*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

Myth: “a widely held story; a misconception; a misrepresentation of the truth; an exaggerated or idealized conception”.1 The specific myth which we are going to consider is the colonial myth of the “discovery” of the Pacific Ocean – Australia and New Zealand being the centre of our study.6 October 1769 is the date when Captain Cook and his men arrived at Poverty Bay, New Zealand. Six months later, on 26 April 1770, Captain Cook and his men reached Botany Bay in Sydney, Australia. At the time, Cook declared the land and newly made it as a territory of the British Empire. On 18 January 1788 the First Fleet arrived in Sydney Cove with the first convicts. Almost 250 years later, this date is still widely remembered and celebrated as Australia Day every 26 January. However, this National Day is far from being acknowledged by all the inhabitants of Australia. Indeed, Indigenous Australians have protested against it and called it 'Invasion Day' . The colonisation of the Pacific was a grand imperial endeavour. All Pacific Indigenous communities have been raising their voices against it and against Captain Cook’s ‘discovery’ of the Pacific. Leading contemporary artists such as Maori Lisa Reihana, Indigenous Australians Gordon Bennett or Michael Cook have been working on deconstructing Captain Cook’s figure through their creative works in order to engage in the debate regarding the ‘idolatry’ of a character who shaped Pacific history.

Through their works, Pacific contemporary artists are “Defying Empire”2 by resisting against the colonisation and the British Empire and the way it has been recorder in history. In other terms, they are acting towards decolonisation. They are redefining and reclaiming their Indigenous identities by “challeng[ing] the subjective history that has been created”.3 Indeed, it is clear that history has often created ‘deified’ representations of the officers of this colonisation such as The Apotheosis of Captain Cook (L’Apothéose du Capitaine Cook1794), a print after Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg and John Webber. The need for contemporary Indigenous artists to bring in a different point of view from the other side of the coin is essential and has been rife on the art scene since the 1990s. All of these works have one common feature: they depict Captain Cook and his actions in a newly ‘discovered’ world. Moreover, these works are a way to deconstruct the Pacific colonial myth through Cook's figure.

Gordon Bennett and Daniel Boyd : historical painting

Gordon Bennett is an Australian artist of Aboriginal descent. I am purposely not defining him only as Aboriginal because he himself does not want to be defined only as such. Indeed, he explains that before the age of sixteen he was not really aware of his Indigenous heritage. Later on, when he decided to “get in touch with [his] ‘Aboriginality’ […] to heal [him]self”Aboriginality) […] pour se soigner »4 he created his own cultural identity, different from the x-ray painting which one can think of when mentioning Aboriginal art. But Bennett wanted to “create a field of disturbance which would necessitate re-reading the image and the mythology”.5 In his series of works such as Australian Icon, Possession Island and Terra Nullius, and Terra Nullius (Icône Australienne, Île de la Possession and Terra NulliusBennett uses a common feature: dots. All of these paintings are quotations from historical paintings of Captain Cook which he covered with pointillism in order to play with two codes of representation: the ‘obvious’ Indigenous Australian tradition and the matrix of photo-mechanical reproductions. But more than being representative of other techniques, pointillism is a way for Bennett to “expose the shadows of official ‘history’ [in order to] map a postcolonial future”.6 Indeed, he is using the dot screen as a unifying factor between the colonial original painting and his own version of it. Through the superimposition of layers – original painting and dot screen – Bennett leaves a space for new versions of history to be written by the viewer, with a view to leaving some room for colonisation to be criticized.

À gauche : Samuel Calvert, Captain James Cook Proclaiming Sovereignty Over the Continent of Australia from the Shore of Possession Island, 1865, National Library of Australia, Canberra, Australie.

À droite : Gordon Bennett, Possession Island (Abstraction), 1991, huile et acrylique sur toile, Tate Modern, Londres, Royaume-Uni.

In Possession Island (Abstraction), 1991, Bennett covers a ‘historical painting’ made by Samuel Calvert with dots. While in the original version of Captain Cook Taking Possession of the Australian Continent on Behalf of the British Crown (Le capitaine Cook prenant possession du continent australien au nom de la couronne britanniquea young aboriginal as Cook’s servant is visible, Bennett here uses the colours of the Aboriginal flag to reverse the meaning of the painting and place “black as presence, not absence”.7 Through his deconstructive approach, Bennett introduces turbulence and chaos in history, deliberately defining Australia’s ‘discovery’ as a misconception created by the western world.

