*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

In last week’s article, CASOAR presented the exhibition À toi appartient le regard (…) et la liaison infinie entre les choses (musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac) which focuses on contemporary photography. We mentioned several artists who use their art as a platform to discuss the environmental changes caused by pollution and global warming. Today, we are having a look at some Pacific contemporary artworks that deal with these themes.

Let’s start with a video installation by the artist Taloi Havini (born in 1981, Nakas, Hakö) who comes from the autonomous region of Bougainville.1 Habitat (2016) shows a canoe going through the water of the old Australian copper mines of Panguna (Bougainville), and aerial images of this same landscape which is now abandoned. These mines were at the centre of a conflict which led to civil war (1988-1998).2 Their exploitation caused a significant amount of highly toxic pollution. In this artwork, Havini wants to show to the public the wounds of the landscape which are still open, but also the scars left by this exploitation left on the inhabitant’s daily life.

Habitat I, video installation, 3:43 minutes, Taloi Havini, 2016 © Taloi Havini

Bougainville is not the only place in Oceania where resources were and are still exploited at the expense of the environment and local populations. Think about nickel in New Caledonia/Kanaky, phosphate in Nauru, or coal in Australia. Mining can often be a cause of pollution as well as destruction of the land and marine environments. In her video Uncle Tasman – The Trembling Current that Scars the Earth (2008), Artist Natalie Robertson (born in 1962, Ngāti Porou and Clann Dhònnchaidh) shows her hometown, Kawerau (Aotearoa New-Zealand). More precisely, she films the hot springs there and the Tarawera river. Since 1954 and with the agreement of the government, a paper factory has been spilling its toxic waste in the river. Superimposed over these images are words, stories and facts told by the locals about this place, which contrasts with "the pollution [that] continues to contaminate the mauri, the vital force, of these rivers".3

Rivers, lakes, lagoons… When Westerners dream about Oceania, they often fantasize about a blue expanse of water. For them, the Pacific Ocean is nothing more than a body of water which separates the islands and the archipelagos from one another. On the contrary, Pacific Islanders consider the Ocean as a space where relationships are built and mythologies are told. It is a space which is crossed by roads used for travel, exchange and migrations.

One of the greatest problems in the Pacific Ocean, which is also the most publicized one, is plastic pollution. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is the name given to the seventh continent located in the North Pacific. The GPGP is a gyre created by the marine currents. It is composed of waste, most of them made of plastic (around 1,800 billion) – fishing nets, cans, bags and so on. Even though this « continent » has been known since the 1970s, it was only at its re-discovery in the 1990s by Captain Charles Moore, that we started to hear about it. As it is not a compact mass but scattered accumulations of waste, the GPGP is not visible in satellite images. This is not the only gyre on the planet. There are some in every ocean; there are two in the Pacific: one in the North and a smaller one in the South. As a result, numerous beaches are often littered with trash, mainly made out of plastic. Kamilo beach on the island of Hawai’i (Hawaii) is known to be covered by wastes coming from the ocean, which are pushed there by currents and winds. Artist Maika’i Tubbs (Honolulu, Hawaii) uses wastes found on the beaches of his native archipelago or in the streets of New York where he now lives and works. According to him, this trash has a liminal status: while it is made of waste it can also be considered like a treasure which is a potential source of creation. During the 2019 Honolulu Biennale, Tubbs exhibited his installation Toy Stories (2019) composed of white boxes reminiscent of the packaging used for children’s toys. One side of the sculptures shows a white shape which can be easily identified – a bird or a gun for instance – while the other side reveals the waste Tubbs used to create the objects. In A life of its Own (2013), he establishes a parallel between the Jericho rose, a non-endemic and invasive species that can be found on four Hawaiian islands, and plastic which is as invasive. Using white plastic tableware, which he heated and shaped, he reproduced this plant to cover the white walls where he created his installation. Like plastic – which pervades our daily life and at the same time is invisible to us – the Jericho rose that Tubbs created is hidden while it keeps on expanding at the same time.

Toy Stories, Maika'i Tubbs, plastic debris, 2019 © Maika'i Tubbs. Screen capture of Maika'i Tubbs' instagram account

A life of its Own, Maika'i Tubbs, installation, white plastic dishes, 2013 © Maika'i Tubbs.

