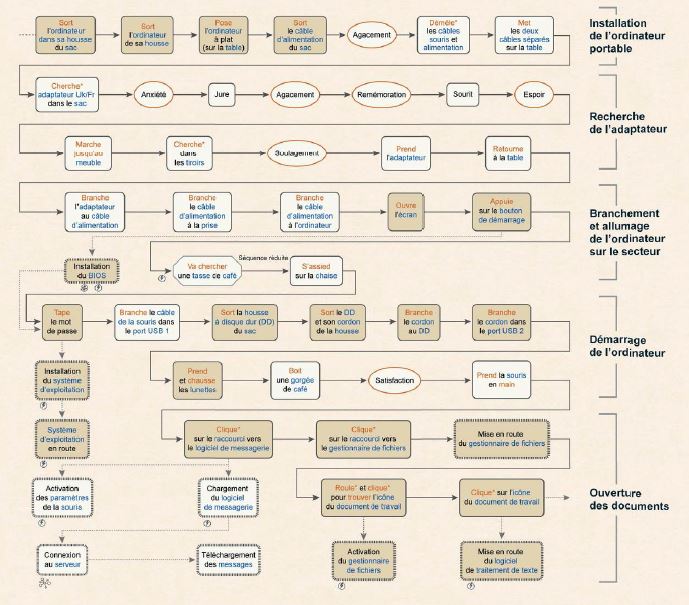

The anthropology of technology is a part of the science of the study of Man that is interested in the history and uses of technical facts as actions of Man on matter, which makes it a technology in the true sense of the term.1 It concerns, for example, the study of the means used and the process of felling a tree, but also much more contemporary problems such as the process of interaction of an individual with a computer during its operation.2 Interest in technological study has always existed within the discipline, and even in some of the travellers' accounts that precede its emergence, but it has not always been approached with the same stakes or interest.

The existing techniques within a society are primarily a classification criterion, which is linked to material culture for 19th century evolutionary anthropologists. The "industries "3 practised by societies (and of which the objects collected are the product) are means of distinguishing the "degree of evolution of a society" and are evoked by large and rather vague categories: stone cutting, ceramics, weaving, etc.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the recognition of the technical and artistic qualities of the material productions of many non-European societies, which had previously been discredited, encouraged ethnographers to better document the techniques of object creation and to reflect on their possible influences on society. Franz Boas, for example, links them to the types of forms and motifs produced.4 But they are still often secondary, and moreover, it is mainly the techniques for creating objects of exchange of wealth, magic or ceremonial that interest ethnographers5 and not those linked to the more 'trivial' aspects of life. The techniques are therefore often relegated to the background of monographs6, types of ethnographic studies whose ambitious desire to provide a general description of a given society cannot be free of certain shortcomings.

