In 1901, the Commonwealth Restricted Immigration Act deprived the Queensland Kanaka Mission (QKM) of its raison d'être by prohibiting the use of foreign workers on Australian plantations. The missionaries were then faced with the question of what would happen to Christian converts once they returned to their archipelagos of origin. The situation in the Solomon Islands was of particular concern to them, as there was virtually no Christian presence in the archipelago at that time, and therefore no church to welcome the new Christians. So the QKM turned its attention from Australia to the Solomon Islands.

The mission built up a veritable mythology around its establishment in the Solomon Islands. According to Florence Young, the QKM decided to establish itself in the archipelago in 1904 in response to "cries for help" from converts who had recently returned home.1 It also changed its name to the South Sea Evangelical Mission (SSEM).

This is how the SSEM settled on the island of Malaita, which was particularly affected by blackbirding and from which many converts originated. Florence Young founded a school there at One Pusu, which was later to become the mission's headquarters in the archipelago. Gradually, its influence spread to the neighbouring islands of San Cristobal and Guadalcanal.

Map of the Solomon Islands. © CASOAR

To understand the conditions in which the mission was evolving, it is important to understand the situation in the Solomon Islands at the time. The archipelago had been a British protectorate since 1893, but the presence of the colonial government was minimal: only a handful of administrators were stationed there under the direction of Charles Morris Woodford, the Resident Commissionner. Their resources were very limited and their main objective was to put a stop to the headhunting practices that were present in the north of the archipelago and considered barbaric by Westerners. They periodically received support from the Royal Navy, which carried out punitive expeditions by cannonading the coastal villages in retaliation for the raids perpetrated against the white population of the archipelago. This population was also very small, less than a hundred individuals. It was mainly made up of merchants, a few planters and, of course, missionaries.2

The latter were not always in perfect agreement with the colonial government, but on the whole they relied heavily on each other. Conversion to Christianity guaranteed that the government would abandon the headhunting practices forbidden by the churches, and also that the converted populations would be brought together in villages, which were easier to administer. On the ground, certain missions also took over the government's educational and medical responsibilities by teaching English or setting up dispensaries.