À gauche : D’après John Webber, The Death of Captain Cook, 1784, gravure,

503 x 604 mm, National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, Australie.

À droite : Daniel Boyd, Untitled (DOC), 2016, National Gallery of Australia,

Canberra, Australie.

After Bennett, several artists followed in his footsteps of dot painting. Indeed, more recently, Daniel Boyd has been using a similar technique where he represents historical paintings and covers them with black and white dots in order to create “a beautiful subterfuge”.8 With Untitled (DOC), 2016 Boyd is using a version of a painting of Captain Cook’s Death by John Webber and is therefore creating a “history painting of a history painting of a history painting”.9 Seen through a “black veil”, the “ghostly figures” take on a new dimension, like a new photographic archive which “challenge[s] a Eurocentric vision of colonial Australia”.10

Jason Wing and Michael Parekowhai : public monuments

While Boyd and Bennett have been ‘covering’ historical paintings, Jason Wing and Michael Parekhowai have fully reinterpreted the historical figure of Captain Cook through their sculptures. According to Wing, Australian history in school programs teaches that Cook discovered Australia in 1770. Knowing that Aborigines have the longest living culture on earth, it is nothing else than a “colonial lie”.11 But this belief is not specific to schools. It is also visible in the public space through numerous sculptures of Captain Cook which are scattered in the Australian landscape. In Hyde Park in Sydney, a huge bronze sculpture of Cook reads ‘Captain James Cook Discovered Australia 1770’ and personifies colonisation.

Jason Wing, Captain James Crook, 2013, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australie.

It is as a response to such sculptures that Jason Wing decided to create Captain James Crook (2013), his own monument to Cook. Wing states that “there are many politically correct terms [used to described the arrival of Cook in Australia] such as colonised, peacefully settled, occupied or discovered”.12 But for him “the truth is that Australia was stolen by armed robbery”.13 This choice of words is not harmless. Indeed, in his ‘new monument’, Wing represents Cook in a bronze bust over which has been put a balaclava, the epitome of the robber. By keeping the tradition of the bronze bust, Wing directly refers to a western tradition that he deliberately and provocatively criticizes and deconstructs. But Wing goes even further in the provocation as he discredits Cook’s name by changing into Crook. This paronomasia on the one hand and his sculpture on the other hand is a way for Wing to mark both Cook’s face and his name by the crimes he committed. Wing won the Parliament of NSW Aboriginal Art Prize in 2012 for a similar work named Australia Was Stolen by Armed Robbery. The irony of Wing winning the prize is that his own monument to Cook has been exhibited in Parliament alongside bronzes of other historical figures.

À gauche : Sir Nathaniel Dance-Holland, Portrait of James Cook, 1775,

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, Royaume Uni.

À droite : Michael Parekowhai, The English Channel, 2015, acier inoxidable,

257 x 166 x 158 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

If Wing’s creation can be regarded by some as confronting, Michael Parekowhai’s The English Channel (2015) seems, at first sight, rather elegant and almost glamorous. The larger-than-life sculpture is inspired by Nathaniel Dance’s famous Portrait of James Cook (1776). Cook is represented sitting on a worktable, as if he was “reflecting on his legacy in the contemporary world”, shining and reflecting in his silvery-mirror-like aspect.14 This surface which could be seen as a way to glorify the character, is in fact the reading key of the artwork. It is a way to “collect the reflection of everything around – including viewers looking at it”.15 In this way, the work needs to be experimented to gain full understanding. Indeed, depending on where the viewer stands, sits, or looks at, the perception and reflection shifts. This is a powerful mise en abyme of the way the vision and perception of history can shift. By engaging the viewer, Parekowhai wishes to invite him/her to reflect on and question Cook’s acts as well as the colonialism of Australia and New Zealand in particular, but also more broadly possibly the history of the British Empire.

After being exhibited in Brisbane as part of the Asia Pacific Triennial and Parekowhai’s installation The Promise Land, the gigantic sculpture has now found a home in Sydney. Exhibited in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Captain Cook is turned towards the window overlooking the harbour, a place that Captain Cook himself sailed past in 1770.

