*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

Middle of the night. Large round eyes belonging to a head set on a surprisingly small neck stare at you, while a wide open prognate mouth is obviously about to start a conversation...

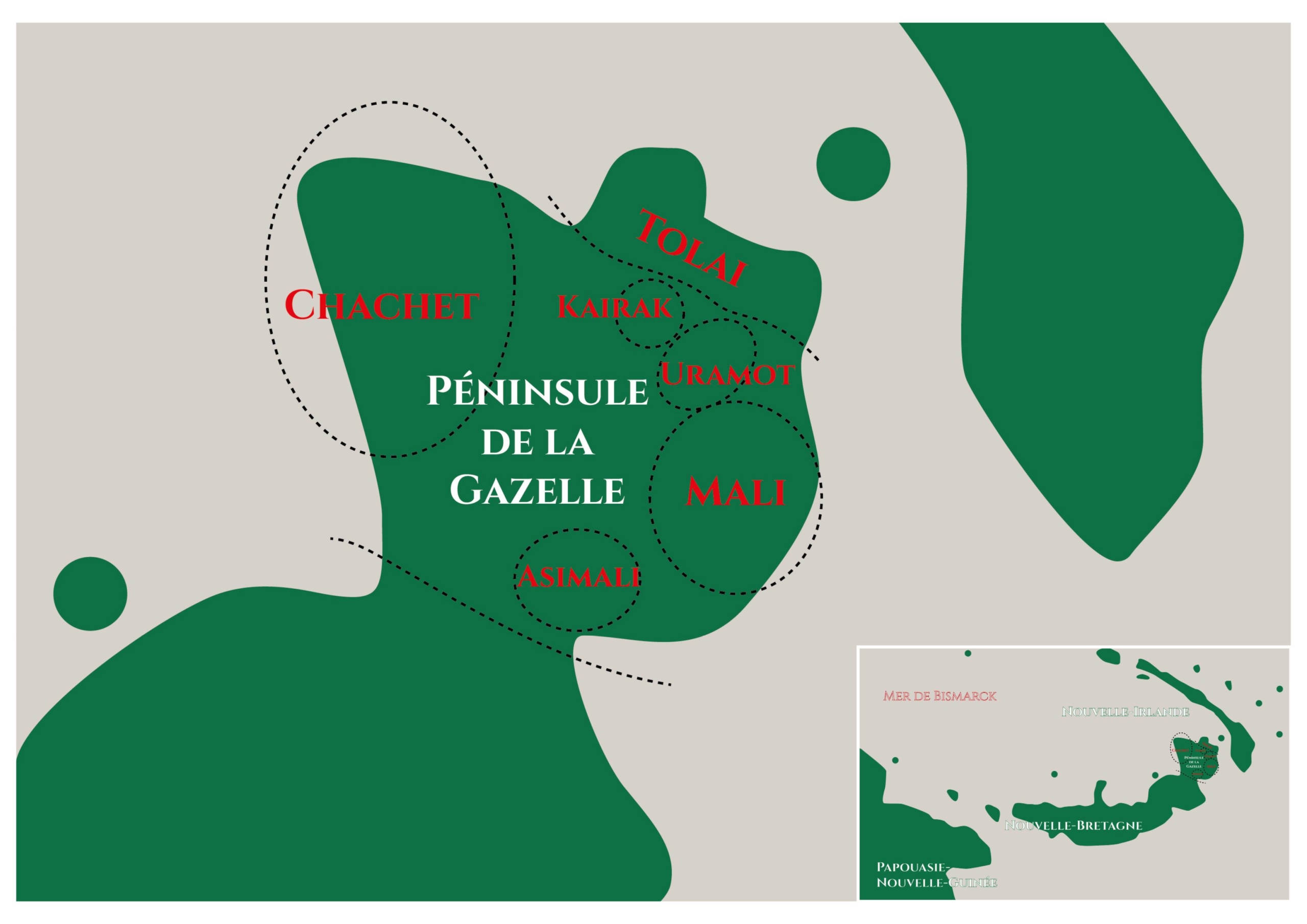

Don't panic! This isn’t an encounter of the third kind here, but just the very expressive kavat masks. kavat. These masks are made by a Papuan-speaking group known as the Baining, a name with an unflattering meaning ("wild people who live in the bush attributed by their neighbours, the Tolai people (Austronesian-speaking). They occupy with them the northern part of the island of New Britain (Papua New Guinea).1 Within the Bainingcultural group, several sub-groups can be distinguished; Chachet (or Qaqet) in the northwest, Asimbali in the south, Mali in the southeast, Kairak and Uramot (or Ura) in the centre.2 Although these linguistic groups are associated with geographical areas, this does not prevent a large circulation of these languages on the territory, within the framework of marriages or population movements.3 The name Kavat, which is the most common name for this type of bainingmask, come from the Kairak language.4 It is referred to by other names by the other sub-groups (kavet, atutki, tutki, atut, anguangi).5