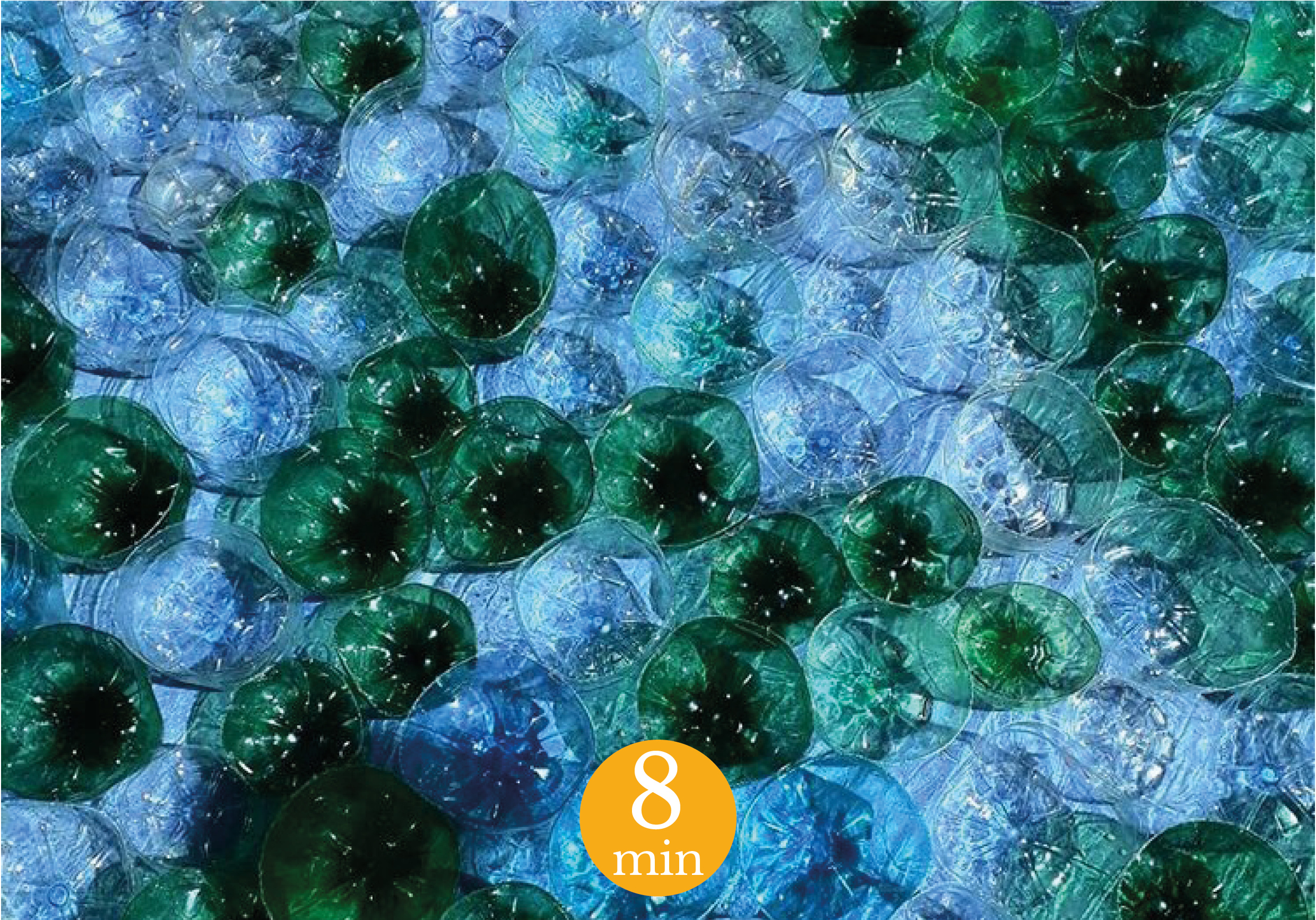

Tubbs is not the only artist who has found a new interest in plastic. George Nuku (born in 1964, Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Tuwharetoa) considers that it is the new pounamu. Pounamu is a stone, the nephrite, whose color goes from grey to green and that Māori find in the South Island of Aotearoa New-Zealand.4 It is a taonga for them, namely a cultural treasure. Pounamu is used to create ornaments like hei tiki5 pendants, and was sculpted to obtain weapons of prestige. According to Nuku, plastic and pounamu have the same qualities : transparency, solidity and brightness, among others (see the banner image). Thus, he thinks that plastic-pounamu is a sacred material, a taonga, like nephrite is. As a result, plastic pollution is itself sacred. This point of view is quite surprising for us living in a society obsessed by cleanliness and by the elimination of our waste. But it invites the public to re-evaluate this material and to enchant it again with art making.6

Bottled Ocean 2117, George Nuku, plexiglass,plastic bottles, paint, 2017, Kaohsiung City Museum of Fine Arts, Kaohsiung, Taïwan © George Nuku, photographs taken by Hung Long.