Christian Thomson, Michael Cook and Lisa Reihana : new technologies

Even if the use of painting and sculpture as traditional media has proven efficient to deconstruct the myth of colonisation, several contemporary artists have preferred the use of technology to enhance the discrepancy between past and present.

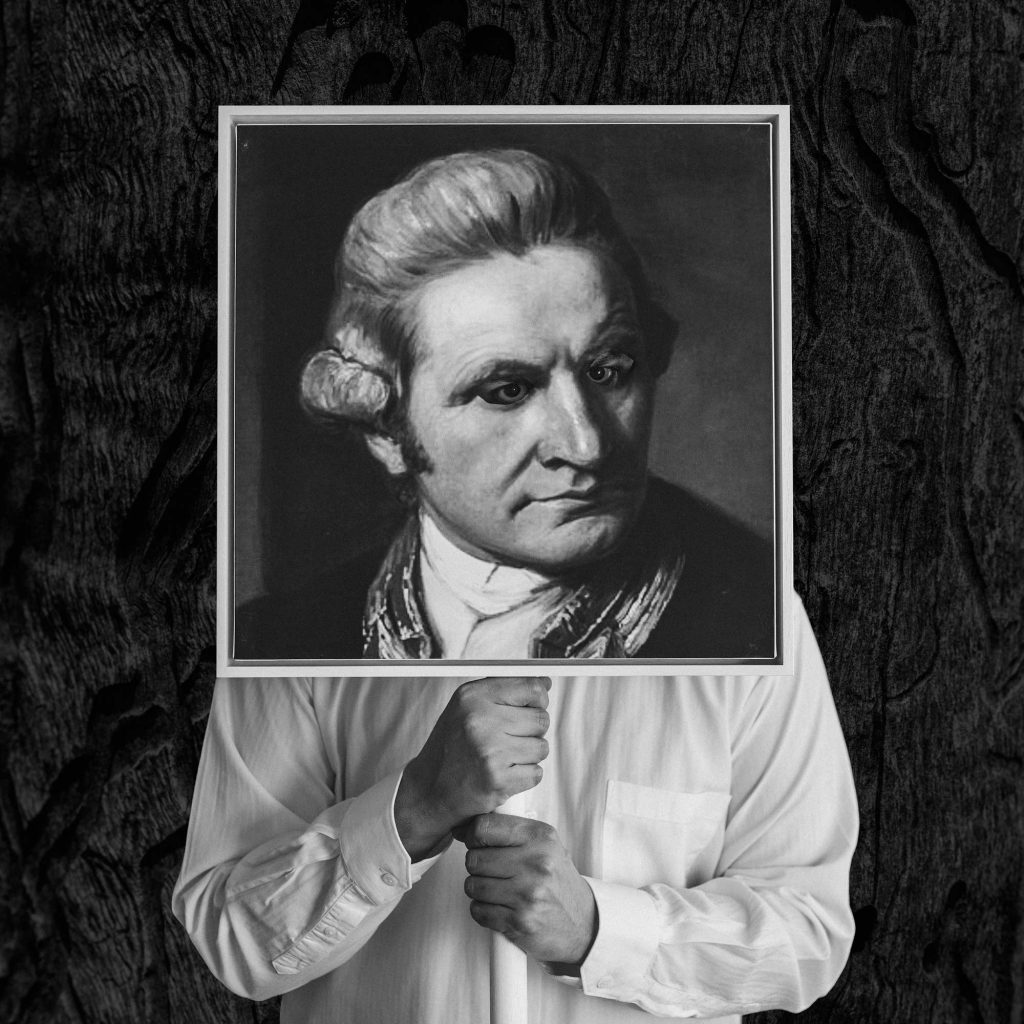

Christian Thompson, Museum of Others (Othering the Explorer, James Cook), 2016, impression c-type sur papier métallique,

120 x 120 cm, collection privée.