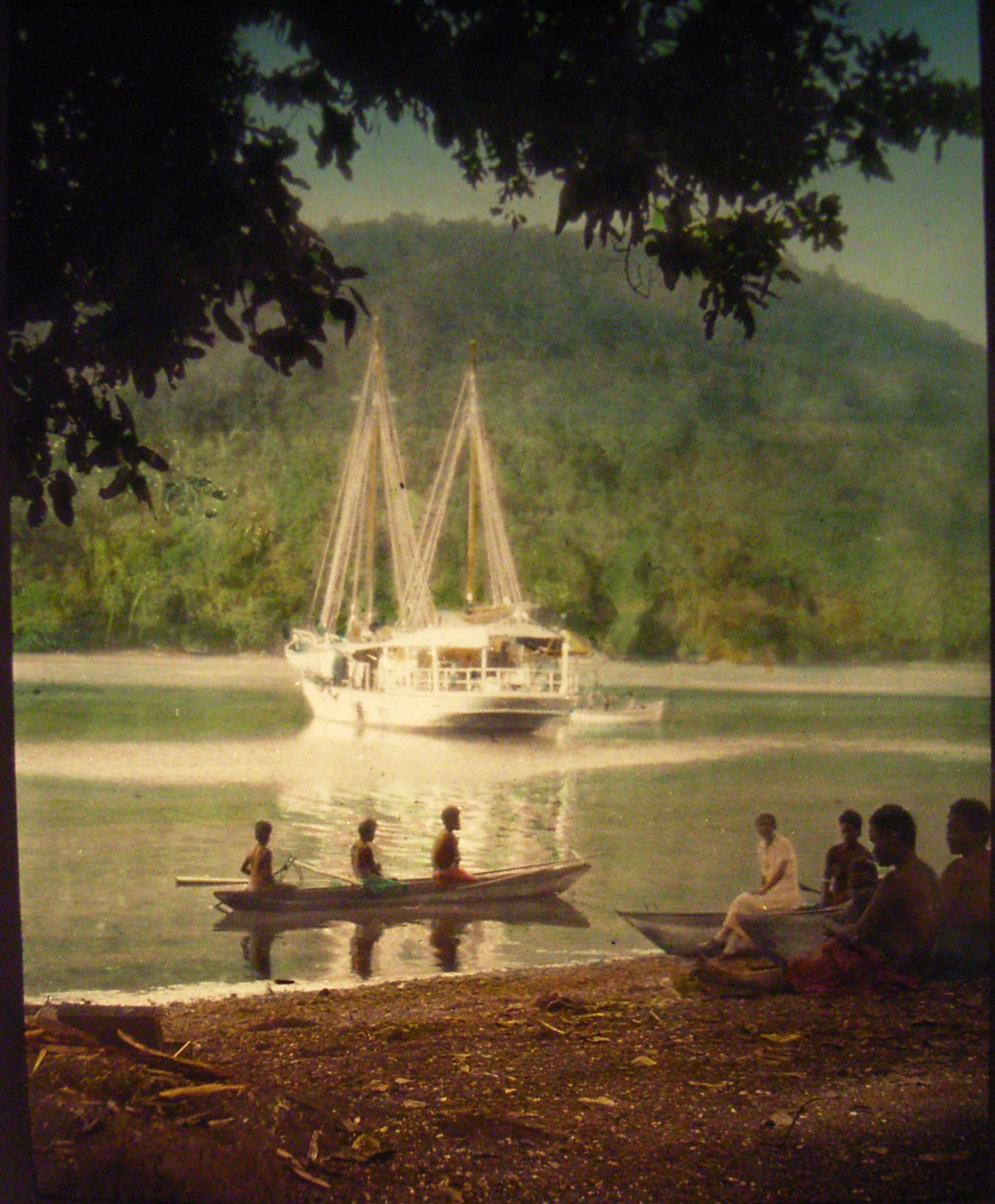

The Evangel in Makira.

These missionaries were usually few in number, not always very well equipped and suffered greatly from the difficult climate of the archipelago as well as from malaria. In 1914, the SSEM only consisted of 16 people, mainly based at One Pusu. It is worth noting that most of the mission's staff were women, in the image of its founder, who ran it with an iron fist. In spite of the times, Florence Young was a woman of strong character, who did not hesitate to spend half the year in the archipelago touring the converted populations on board the Evangel, the mission's steamer. She was sometimes accompanied by her nephew, Dr John Northcote Deck, who helped her in her endeavours. Historian David Hilliard describes Florence Young as "a striking example of that army of emancipated Victorian women who found an outlet for their fighting instincts in religious causes, preferably those in which they could assume a leadership position".3 Even today, the founder of the SSEM enjoys a very special respect among the members of this church, including the men who readily describe her as "a hero".4

Dr John Northcote Deck

But even Florence Young cannot hope to carry out evangelism alone. Like many other Christian missions, the SSEM relied on converted populations to supplement its Western staff. Rather than sending missionaries to settle in the villages, the SSEM sought out local men willing to spend time at the One Pusu school, where they received a rudimentary Christian education based on memorising lessons and learning the Pijin.5 These sessions lasted from a few weeks to a few months, and at the end of them, the new converts were sent back to their villages as teachers so that they, in turn, could convert their relatives.

These teachers lead the new congregations that have been founded and are visited several times a year by the Evangel, which provides them with some material, in particular Bibles and books on teaching Christianity. They are also responsible for applying the new rules laid down by the mission within their communities. The SSEM takes an extremely strict view of a number of practices. Anything perceived to be remotely linked to the old religion is rejected outright. Entities that were previously worshipped, whether deities, ancestors or more abstract spirits, are seen as envoys of the devil designed to deceive mankind. Warlike practices and headhunting were also condemned. Compared to other missions, the SSEM is also uncompromising on tattoos, "traditional" songs and dances, and the consumption of alcohol, tobacco or betel. These new rules, which were difficult to enforce in practice, were accompanied by a condescending and racist attitude on the part of the missionaries, who perceived the local populations as "almost animal-like".6 Violence, a tendency to lie and laziness were all blamed on them. This attitude may have led the people converted by the SSEM to reject their former religion and a number of cultural practices outright. The notion of ancestors, for example, which exists in many Pacific churches, was generally denied by SSEM Christians.7

The SSEC headquarters at One Pusu (Malaita).

However, we must not fall into the trap of considering the conversion of the populations of the Solomon Islands to Christianity as systematically imposed by force from outside. Although the missionaries were often allies of the colonial government, they themselves rarely had the means to exert physical coercion on the populations on whom they were often dependent. Moreover, the Solomon Islanders' interest in Christianity was certainly not solely motivated - at least initially - by religious considerations. In the context of Solomon Island societies, missionaries represented potential trading partners and a means of gaining access to coveted material goods. They also provided an opportunity to learn the Pijin language, which was spreading throughout the archipelago. Finally, as the churches became more established, they began to be perceived as political counter-powers and therefore as a means of social advancement and of challenging existing hierarchies.8 People whose prestige was already well established would convert in order to maintain it, while others would use conversion as a means of advancement. In particular, the status of teacher became particularly important and prestigious.