Illuminated by a green light in the middle of a marine atmosphere, Tangaroa, the god of the see, fishes and reptiles, is in mutation. It is surrounded by fishes, jellyfish and sharks in mutation because of their plastic environment.

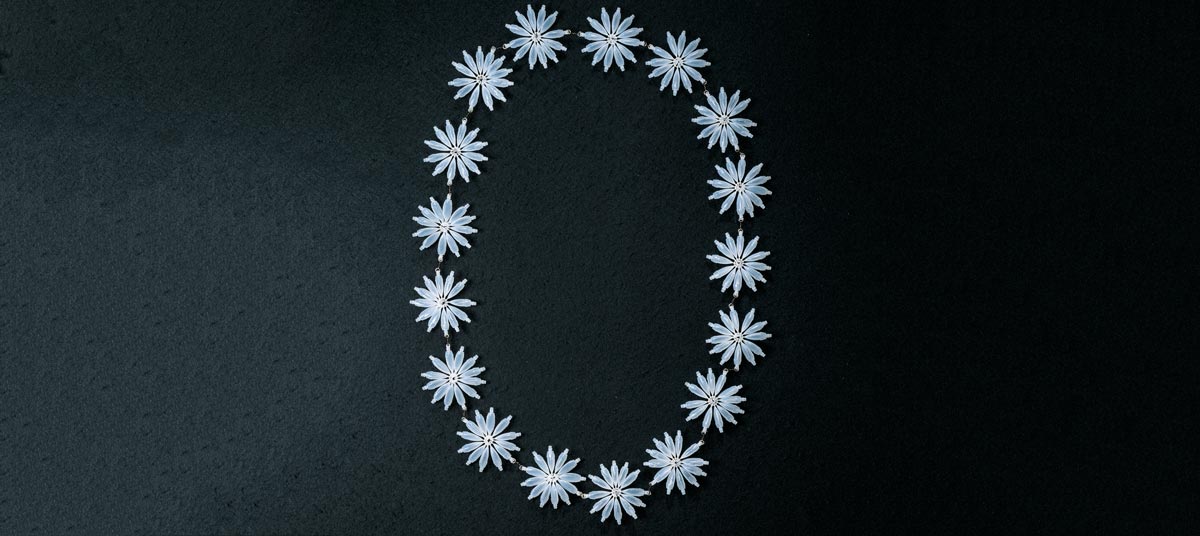

In her series Too much sushi (2002), Nikki Hastings-McFall (born in 1959, Samoa) creates lei flowers necklaces - where the flowers are replaced by small fish-shaped plastic capsules containing soy sauce used by restaurants. These lei play with one of the main symbols of Oceania, the flower necklaces that all tourists dream about… Through her work, Hastings-McFall reveals the pollution of the Pacific Ocean, the contamination of the waters and the marine species who swallow the plastic particles.7 However, fish is still a major resource in the daily diet of Oceanians. These awful particles go up the entire trophic chain, to the humans who also ingest them in many other ways. Here, we are really far from the idyllic vision of the tourist visiting Oceania, enchanted by the clean and blue waters, the lagoons and the palm trees…

Too much sushi II (Urban lei series), Nikki Hastings-McFall, soy sauce plastic containers, 2002 © Nikki Hastings-McFall.

Another crucial subject in Oceania is the question of rising sea level level. Islands are worried about this phenomenon. Though numerous documentaries have been created by Western people most of them showcase these islands as having no hope, as if they were already lost. The title of Christopher Horner’s documentary, The Disappearing of Tuvalu : Trouble in Paradise, (2004), speaks for itself. Yet, if we accept to look around and look for other voices, another point of view can be heard: one from a local perspective. In her artwork LICK (2013), Angela Tiatia (born in 1973, New-Zealand) is standing in the water clinging to a rock. During the whole performance, she tries to stay on this rock despite the movement of the waves. Gradually, she learns how to feel them and let herself be carried by the ocean. Tiatia wants to underlines the close-knit relationship between Pacific islanders’ bodies and the ocean and, in doing so, she suggests another way to consider the rising of seal level in Tuvalu.

