*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

The Hawaiian archipelago is generally known for its feather objets: ahu‘ula, cloaks; mahiole, helmets; kāhili, fly-flaps; lei, necklaces, etc. In this article, CASOAR chooses to introduce you to only one of them: kāhili, which can be found in many museums across the world as well as in Hawaii, in the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum which preserves 250 of them.1

Kāhili held in the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum collections, red feathers, turtle shell, shell, ivory, ribbon, 129,5 x 15,2 cm and 107,5 x 16 cm, 19th century, 10245/1910.008 et 00090 © CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 216.

In theHawaiian Dictionary written by Mary Kawena Pukui and Samuel H. Elbert, kāhili is defined as: « feather standard, symbol of royalty… to brush, sweep, switch ».2 Insignia of authority, these objects are often called fly-flaps in Polynesia. In this cultural area, their shapes and materials can be different. Those from Hawaii are, for the older ones, made from wood, turtle scale, bone, ivory and mostly yellow, red, black and white feathers. Just like ‘ahu‘ula (cloaks) and mahiole (helmets), kāhili were named and for the most recent ones, their name was written on their pole.3 If the names of numerous kāhili were not transmitted, several have crossed the time like for some of Queen Emma Kaleleonālani Rooke (1836-1885), wife of Kamehameha IV). For instance, one of her kāhili 's name is Lā‘ielohelohe, taken from one of her ancestors.

The kāhili are composed of different parts:

- thehulumanu, a cylinder made from many ‘au(branches);

- the kumuthe wood pole where, in the upper part, the branches are attached, the rest being the gripping part;

- the pā‘ū, , the skirt, linking-up thehulumanu and the kumu.

While mostly of cylinder shape, thehulumanu can have other appearances. Its ‘au (branches) are generally made out of ‘ie‘ie, (pandanus) or of coconut palm ribs. The stems are often separated in several sprigs in order to have four or eight growths were one can attach the feather bundles. Depending on the amount of growths, the result can be quite or not so luxuriant. Indeed, there can be hundreds of feathers in only one kāhili. It was also possible to create the ‘au (branches) from preexisting units. Roger G. Rose, Sheila Conant and Eric P. Kjellgren think that this second technique was used when a kāhili was created from older ones.4 Theolonā fibre (Touchardia latifolia) was employed to fix the ‘au (branches) to the kumu (pole). Later, it was replaced by cotton. kumu (pole) could have been the most important part of the kāhili as its name came from it. Various materials could be used to make it: an old spear, a piece or an assemblage of woods or a piece of wood alternatively covered by turtle scale discs and tubular pieces of whale ivory or bones like in one of the examples preserved by the British Museum Oc,HAW.167. The bone we can see on it is Kaneoneo’s tibia, a chief from the island of Kauai. He fought against Kamehameha Ist on the island of Hawai’i because the latter wanted to extend his power on Kauai. The bones used were from the legs or the arms, « one of the traditional residing places of a person’s mana or spirituel power ».5 In Hawaii, bones could be preserved as relics and were safely hidden or they were put in an object to either humiliate or honor someone.6 Finally, the pā‘ū (jupe) était réalisée dans plusieurs types de matériaux : un kapa beaten bark cloth), a textile, a net made from vegetal fibers, etc.7 It could be covered of feathers, like in the example from the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac [MQB-JC] or it could be left as it was, like on recent kāhili . In this one from the MQB-JC, a turtle scale disk serves to keep it in place and on others, kapa could do the job too. On the most recent examples, a ribbon was put under the pā’ū (skirt), on the kumu (pole). The various components of a kāhili could be dismantled and stored which allowed, later, to create other kāhili .

Kāhili, frigate feathers split in their length, nae (net) made from olonā fibres, yellow and red feathers, wood, whale ivory, turtle scale, kapa, vegetal fibres, 212 x 23 x 20, musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, 72.53.281.