While it is difficult to completely unravel the reasons why men went to One Pusu and converted, it is important to try to address the issue. Reducing the history of conversion to an imposition by force is not only simplistic, but also completely disempowers the people of the Solomon Islands historically. Although the colonisation of the Solomon Islands was a profoundly unbalanced process of domination, the local populations were not content to stand by and do nothing. On the contrary, they engaged in a variety of interactions with the actors, whether through resistance, negotiation, collaboration or attempts to take advantage of the situation.

Nor should we give in to the bias of considering conversion as a 'bad' thing because it has led to what we perceive as an irreparable cultural loss, particularly within churches as intransigent as the SSEM. The SSEM succeeded in establishing a lasting presence in the Solomon Islands and in the 1960s changed its name once again to the South Sea Evangelical Church (SSEC), which is still one of the most important churches in the archipelago today. It was also at this time that a Solomon Islander was elected to head the church for the first time: Ganifiri, a native of Malaita and an important political leader. The SSEC thus became the first fully independent church in the archipelago and is now run entirely by Solomon Islanders.

Christianity is now fully integrated into the Solomon Islands and, paradoxical as it may seem to us, it has played an important role in the archipelago's demands for autonomy. Maasina Rule, a protest movement in Malaita in the 1950s, was deeply influenced by Christianity. Ganifiri was one of its leaders.9 Today, the people who are members of the SSEC do not see the conversion of their great-grandparents as a loss. On the contrary, it is seen as an extremely positive story, and those who played an active part in it, both missionaries and locals, are seen as role models, like Florence Young. So while there are cultural revival movements in some places that involve reappropriating certain practices banned by the missionaries, most of the time they are not seen as calling into question the Christian faith of those who participate in them.

Alice Bernadac

I want to deeply thank Paul Tetuha and his family who welcomed me in Lavagu during my fieldwork and gave me access to the photographs of the archives of the SSEC in Malaita. I also want to thank all SSEC members who accepted to talk with me about their history and their faith. ‘Aue !