LICK, Angela Tiatia, video work, 6:33 minutes, 2015 © Angela Tiatia/ Sullivant + Strumpf, Sydney and Singapour.

Speaking out about the effects of climate change and about pollution can be regarded as artistic oppositions to the prevailing discourses about these issues. Several artists, activists and academics who identify as indigenous insist on the fact that

not all humans are equally implicated in the forces that created the disasters driving contemporary human-environmental crises, and […] that not all humans are equally invited into the conceptual spaces where theses disasters are theorized or responses to disaster formulated.8

Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner (born in 1987, Republic of the Marshall Islands) and Joy Lehuanani Enomoto (Kanaka Maoli, Japanese, African American, Caddo, Pendjabi, Scottish) suggest that their installation Sounding (2020) be a place for Oceanians to meet and talk in order to find solutions to face climate change. This artwork was first created for the exhibition INUNDATION (Art Gallery, Hawai’i Mānoa University, Honolulu, 19th January - 28th February 2020), curated by Professor Jaimey Hamilton Faris (Hawai’i Mānoa University, Honolulu). Baskets which were weaved by Marshallese in Hawaii are hanging in a room with a maritime feel. On the floor in the centre of the room are a mat and another basket. Above, a probe is hanging from the ceiling and is similar to the ones used by the US Navy and scientists to measure the depth of the marine spaces. Finally, a whale is reproduced on a wall with printed reports of a probe. More than just a discussion space for Oceanians, this work is also pointing to a specific type of pollution we rarely think of: sound pollution. For instance, sonars of the US Marine prevent whales living near the Hawaiian coasts from hearing their food; it also disrupts their habits and habitat. The weaving of the baskets evokes the links between the generations of people, but also those between humans and the environment. This stresses the necessity to let concerned individuals express themselves about climate change. Weaved by Marshallese settled in Hawai’i, these baskets can also refer to the question of climate migration which affects a lot of archipelagos, like the Marshall Islands and the Kiribati, both in Micronesia. Some countries like Japan and the United Arab Emirates have offered to create artificial islands to remedy the problem.9 This project is metaphorically evoked with the baskets as, in Marshallese mythology, islands were created by the sand which fell off deity Letao’s baskets.

Sounding, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner et Joy Lehuanani Enomoto, installation with baskets, probe reports, probe lines, drawings, 2020 © Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and Joy Lehuanani Enomoto , Screen capture « Opening Artists Talks – Inundation 2020 »

Many inhabitants of Oceania, especially artists, speak out about climate change and its fallout. However, their voices seem to be considered only be considered rarely on the global scene. Some of them do manage to get their voices and messages through, like Kathy Jetn&il-Kijiner who was received as a civilian representative at the 2014 Summit for Climate organized by the United Nations in New York.10 Contemporary artworks can possibly be considered as a new way for people to get informed and for Oceanians to express their points of view. So, let’s open our eyes and listen…

Garance Nyssen

Cover image : detail of George Nuku's work made with bottom parts of plastic bottles during the Francofolies festival at the village Franc’Océan, La Rochelle, 13th and 14th july 2019 © George Nuku, photograph taken by Garance Nyssen

1 If some of you visited the exhibition Oceania (Royal Academy of Arts, London and musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, 2018 and 2019), you saw some of her works done with the photographer Stuart Miller. The pictures were from a series untitled Blood Generation (2009). Habitat II (2017) was exhibited from 14th June to 10th September 2017 at the Pavillon Neuflize OBC at the Palais de Tokyo (Paris), where the artist had her first solo exhibition in France.

2 This war opposed the Revolutionary Army of Bougainville (BRA), which wanted independence, to Papua New Guinea (PNG) which had been independent since 1975. Rapidly, a conflict also broke out between the BRA and some of Bougainville’s locals who were opposed to independence. Since the beginning of the 1970s, the Bougainville Copper Company exploited the Panguna copper mine, one of the biggest open sky mine in the world. As a consequence, the young independent nation of PNG thought it was in its economic interest to keep control over Bougainville. After the peace agreement of August 2001, it was decided that Bougainville would remain part of PNG, unless a referendum for independence wass organized before 2020. Regarding the mine, it never reopened after the war.