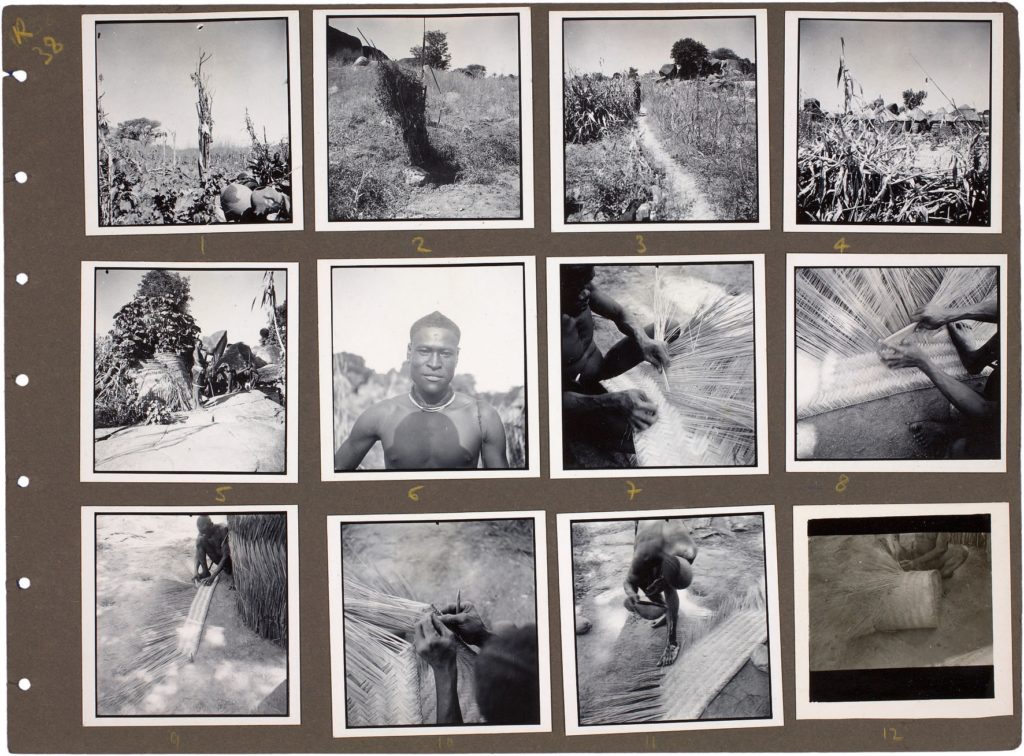

Basket making. Sao/Fali. Kotoko of North Cameroon, Chad and Nigeria Annie and Jean-Paul Lebeuf. Sahara Cameroon mission, 1936. © Lesc / Bibliothèque Éric-de-Dampierre in Buob, Dubois, « Manière de Noter », Techniques & Culture n°71, 2019.

Although Marcel Mauss (1872-1950) did not yet speak of an anthropology of techniques, some of his concepts paved the way. Firstly, the total social fact (fait social total), according to which any action or activity cannot be isolated from the society to which the individual performing it belongs, which implies that all techniques, even those that seem the most trivial, can provide information on the society studied. Secondly, the concept of the effective traditional act (acte traditionnel efficace) enlarges the field of study. Indeed, this notion implies, for example, that ritual acts have to be efficient, so there is a development of techniques to guarantee this efficiency. Thus a very large number of activities that do not aim to produce a material and tangible result (such as an object or a meal for example) are in fact concerned in a technological study.

This importance given to techniques was then deepened by André Leroi-Gourhan (1911-1986) whose work had a lasting impact on the French anthropological landscape when his main works on the subject were published in the middle of the 20th century.7 He developed, among other things, a method of analysing techniques with the ambition of systematically exploring techniques on a global scale. For him, it was possible to classify technical actions on such a large scale because they were part of trends (tendances), i.e. some of their aspects were inevitable and predictable because of the physical and chemical reality of the environment and of Man himself. For example, body adornment by ear piercing is a worldwide phenomenon because it is a visible location, without pain, without bloodshed, without major infectious risks and without particular bodily discomfort. These major trends are modulated by facts, which are those aspects of the techniques that are unpredictable, generally resulting from the particularities of the environment in which the social group evolves (the use of certain materials according to the resources available, for example) but which can also come from a borrowing from another society. He defines the fact as an unstable compromise between trends and the environment.

The research carried out by André Leroi-Gourhan, as well as his teaching work, were largely responsible for the emergence of cultural technology in France in the 1970s, led by researchers of the following generation such as Pierre Lemonnier, Hélène Balfet, Georges Haudricourt or Jean-Pierre Digard. This current insists on the importance of not detaching the technical fact from the other cultural productions of a society because "the study of a technical process constitutes a means [...] of relating technical phenomena to social phenomena "8 because they are in fact "social phenomena in their own right "9, socio-cultural phenomena even, whose means and goals often exceed its mere material efficiency. It is this assertion that the journal Techniques & Cultures, created in 1977 by this same generation of researchers, seeks to demonstrate through its issues, while also extending to other disciplines (history, economics, etc.).10