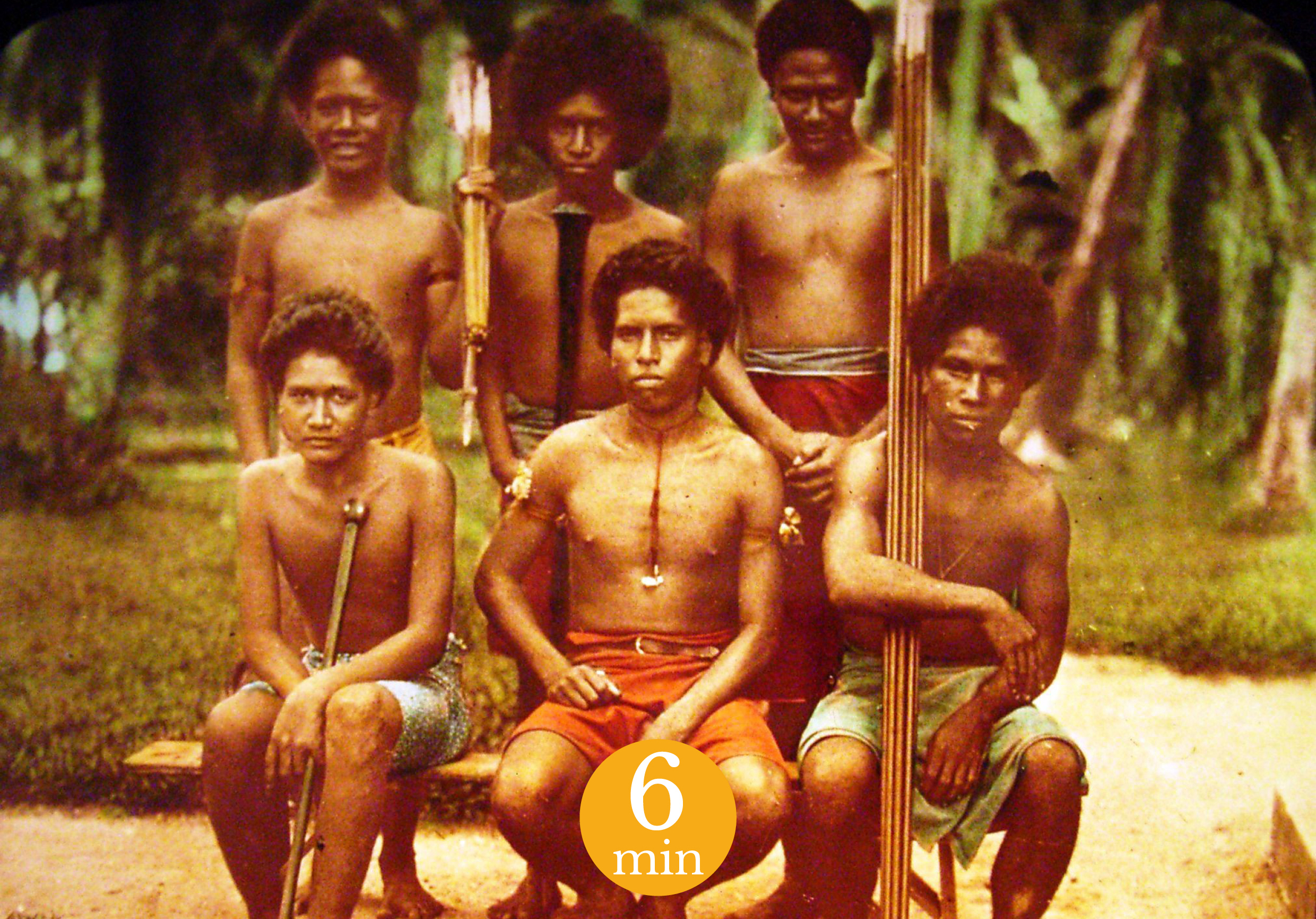

Cover picture: The first six converts from Rennell Island to One Pusu

1 YOUNG, F., 1925. Pearls from the Pacific. London, Edinburgh, Marshall Borthers, Ldt.

2 On the history of the Solomon Islands protectorate: The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. Canberra, ANU Press. As well as BENNETT, J., 1987. Wealth of the Solomons. A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978. Honolulu, Pacific Islands Studies Program, Center for Asian and Pacific Studies, University of Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press.

3 On these questions see: WILLAIME, J.-P., 1992. La Précarité Protestante. Sociologie du Protestantisme Contemporain. Genève, Labor et Fides.

4 HILLIARD, D., 1969. « The South Sea Evangelical Mission in the Solomon Islands. The

Foundation Years », The Journal of Pacific History. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, p. 42.

5 Data collected by the author in Rennell, village of Lavagu in October 2016 (See BERNADAC, A., 2017. Christianisme(s) à Renell (îles Salomon). Enjeux historiques et mobilisations contemporaines. Masters dissertation under the supervision of André Itéanu. Unpublished.

6 HILLIARD, D., 1969. « The South Sea Evangelical Mission in the Solomon Islands. The

Foundation Years », The Journal of Pacific History. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, p. 62.

7 HILLIARD, D., 1969. « The South Sea Evangelical Mission in the Solomon Islands. The

Foundation Years », The Journal of Pacific History. Melbourne, Oxford University Press,

pp. 41- 64.

8 BURT, B., 1993. Tradition and Christianity : the Colonial Transfomation of a Solomon IslandsSociety. Chur, Switzerland, Philadelphia, Hardwood Academic Publishers.

9 On the role played by Christianity in the Maasina Rule see BURT, B., 1993. Tradition and Christianity : the Colonial Transfomation of a Solomon IslandsSociety. Chur, Switzerland, Philadelphia, Hardwood Academic Publishers.

Bibliography:

- BARKER, J., 1990. Christianity in Oceania. Ethnographic Perspectives. Lanham, New York, University Press of America.

- BENNETT, J., 1987. Wealth of the Solomons. A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978. Honolulu, Pacific Islands Studies Program, Center for Asian and Pacific Studies, University of Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press.

- BURT, B., 1993. Tradition and Christianity : the Colonial Transfomation of a Solomon IslandsSociety. Chur, Switzerland, Philadelphia, Hardwood Academic Publishers.

- COLEMAN, S & HACKETT, R. (éds.), 2015. The Anthropology of Global Pentecotalism

and Evangelicalism. New York, New York University Press. - DECK, J.-N., 1945. South from Guadalcanal. The Romance of Rennell Island. Toronto,

Envangelical Publishers. - GRIFFITHS, A., 1977. Fire in the Islands ! The Act of the Holy Spirit in the Solomon. Wheaton,

Harold Shaw Publishers. - HILLIARD, D., 1969. « The South Sea Evangelical Mission in the Solomon Islands. The

Foundation Years », The Journal of Pacific History. Melbourne, Oxford University Press,

pp. 41- 64. - LAWRENCE, D., 2014. The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. Canberra, ANU Press.

- WILLAIME, J-P, 1992. La Précarité Protestante. Sociologie du Protestantisme Contemporain. Genève, Labor et Fides.

- YOUNG, F., 1925. Pearls from the Pacific. London, Edinburgh, Marshall Borthers, Ldt.