Distribution of baining language groups, from Corbin, 1984, p. 44. © CASOAR

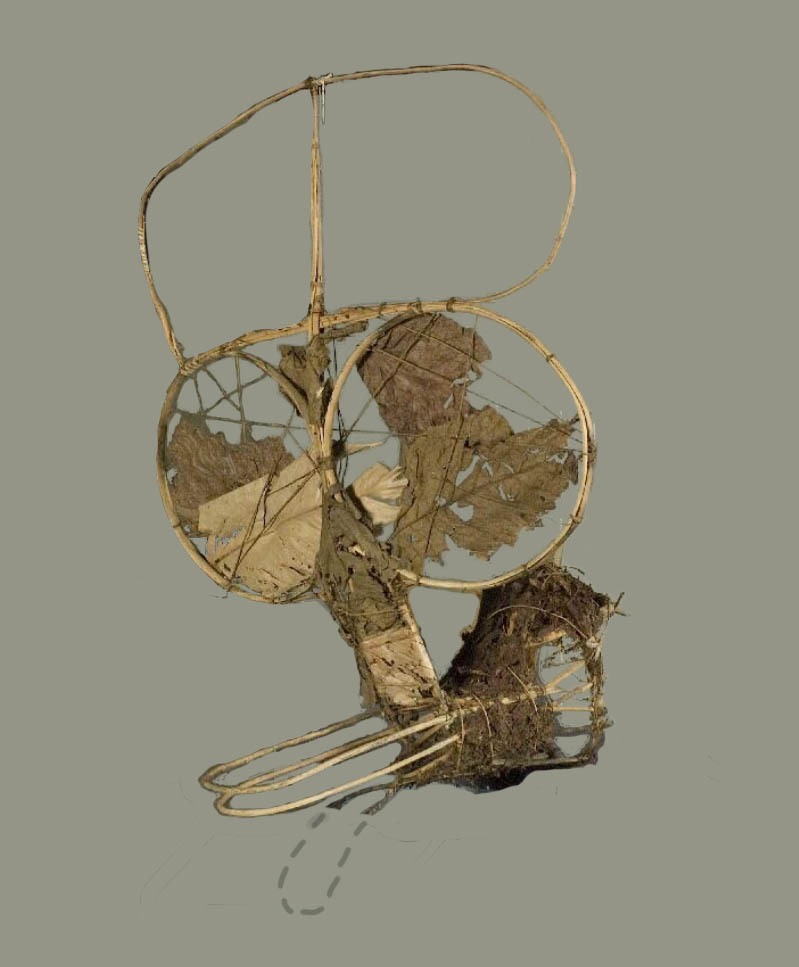

The kavat masks consist of a basic rattan structure forming several hoops tied together with plant fibres. This framework is completed by small sticks and a network of knotted plant fibres. This reinforces its stability and allows a layer of 'padding' leaves to be placed (which may not be present throughout the mask frame). A mask in the National Museum of Scotland shows that this layer can be made with printed paper.6 This method of manufacture makes it possible to obtain masks of good size while preserving a great lightness. All the manufacturing operations took place in a bush shelter, hidden from the rest of the community.7

Kavat mask where the tapa "skin" and part of the rattan structure are missing, from the Wereldmuseum. Photomontage by the author from a photograph of the object. © Collectie Wereldmuseum Rotterdam

On this skeleton is stretched the skin of thekavat, made of beaten bark (tapa). The tapa may come from different types of tree depending on the mask (paper mulberry, breadfruit, ficus) .8 Its production, from harvesting to beating, is a process carried out exclusively by men. It takes a lot of time to gather the quantity of tapa necessary to make all the masks that will be presented together, sometimes several dozen. It is stretched over the frame (probably still wet), being held together by sewing several tapa strips together to fit the shape, some of the ends of the strips are wedged into the frame. Ligatures made of plant fibres tie the tapa and some of the hoops together at several points to reinforce the cohesion between the two.