In his Museum of Others (Othering the Explorer, James Cook) (2016), Christian Thompson uses photography as part of an “auto-ethnographic practice”.16 While working at the Pitt-Rivers museum in Oxford, Thompson encountered several of the major figures of imperial invasion in photographic archives. To him, they were the essence of British Empire, of a white elite which colonised the land of his ancestors. In order to take possession of these figures and inverts history, he removed their eyes, therefore their power as Thompson argues.17 Thompson then looked through the holes from behind and captured the moment with his camera. Through this practice, he becomes an agent of history, one that has the power to look back on the acts of colonisation to direct a new gaze and create a new version of History. He becomes “The Eye of History”.18 Thanks to such creations, “historical collections can change to become both active and contemporary forces in the production of new cultural expression”.19 Christian Thompson shifts the role of photographic archive as collective colonial memory to places where decolonisation can happen under the governance of only one person who tries to make changes on historical past.

Michael Cook, Undiscovered, 2010, impression Inkjet, 124 x 100 cm, collection privée.

Where Thompson used archive to create his works, Michael Cook – a rather ironic name for an Indigenous Australian – created a dialogue around the ‘discovery’ of Australia through photographic utopian creations. In his series of photographs Undiscovered (2010), M. Cook plays with identities in an ethereal dream world, almost utopian, in order to provide a reflection, as if there was not such a thing as colonisation, by placing an Aboriginal man instead of Cook arriving on the shore of Australia. According to Bruce Mclean, this entire series could be seen as “Cook’s own modern Dreaming”.20 With this image, M. Cook creates a dialogue where the Aboriginal figure takes on the role of both the coloniser and the colonised.21 As in Gordon Bennett’s painting, black is neither absent nor erased from history anymore, but is present in M. Cook’s. With his works, M. Cook “question[s] the on-going perpetuation of these myths through popular Australian knowledge.”22 Indeed, once again, the viewer is the key element to how one will understand the work and what impact it will have on History and on popular Australian knowledge. James R. Ryan puts it in this way: “The power of these pictures is the reverse of what they seem. We may think we are going to them for knowledge about the past, but it is the knowledge we bring to them which makes them historically significant, transforming a more or less chance residue of the past into a precious icon”.23

Jean-Gabriel Charvet and Jean Dufour, Les Sauvages de la mer Pacifique, 1804, papier, gouache sur toile, 2020 x 1635mm (x2) 2020 x 1820mm (x1) 2200 x 1645mm (x1), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Lisa Reihana, in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015,

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Auckland, Nouvelle-Zélande.

This is this very same process of bringing knowledge to a historical object – wallpaper in this case – which has brought Lisa Reihana to create her video in Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015) for over a decade. In 1806, Jean-Gabriel Charvet created a panoramic wallpaper, Les Sauvages de la mer Pacifique, which was then printed by Joseph Dufour in the French town of Mâcon. It depicted a mythical view of what Europeans imagined the Pacific to be. It was largely inspired by the writings of Captain Cook and Jules Dumont d’Urville. Even if the description specified the different origins of the Indigenous people depicted, they all looked the same except for their outfits. The blackness of their skin was not taken in consideration at all in order to represent a mythical version of the Pacific islands. When Lisa Reihana discovered this wallpaper in the National Gallery of Australia, after being first amazed, she decided to respond to this work and subvert the European imperialist acts by restaging the whole story.24 Through her recreation, Reihana is “embark[ing] upon [… a] cultural endeavour of reclamation and imagining”.25 In her work, Reihana kept the background of the wallpaper which she animated, and then placed a re-enacted story played by different Indigenous people from the Pacific Islands acting on a green screen. For Reihana, giving the opportunity to Pacific Islanders to be a part of this project was a way to give them a place of resistance.26 Through her work, Reihana has made History visible, as a place you can visit over and over again.27 But her history is different to the one told in 19th century Europe. Indeed, one of the reasons why her work is <em[infected] is because of the presence of Europeans of course. But it is also [infected] because she introduced the violent scene of Captain Cook’s death at Kealakekua Bay as a place of rupture in the story. For Reihana, it is a way to investigate “visible ‘truths’”.28 These ‘truths’ are hiding, as in the previous artworks discussed, in this kind of in-between space, inside the veil created by the viewer’s gaze and reflection on the work. Thanks to contemporary technologies, Lisa Reihana has made in Pursuit of Venus [infected] the palimpsest29 of Les Sauvages de la mer Pacifique. More than this, in Pursuit of Venus [infected] can be read as a palimpsest of the history of colonisation in the Pacific Ocean, something essential to engage with decolonisation. In her work, Reihana has erased every single aspect of the white paradise that is visible in Les Sauvages de la mer Pacifique. The artist has only kept the environment in which the acts of colonisation happened by telling her own story of Cook’s arrival, disregarding what the past said about the glorious hours of Captain Cook in the Pacific.