3 SMITH, H., 2011. Māori, leurs trésors ont une âme. Paris, Musée du quai Branly, Somogy, Editions d’art, p.168. Natalie Robertson's work is available on her website: https://natalierobertson.weebly.com/uncle-tasman—the-trembling-current-that-scars-the-earth.html#, consulted on 25th july 2020.

4 SPIGOLON, E., 29 novembre 2017, « Les eaux de jade d’Aotearoa », CASOAR, available at this URL: https://casoar.org/2017/11/29/les-eaux-de-jade-daotearoa/, consulted on 26th july 2020.

5 SPIGOLON, E., 28 novembre 2018, « Le Hei Tiki, porteur de mémoire », CASOAR, available at this URL: https://casoar.org/2018/11/28/le-hei-tiki-porteur-de-memoire/, consulted on 26th july 2020.

6 To know more about George Nuku's work with plastic-pounamuPounamu, you can read the following article: NYSSEN, G., 10 juillet 2019, « George Nuku : Message in a Bottle », CAOSAR, available at this URL: https://casoar.org/2019/07/10/george-nuku-message-in-a-bottle/, consulted on 26th july 2020.

7 To discover more about these works, you can go to the Te Papa Tongarewa museum (Wellington) website:

https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/531842, consulted on 26th july 2020.

8 TODD, Z. 2015. « Indigenizing the Anthropocene », In DAVIS, H., et TURPIN, E., éds. Art in the Anthropocene. Encounters Amongs Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, Londres, Open Humanities Press, p. 244.

9 OSBORNE, H., 20 février 2016, « Climate Change: Kiribati turns to artificial islands to save nation from Atlantis fate », International Business Times, available at this URL: https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/climate-change-kiribati-turns-artificial-islands-save-nation-atlantis-fate-1544942, consulted on 26th july 2020.

10 Global Call for Climate Action, 23 septembre 2014, « Marshallese poete Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner speaking at the UN Climate Leaders Summit in 2014 », available at this URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L4dxXo4thY, consulted on 26th july 2020.

Bibliography:

- Angela Tiatia, available at this URL: http://www.angelatiatia.com, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- Global Call for Climate Action, 23 septembre 2014, « Marshallese poete Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner speaking at the UN Climate Leaders Summit in 2014 », available at this URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L4dxXo4thY, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- Hawai’i Contemporary, « Honolulu Biennale 2019, Guide Book », available at this URL : https://hawaiicontemporary.org/hb19-guide-book, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- Joy Enomoto, available at this URL: https://www.joyenomoto.com/#, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- Maika’i Tubbs, available at this URL: http://www.maikaitubbs.com, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- Natalie Robertson, available at this URL: https://natalierobertson.weebly.com/uncle-tasman—the-trembling-current-that-scars-the-earth.html#, consulted on 25th july 2020.

- NYSSEN G., 10th july 2019. « George Nuku : Message in a Bottle », CASOAR, available at this URL: https://casoar.org/2019/07/10/george-nuku-message-in-a-bottle/, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- OSBORNE H., 20th february 2016. « Climate Change: Kiribati turns to artificial islands to save nation from Atlantis fate », International Business Times, available at this URL: https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/climate-change-kiribati-turns-artificial-islands-save-nation-atlantis-fate-1544942, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- SPIGOLON E., 28th november 2018, « Le Hei Tiki, porteur de mémoire », CASOAR, available at this URL: https://casoar.org/2018/11/28/le-hei-tiki-porteur-de-memoire/, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- SPIGOLON E., 29th november 2017, « Les eaux de jade d’Aotearoa », CASOAR, available at this URL: https://casoar.org/2017/11/29/les-eaux-de-jade-daotearoa/, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- Taloi Havini, available at this URL: https://www.taloihavini.com/, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- Te Papa Tongarewa, « Too much sushi lei », available at this URL: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/531842, consulted on 26th july 2020.

- TODD, Z. 2015. « Indigenizing the Anthropocene », In DAVIS, H., et TURPIN, E., éds. Art in the Anthropocene. Encounters Amongs Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, Londres, Open Humanities Press, pp. 241-254.