Baining mask being painted. © Lonely Planet

The mask can then be painted. The colours used for the designs are red, black and yellow (the latter colour being uncommon).9 According to Bateson10 and Corbin11, red is obtained from the seeds of the roucou (bixa orellana). It is also obtained from a mixture of saliva and blood that is "spit out" after cutting the tongue with a spiny leaf. Other methods of manufacture, always from plants, are also known. Currently, industrial materials are used to paint in this colour.12 Black is soot collected from leaves placed over a fire produced by burning coconut bark, into which sugar cane has been spat after chewing.13 Each of these colours is associated with sets of meanings. Red is linked to the idea of masculine; it is associated with flames, with the gushing of human and animal blood during wars and hunts, with saliva reddened by chewing betel nuts and with the spitting of blood on masks and headdresses. The colour black is linked to the feminine; it is associated with the ashes and soot of cooking fires, with earth and mud (and therefore with their fertility), with the dark and humid places where mythological spirits live, with the secretions of plants and trees. The colour white (the colour of tapa) is associated with the spirit world, which is associated with dampness; wet and very cloudy days, misty water holes. White is also associated with bones, semen and white lime (or clay) which is used to draw magical and protective patterns on the body.14

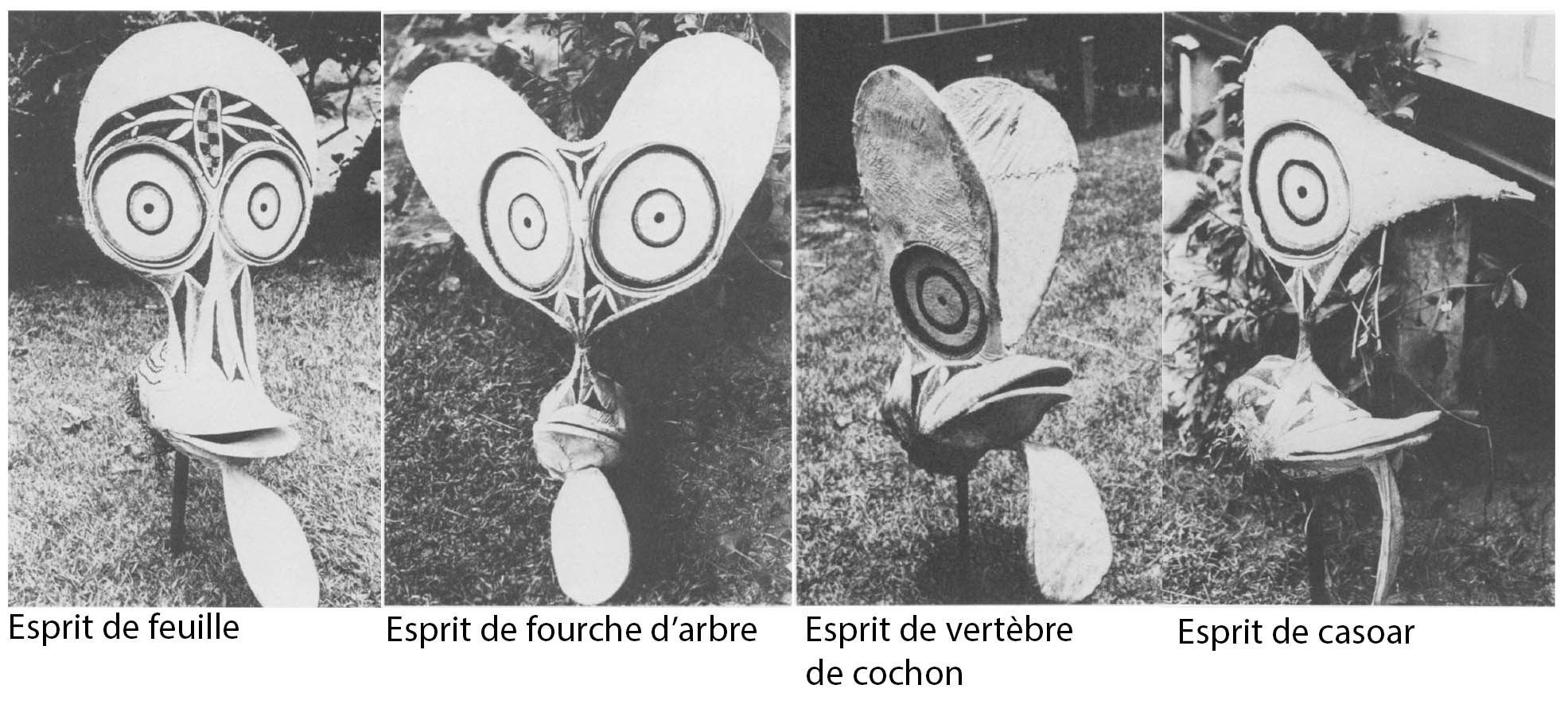

The geometric patterns painted on the tapa represent various elements of fauna and flora but also substances such as blood, sap, tears.15 The kavat mask evokes a particular type of spirit, identified by the general shape of the mask, which is generally found among the different sub-groups despite differing names and styles. Among the most common ancient forms in museum collections are the following types: leaf spirit (related to the large leaves used to wrap food and cover roofs) 16,tree fork spirit (related to support poles for dwellings, garden and bush sheds, and formerly the location where the dead were placed) 17, pig vertebra spirit and cassowary spirit.18 With the evolution of baining society during the 20th century, new types emerged; related to domestic animals or other miscellaneous elements (cow spirit, cat spirit, mosquito spirit, star spirit, ...).19

Differents kind of kavat mask (from left to right : Leaf spirit, Tree fork spirit, Pig vertebra spirit, Cassowary spirit). Pictures from CORBIN, 1984.

These masks are associated with the famous baining 'Fire Dance'. It was formerly called the Snake Dance because of the snakes that are brought by the dancers and given to the women who helped them feed during the preparations for the dance.20 This performance always takes place at night and is characterised by the dancing of masks around a fire to the rhythm of an all-male ensemble of musicians and singers. When the dance begins, the masks emerge one by one from the bush, each performing a short dance in front of the musicians before lining up on one side of the dance area until all the dancers have arrived.21 Three main types of headdresses and masks appear: red conical headdresses worn by the most inexperienced dancers (lignan), kavat masks and vungvung masks. The latter has the same shape than the kavat, but a bamboo "horn" is added to the front of the mask while a long piece of wood is placed at the back to balance it.