“We will Not Forget

We Will Not Go Away

We Will Not Be Silent

We Will Not Die

WE WILL FIGHT

AND WE WILL SURVIVE

ABORIGINAL SOVEIREIGNTY

ALWAYS WAS ALWAYS WILL BE”30

These raging words written by Tina Baum, Australian Indigenous curator at the National Gallery of Australia, are a great way to voice the general feeling towards the oppression created by the “colonial lie”31 spread across Australia and the rest of the Pacific. If the “exploration and the settlement [were] a catalogue of intentions and accidents”, contemporary artists can be said to have become ethnographers, engaging with and defying decolonisation by researching the past through “The Eye of History”.32 Each of them, Gordon Bennett, Daniel Boyd, Jason Wing, Michael Parekowhai, Christian Thompson, Michael Cook and Lisa Reihana, have been challenging history in order to make all their works, palimpsests of the white, European, colonial history of the Pacific Ocean and its peoples. As in a palimpsest, the figure of Captain Cook has been erased. But although multiple layers have been superimposed, his figure is still perceptible. Undoubtedly, the palimpsest is an apt metaphor to represent and write history. The past cannot be erased, but new stories can be superimposed and created. If Captain Cook’s figure is the most recurring one in all the works we have discussed, it is indeed what Cook stands for as a whole which is subverted, criticized and contested.

Clémentine Débrosse

Image à la une : D’après Jacques de Loutherbourg et John Webber, The Apotheosis of Captain Cook, 20 Janvier 1794, gravure, 260 x 220 mm, Royal Academy of Arts, Londres, Royaume-Uni.

1 Short Oxford English Dictionary, p. 1881.

2 (Original : Defying Empire). Defying Empire était le titre de la troisième triennale nationale d’art indigène, l’exposition a eu lieu à la National Gallery d’Australie du 26 mai au 10 septembre 2017.

Defying Empire was the title of the 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial, exhibition happened at the National Gallery of Australia from 26 May to 10 September 2017.

3 BAUM In CROFT, B. L., 2009. Culture Warriors : Australian Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, p. 71.

4 BENNETT In FISHER, J. (ed.), 1994. Global Visions : Towards a new Internationalism in the Visual Arts. London, Kala Press in association with the Institute of International Visual Arts, p. 124.

5 BENNETT In FISHER, J. (ed.), 1994. Global Visions : Towards a new Internationalism in the Visual Arts. London, Kala Press in association with the Institute of International Visual Arts, p. 127.

6 MCLEAN, I. (dir.), 1996. The Art of Gordon Bennett. New South Wales, Craftsman House and G+B arts Int., p. 71.

7 MCLEAN, I. (dir.), 1996. The Art of Gordon Bennett. New South Wales, Craftsman House and G+B arts Int., p. 89.

8 BROWNING In BAUM, T., 2017. Defying Empire : 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, p. 34.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 MUNRO In BAUM, T., 2017. Defying Empire : 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, p. 129.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Art Gallery of New South Wales. « Michael Parekowhai – The English Channel ». [https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/432.2016/?tab=other], dernière consultation le 12 mai 2019

15 Ibid.

16 LEAHY, C. et RYAN, J. (eds.), 2018. Colony : Australia 1770-1861/Frontier Wars. Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, p. XVI.

17 Ibid.

18 RYAN, J. R., 1997. Picturing Empire : Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire. London, Reaktion, p. 16.

19 LEAHY, C. et RYAN, J. (eds.), 2018. Colony : Australia 1770-1861/Frontier Wars. Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, p. XVI.

20 Le « dreaming » ou temps du rêve est une mythologie liée à une personne et une entité qui peut être apparentée à un dieu.

In Aboriginal culture, a Dreaming is a mythology related to one person and one ‘godlike’ entity.

MCLEAN In LANE, C. et CUBILLO, F. (eds.), 2012. Undiscovered : 2nd National Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, p. 46.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 RYAN, J. R., 1997. Picturing Empire : Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire. London, Reaktion, p. 16.

24 DAVENPORT, In REIHANA, L. (ed.), 2015. Lisa Reihana : In Pursuit of Venus. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tāmaki, p. 6.