In Polynesia, birds and their feathers were beings and materials of great importance because they were linked to divinities. In Hawaii for instance, the goddess Lā‘ieikawai had a house covered in feathers. The divinities’ bodies were also covered in feathers and the birds themselves, in the world of the livings, were often considered as signs of the presence of the divine. Thus, « through feather adornment, the mana of the gods was extended to the chiefs » 8, the red and yellow colors being principally reserved for them. Feathers used in Kānaka maoli objects came from different birds, indigenous, endemic or imported. The ‘i‘iwi were used for their red feathers, like the ‘apapane, whose feathers were of a deeper red. The ‘ō‘ō was captured for its yellow feathers, like the mamo, and for their black ones too.9 Sources disagree on what happened to the birds after this process: were they captured in order to take off few feathers and then released, or were the captured and killed for their flesh to be eaten? However, it is clear that only a specific category of people was devoted to this task: the kia manu.10

If it seems that ‘ahu‘ula (cloaks) and mahiole (helmets), were initially only worn by male chiefs and also made by men, lei, (necklaces) and kāhili could be used and made by women chiefs and of high-ranks.11

At the time of the first contacts with the Europeans, it appears that kāhili were of small sizes and held in hand, like the other fly-flaps in the rest of Polynesia (tahiri in Tahiti, tahi‘i in the Marquesas islands, tāwhiri in Aotearoa - New Zealand, etc.).12 They were called kāhili lele or kāhili pa‘a lima. « Although [they] provided practical benefits of personal cooling […], they served primarily to mark the presence and spiritually protect an important individual of ali‘i or chiefly rank ».13 In the 19thth century, the kāhili ku were the most developed model. They were of bigger sizes (between two and five meters) and could stand on a foot. At this time, the kāhili restent toutefois toujours des objets qui accompagnent les femmes et hommes de haut rang. Un intendant les suivait constamment, agitant le kāhili au-dessus de la tête de leurs chef·fe·s, l’une des parties la plus sacrée de leur corps. Celleux qui portaient ces objets étaient appelé·e·s les pa‘a kāhili or lawe kāhili.