" Pungbung " [vungvung] mask. Uramat Baining. Photograph from Bateson ?, 1927-1928?, P.2937.ACH1. © Cambridge University Museum of Archeology and Anthropology.

The dancers' bodies are painted black and/or white according to the descriptions, and various plants are attached to the shoulders and mask as well as to the calves where they form a kind of leggings. They wear a particular penis case, made of tapa and shaped like a mushroom (which is circular when seen from the front), one end of which goes up towards the back through the crotch. This part used to be pinned to the skin at the bottom of the dancer's back, and then fell down to form a kind of 'tail'. Since at least the 1980s, it has been held by a string around the buttocks.22 During the night, each dancer wearing a kavat mask jumps and then runs through the fire, throwing ashes and even pieces of burning wood towards the other dancers and the audience.23 The dance is supposed to last until dawn, when the fire is finally extinguished by their trampling, and the masks return to the bush.24

Dancer wearing a lingan headdress. Drawing of Sarah Fabricant in CORBIN, FABRICANT, 1979, p.2.

The dancers wearing the kavat masks evoke the bush spirits, spirits that are reputed to be malicious and are sent home at the end of the performance. This highlights the ability of the initiated baining men to interact with the spirit world in the eyes of the community.25 However, the conditions for the holding of a Fire Dance have long remained uncertain for ethnologists, who first associated it with fertility cycles linked to the harvest, coordinated with initiation rites, mourning and weddings. Fajans, for her part, hypothesises that this dance is not linked to a particular cycle.26 It is a time when normal social distinctions are broken down: the bush spirits, supernatural entities, invade the central square.27 Humans 'metamorphose', and their dancing is chaotic compared to other types of dances. As a reward for this disruption of the social order, a moment of privileged interaction with the supernatural was created, which allows the baining to recover some of the power of these spirits to their advantage.28

At present, this Fire Dance is performed on various events within the community: school or shop openings, bereavements, weddings, initiations, etc29 However, the baining Fire Dance is above all a true cultural phenomenon that has made the Baining people famous at regional and international level. It is a real tourist phenomenon and an essential part of the trips organised by travel agencies in New Britain. It is also one of the most anticipated performances at various regional cultural festivals such as the National Mask Festival (New Britain) or national festivals such as the Melanesian Festival of Arts and Culture (Port Moresby, 2014). This popularity provides the baining with a significant source of income through organised performances for tourists. It also allows this community to assert itself politically and has been used as a means of pressure to gain respect from their Tolai neighbours. 30 . This performance is now one of the central points of their cultural identity and kastom. In doing so, the emulation between the different baining community groups to achieve the best Fire Dance ensures the continuity of the knowledge of kavat mask making. It also leaves room for innovation to create the most beautiful masks possible, which promises new types of kavat to discover!