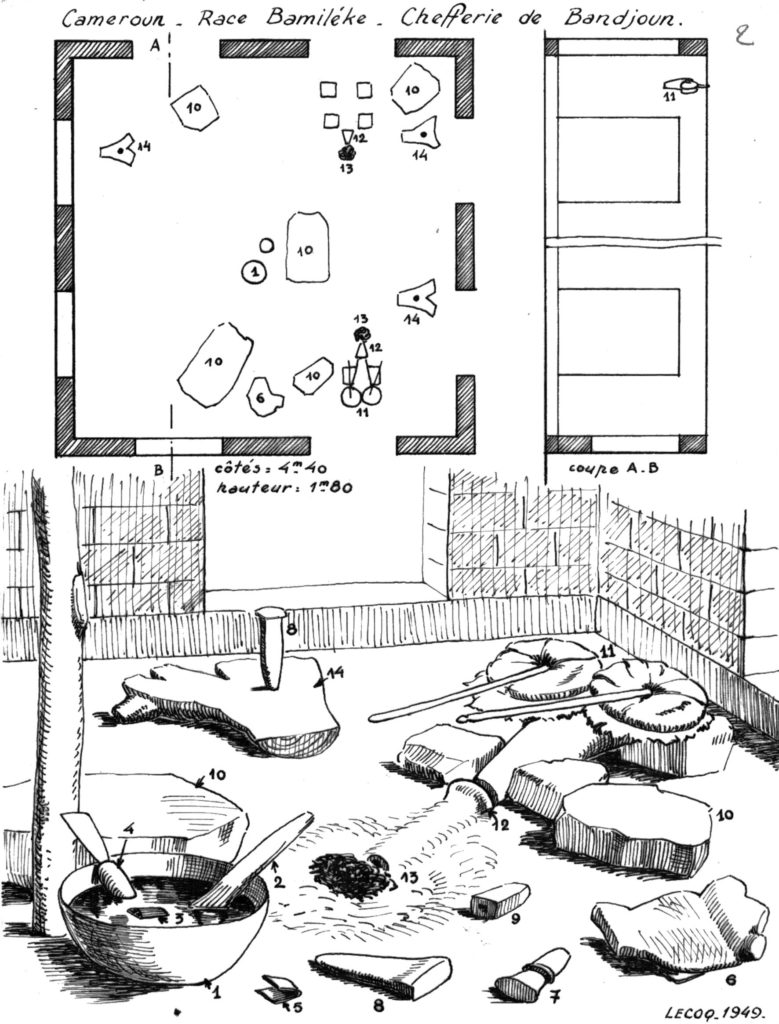

Forge. Bamiléke. Bandjoun, Cameroon Raymond Lecoq, 1949. Raymond Lecoq Fund © Lesc / Bibliothèque Éric-de-Dampierre in Buob, Dubois, « Manière de Noter », Techniques & Culture n°71, 2019.

Technology then becomes the focus of anthropological study, but it cannot stand alone, for it is its relationship with other aspects of society that allows anthropology to understand how it is a socio-cultural phenomenon and how it articulates its social environment. The study of the technical process thus goes beyond the simple description that would result from the researcher's observation, but instead engages him in a rather extensive informative research. Indeed, the list of the number of parameters involved in technical action is long, and the researcher cannot know in advance which ones will prove to be the most relevant for him. First of all, how can we define where a technical process begins (when raw materials are extracted, when tools are made), and where it ends (the creation of a finished product, its consumption, use or destruction)? But above all, what should be documented, and with what level of detail and on what scale? For example, simply in relation to the place where the activity takes place, we can be interested in its topography, its use during other temporalities, its owner(s), the reasons for its use, the possible possibilities of relocation and its positioning in relation to other places of activity11.

In order to be able to study these techniques more clearly, compare them and relate them to social phenomena in a readable way, it was necessary to develop methodological tools to document them effectively. One of these tools, the chaîne opératoire, was to become established without being clearly defined throughout the 20th century. After a certain period of uncertainty as to its precise meaning, the work of Hélène Baflet and the CNRS research group 748 (Technologie comparée, Matières et Manières), carried out in the 1980s, clarified its definition as the sole graphical representation of an observed technical process.12 It is the result of a posteriori analysis by the ethnographer who chooses precisely the information he wishes to restitute. Given the diversity of the technical processes observed, there is therefore great disparity from one chaîne opératoire to another, both in terms of content and form.

Graphical representation of the switch-on of a computer. © Ludovic Coupaye, 2017 in Techniques & Culture.

