as strong cultural symbols for the Aboriginal people of southern and south-eastern Australia and as a tool for dealing with their painful history. "Wearing a cloak, being wrapped in culture, can bring out a range of emotions for Aboriginal people. It is a "powerful reconnection back to their ancestors", says Darroch.6 Making these objects again is thus often described as a form of healing process and a huge source of pride.

Alice Bernadac

Cover picture: Reproduction of a possum coat collected in 1853 at Maiden's Punt (Yorta Yorta group), 1999-2002 Vicki Couzens, Lee Darroch, Treahna Hamm © National Museum of Australia, Canberra.

1 Two are held in Australia at the Bunjilaka Aboriginal Centre in the Melbourne Museum, two at the Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini in Rome, one at the British Museum in London, one at the Smithosian Institution in the United States and one at the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin.

2 Forget Ice Age! The Australian possum, or Trichosurus Vulpecula, is not even a distant cousin of the American possum, which is a mammal. You can actually see that they don't look the same.

3 A more complete article will soon explain the extremely rich and complex concept of the Dreaming. This is just a basic introduction in order to better understand the objects we are discussing. In the meantime, if you wish to learn more about this concept, you can turn to solid and accessible reference publications such as the works by Wally Caruana and Howard Morphy cited in the bibliography at the end of the article.

4 Couzens, Vicki & Darroch, Lee. « Possum Skin Cloaks as a Vehicle for Healing in the Aboriginal Communities in the South-East of Australia » in Kleinert, Sylvia & Koch, Grace. 2012. Urban Representations : Cultural Expression, Identity and Politics. AIATSIS Research Publications. p. 63.

5 Couzens, Vicki & Darroch, Lee. « Possum Skin Cloaks as a Vehicle for Healing in the Aboriginal Communities in the South-East of Australia » in Kleinert, Sylvia & Koch, Grace. 2012. Urban Representations : Cultural Expression, Identity and Politics. AIATSIS Research Publications. p. 65.

6 https://aiatsis.gov.au/exhibitions/possum-skin-cloak

Bibliography:

-

COUZENS V., and DARROCH L., 2012. « Possum Skin Cloaks as a Vehicle for Healing in the Aboriginal Communities in the South-East of Australia » in Urban Representations : Cultural Expression, Identity and Politics. KLEINERT S., & KOCH G., (éds.). Canberra, AIATSIS Research Publications.

-

https://www.sarahrhodes.com/Art-Projects/Possum-Skin-Cloaks-2011-2013/1/thumbs (Photographies des aînés aborigènes du Victoria portant les manteaux réalisés en 2006 pour les Commonwealth Games).

-

https://aiatsis.gov.au/exhibitions/possum-skin-cloak (Avec notamment des vidéos montrant la fabrication d’un manteau contemporain).

-

Exposition Art of the Skins à la State Library of Queensland du 25 juin au 20 novembre 2016.

On Aboriginal art in general:

-

CARUANA W., 1994. L’Art des Aborigènes d’Australie. Paris, Thames & Hudson.

-

MORPHY H., 2003. L’Art Aborigène. Paris, Phaidon.

On Aboriginal people's history:

-

PERKINS R., & LANGTON M., (éds.). 2012. Aborigènes et Peuples Insulaires. Tahiti, Au Vent des Iles.

Pingback: Réclamer la terre au Palais Tokyo | A r t s & S c i e n c e s