Morgane Martin

Main Image : Baining Fire Dancer, 2008 © Taro Taylor

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bainingsfiredancer.jpg

1 HERMANN, I., 2001. « Baining Art” in Form Coulour Inspiration : Oceanic Art from New Britain, Stuttgart : Arnoldsche, p. 78.

2 CORBIN, G., 1984. « The Central Baining Revisited : “Salvage” Art History among the Baining of East New Britain, Papua New Guinea”, RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics n°7/8, p. 44, p.46.

3 FAIK-SIMET, N., 2017. « The Politics of the Baining Fire Dance” in A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes, Canberra : ANU press, p.252.

4 CORBIN, G., 1976. “The art of the Baining or New Britain”, Ann Arbor, Michigan, University Microfilms (Thesis defended in 1976 at Columbia University), p.93.

5 FAIK-SIMET, 2017, p. 256.

6 YANEVA-TORAMAN, I., 2014. “Barkcloth and the Baining : Masks in New Britain” [online], accessed on 09/02/2021.

URL : https://pacificcollectionsreview.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/barkcloth-and-the-baining-masks-in-new-britain

7 CORBIN, G., FABRICANT, S., 1979. « Some notes on Kairak Baining night dance headdresses and masks”, Pacific Arts Newsletter n°9, p.5.

8 HILL, R. 2001. “Traditional Barkcloth from Papua New Guinea”, Barkcloth : Aspect of Preservation, Use, Deterioration, Conservation and Display, Margot M. Wright (ed.), London : Archetype publication, p.30.

9 HERMANN, 2001, p.83.

10 BATESON, G., 1932. « Further notes on a snake dance of the baining”, Oceania, vol. 2, n°3, p.335.

11 CORBIN, 1976, p.93.

12 HERMANN, 2001, p.83.

13 Ibid., p.93.

14 CORBIN, 1984, pp.46-47.

15 Ibid., p.47.

16 Ibid., p. 47.

17 Ibid., p.49.

18 Ibid., p.50.

9 Ibid., p.67.

20Ibid., p.47.

21 CORBIN, 1976, p.94.

22 FAJANS, J, 1985. They make themselves : live cycle, domestic cycle and ritual amond the baining (vol. I and II), Ann Arbor, Michigan, University Microfilms (Thesis defended in 1985 at Stanford University), p.440.

23 Ibid., p.458.

24 CORBIN, 1976, p.95. However, Fajans did not observe this practice during her fieldwork (FAJANS, 1985, p.460).

25 FAIK-SIMET, 2017, p.255.

26 Ibid., p.254.

27 FAJANS, 1985, p.464.

28 Ibid., p.466.

29 FAIK-SIMET, 2017, p.257. This would confirm Fajan's hypothesis.

30 Ibid., p.263.

Bibliography:

- BATESON, G., 1932. « Further notes on a snake dance of the baining”, Oceania, vol.2, n°3, p.334-341.

- CORBIN, G., 1976. “The art of the Baining or New Britain”, Ann Arbor, Michigan, University Microfilms (Thesis defended in 1976 at Columbia University), p.93.

- CORBIN, G., 1984. « The Central Baining Revisited : “Salvage” Art History among the Baining of East New Britain, Papua New Guinea”, RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics n°7/8, pp. 44-69.

- CORBIN, G., FABRICANT, S., 1979. « Some notes on Kairak Baining night dance headdresses and masks”, Pacific Arts Newsletter n°9, pp. 2-5.

- FAIK-SIMET, N., 2017. « The Politics of the Baining Fire Dance” in A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes, Canberra : ANU press, pp. 251-266.

- FAJANS, J, 1985. They make themselves : live cycle, domestic cycle and ritual amond the baining (vol. I and II), Ann Arbor, Michigan, University Microfilms (Thesis defended in 1985 at Stanford University), p.440.

- HERMANN, I., 2001. « Baining Art” in Form Coulour Inspiration : Oceanic Art from New Britain, Stuttgart : Arnoldsche, pp. 79-84.

- HILL, R., 2001. “Traditional Barkcloth from Papua New Guinea”, Barkcloth : Aspect of Preservation, Use, Deterioration, Conservation and Display, Margot M. Wright (ed.), London : Archetype publication, pp. 24-65.

- YANEVA-TORAMAN, I., 2014. “Barkcloth and the Baining : Masks in New Britain” [online], accessed on 09/02/2021.

URL : https://pacificcollectionsreview.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/barkcloth-and-the-baining-masks-in-new-britain