Today, as some regret, this tedious exercise is becoming less and less popular among anthropologists, despite the fact that it remains an obligatory passage for most students of the discipline. Faced with this loss of momentum, Lemonnier wants to reaffirm the importance of technical study and, above all, its relevance to understanding "systems of thought and social logics that cannot be identified and understood in any other way ".13 As he suggests, the new issues linked to the digital era could perhaps allow for a renewal of technological studies.

Morgane Martin

Cover image: Group of Fijians making sennit (magimagi) rolls, exchanged during Solevu, Cicia Island, Fiji, author and date unknown, © Cambridge Univeristy Museum of Archeology and Anthropology CUMAA

1 The current use of the term "technology" to designate certain techniques (digital, etc.) comes from an anglicism according to DIGARD, J.-P., 1979. « La technologie en anthropologie : fin de parcours ou nouveau souffle ? ». L’Homme, tome 19, n°1, p.74. Étymologiquement, tout comme l’antropo-logie est l’étude de l’Homme, la techno-logie est l’étude des techniques.

2 See the diagram for Turning on a computer by Coupaye.

3 In the sense of "All activities and operations whose purpose is the production and exchange of goods or the production of products intended to be used or consumed without first being sold". « Ensemble des activités, des opérations ayant pour objet la production et l’échange des marchandises ou la productions de produits destinés à êtres utilisés ou consommés sans être vendus au préalable ». CNRTL, « industrie », https://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/industrie, accessed on 08/01/2020.

4 BOAS, F., 2003 [1927]. L’art primitif. Paris, Adam Biro, p. 52.

5 Malinowski describes the technique of making kaloma (a small disc of shell), the assembly of which into a necklace forms a coin.In MALINOWSKI, B., 1963 [1922]. Les Argonautes du Pacifique occidental. Paris, Gallimard, p. 434.

6 DIGARD, J.-P., 1979. « La technologie en anthropologie : fin de parcours ou nouveau souffle ? ». L’Homme, tome 19, n°1, p.76

7 L’Homme et la Matière : Évolution et techniques en 1943, Milieu et Techniques en 1945 et Le Geste et la Parole en 1964.

8 LEMONNIER, P., 1983 « L’étude des systèmes techniques, une urgence en technologie culturelle ». Techniques & Culture, 1, p. 54.

9 LEMONNIER, P., 1983 « L’étude des systèmes techniques, une urgence en technologie culturelle ». Techniques & Culture, 1, p. 2.

10 Page « Présentation » de Techniques & Culture https://journals.openedition.org/tc/1553, dernière consultation le 07 janvier 2019.

11 BALFET, H., (ed.), 1991. Observer l’action techniques. Des chaînes opératoires, pour quoi faire ? Paris, éditions du CNRS, p. 12.

12 BALFET, H., (ed.), 1991. Observer l’action techniques. Des chaînes opératoires, pour quoi faire ? Paris, éditions du CNRS, p.14.

13 LEMONNIER, P., 2004. « Mythiques chaînes opératoires ». Techniques & Culture, p. 2.

Bibliography:

- BALFET, H., (ed.), 1991. Observer l’action techniques. Des chaînes opératoires, pour quoi faire ? Paris, éditions du CNRS.

- BOAS, F., 2003 [1927]. L’art primitif. Paris, Adam Biro.

- DIGARD, J.-P., 1979. « La technologie en anthropologie : fin de parcours ou nouveau souffle ? ». L’Homme, tome 19, n°1, pp. 73-104.

- LEMONNIER, P., 1983 « L’étude des systèmes techniques, une urgence en technologie culturelle ». Techniques & Culture, 1, pp. 11-34.

- LEMONNIER, P., 2004. « Mythiques chaînes opératoires ». Techniques & Culture, pp. 43-44.

- LEROI-GOURHAN, A., 1943. L’Homme et la Matière. Paris, Albin Michel.

- MALINOWSKI, B., 1963 [1922]. Les Argonautes du Pacifique occidental. Paris, Gallimard.

- Techniques & Culture 71, « Technographies », 2019 :

Fiches pratiques : Chaîne opératoire, p. 204, Points de vue et Finalités, p. 205, Échelles d’observation, p. 206, Protocole de collecte, p. 207, La chaîne opératoire comme représentation, p. 208.