25 REIHANA, L. (ed.), 2015. Lisa Reihana : In Pursuit of Venus. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tāmaki. p. IX.

26 DAVENPORT, In REIHANA, L. (ed.), 2015. Lisa Reihana : In Pursuit of Venus. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tāmaki, p. 11.

27 VERCOE, In REIHANA, L. (ed.), 2015. Lisa Reihana : In Pursuit of Venus. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tāmaki, p. 60.

28 DAVENPORT, In REIHANA, L. (ed.), 2015. Lisa Reihana : In Pursuit of Venus. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tāmaki, p. 6.

29 Parchemin dont on a effacé la première écriture pour pouvoir écrire un nouveau texte.

A manuscript or piece of writing material on which later writing has been superimposed on effaced earlier writing.

30 BAUM, T., 2017. Defying Empire : 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, p. 19.

31 MUNRO, In BAUM, T., 2017. Defying Empire : 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, p. 129.

32 RYAN, J. R., 1997. Picturing Empire : Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire. London, Reaktion, p. 16.

Bibliography:

- Art Gallery of New South Wales. « Michael Parekowhai – The English Channel ». [https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/432.2016/?tab=other], dernière consultation le 12 mai 2019

- BAUM, T. (ed.), 2017. Defying Empire : 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia.

- BENNETT, G., 1993. « Aesthetics and Iconography : an Artist’s Approach ». In LÜTHI, B., et LEE, G. (ed.), Aratjara : Art of the First Australians : Traditional and Contemporary Works by Aboriginal and Strait Islander Artists. Köln, DuMont Buchverlag, pp. 85-91.

- BENNETT, G., 1994. « The Non-Sovereign Self (Diasporas Identities) ». In FISHER, J. (ed.), Global Visions : Towards a new Internationalism in the Visual Arts. London, Kala Press in association with the Institute of International Visual Arts, pp. 120-130.

- BERNADAC, A., 2017. « L’Affaire James Cook où Marshall Sahlins mène l’enquête ». In CASOAR. [https://casoar.org/2017/09/28/laffaire-james-cook-ou-marshall-sahlins-mene-lenquete/], dernière consultation le 12 mai 2019.

- BRUNT, P. et THOMAS, N. (eds.), 2018. Oceania. London, Royal Academy of Arts.

- CROFT, B. L., 2009. Culture Warriors : Australian Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia.

- DÉBROSSE, C., 2017. « Defying Empire : Troisième Triennale d’Art Indigène d’Australie et du Détroit de Torrès. » In CASOAR. [https://casoar.org/2017/09/04/ defying-empire-troisieme-triennale-dart-indigene-daustralie-et-du-detroit-de-torres/], dernière consultation le 12 mai 2019.

- FOSTER, H., 1994. « The Artist as Ethnographer ». In FISHER, J. (ed.), Global Visions : Towards a new Internationalism in the Visual Arts. London, Kala Press in association with the Institute of International Visual Arts, pp. 12-19.

- LANE, C. et CUBILLO, F. (eds.), 2012. Undiscovered : 2nd National Indigenous Art Triennial. Canberra, National Gallery of Australia.

- LEAHY, C. et RYAN, J. (eds.), 2018. Colony : Australia 1770-1861/Frontier Wars. Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria.

- MCLEAN, I. (dir.), 1996. The Art of Gordon Bennett. New South Wales, Craftsman House and G+B arts Int.

- Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art. « Michael Parekowhai – The Promised Land : Student Notes ». [https://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/15584/ Michael-Parekowhai-The-Promised-Land_Student_Worksheet.pdf], dernière consultation le 12 mai 2019.

- Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art. « Michael Parekowhai – The Promised Land : Teachers Notes ». [https://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/15586/ Michael-Parekowhai-The-Promised-Land_Teachers_Notes.pdf], dernière consultation le 12 mai 2019.

- REIHANA, L. (ed.), 2015. Lisa Reihana : In Pursuit of Venus. Auckland, Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tāmaki.

- RYAN, J. R., 1997. Picturing Empire : Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire. London, Reaktion.

- RYAN, J., 2016. « Lisa Reihana : In Pursuit of Venus ». In National Gallery of Victoria. [https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/lisa-reihana-in-pursuit-of-venus/], dernière consultation le 12 mai 2019.

2 Comments