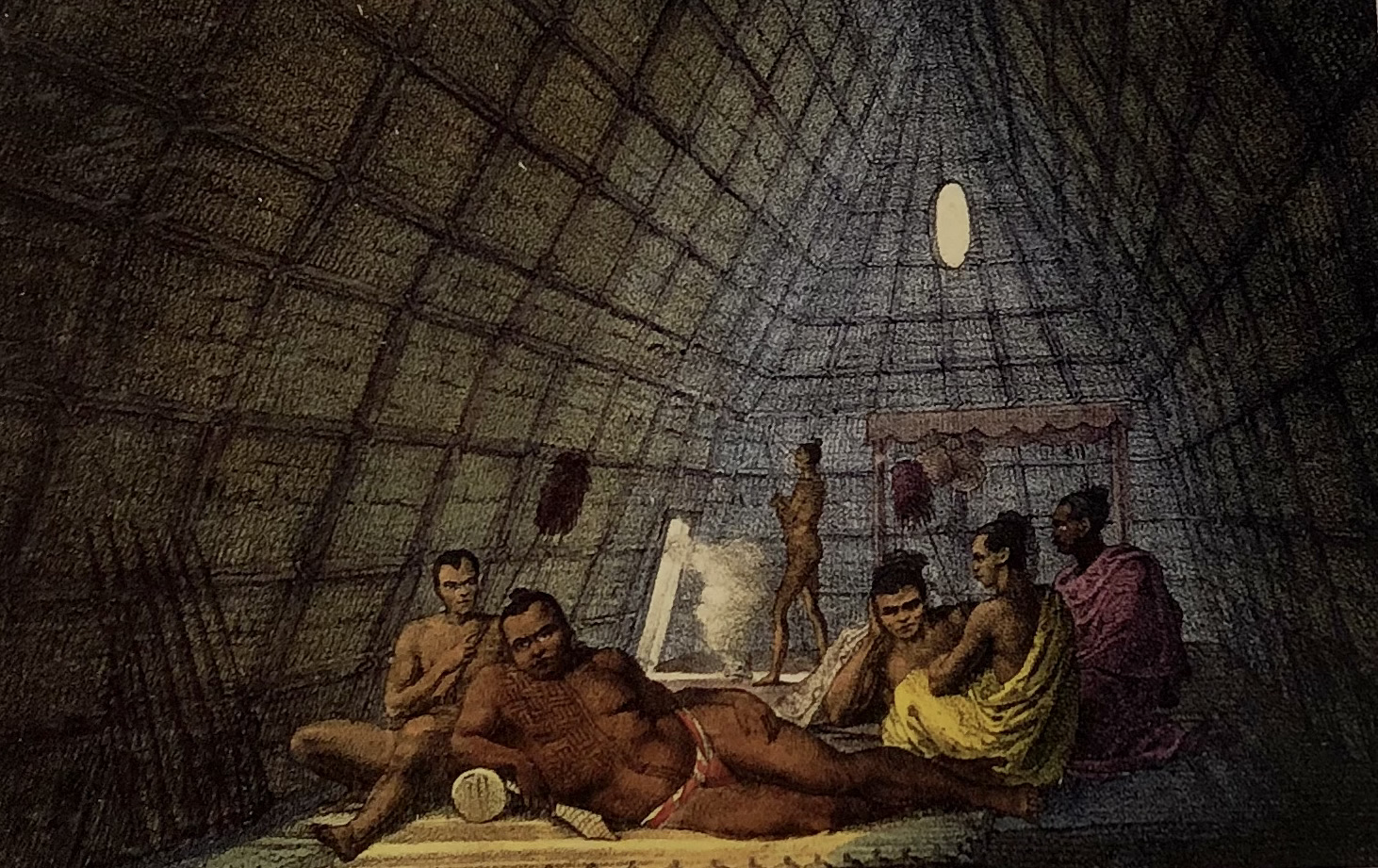

"Inside the house of the Sandwich Islands chiefs", hand coloured lithography, 8 x 27 cm, circa 1822, Jean-Augustin Franquelin afterLouis Choris, Honolulu Museum of Art © CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, p. 62.

In the 1820s, not long after the missions arrived in Hawaii, the feathered objects took a new sense. They could be presented for special occasions such as school exams, commemorations, weddings, funerals or more political events like the advent of a new sovereign. Thus, they were used in a newly manner in order for the royal family and high-rank people to distinguish themselves from the maka‘āinana, common people.14 In this context, « kāhili helped authenticate the evolving nation and added color and spectacle to the royal court ».15 As such, the example of the pair of kāhili named Ka’olohakaakeawe is very interesting. Ka‘olohaka was a chief from the island of Moloka‘i at the beginning of the 18thth century and he gave his name to one kāhili which belonged to the Kamehameha House (1810-1874). After being used by the family and put, for instance, near Kamehameha III’s coffin (1813-1854) at his funerals, the King Kalākaua (1838-1891, Kalākaua House) gave it to his sister, Lili’uokalani (1838-1917). She had the bone parts which composed the kumu (pole) taken away and buried them in the Mauna’ala royal mausoleum. At her request, Naheana, her featherworker, divided the feathers of the kāhili in order to have a second one to create a pair. The legitimacy of Kalākaua was contested and the seizing of this kāhili and, most of all, of its name - of an old Kānaka maoli chief - allowed him to legitimate his power.16

In the 19thth century, kāhili étaient principalement utilisés pendant les cérémonies funéraires. Ils étaient installés autour des cercueils, portés au moment de la procession funèbre pour rejoindre le mausolée, etc. Éventer le mort ou son cercueil pendant toute la veillée était une marque de respect : « Agiter les kāhili consistait à réaliser un mouvement très structuré et discipliné, insistant sur la précision et la synchronisation, et il nécessitait concentration, coordination, endurance et des éléments de chorégraphie ».17 The royal funerals were made more complex and, during the ceremonies, the number of kāhili aux cérémonies funéraires augmente. Il y en avait par exemple soixante quatorze aux funérailles du Roi Lunalilo (1835-1874).

Keopuolani funeral procession, watercolor, 12,7 x 20,3 cm, 1825, William Ellis (?), Hawaiian Mission Houses, HMCS Library, 73.5 NM © CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press.

On 17 January 1893, the Kānaka maoli monarchy was overthrown and the United-States created a temporary government. The territory was officially annexed in 1898 which resulted in the feather artefacts like the kāhili to be taken away from the ‘Iolani Palace, which was the last royal residence standing. They were then relegated to the storage and exhibition rooms of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum where they were long perceived as testimonies of an old and bygone period. However, they are now, as well as the other feather objects, elevated to the status of symbols of the Kānaka maoli identity.

Garance Nyssen

Cover picture: Abigail Kinoiki Kekaulike Kāhili Room, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, 2015, photographie de Hal Lum et de Masayo Suzuki, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum Archives © CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press.

1 Marques Hanalei Marzan et Samuel M. ‘Ohukani‘ōhi‘a Gon III, 2015. « The Aesthetics, Materials, and Construction of Hawaiian Featherwork ». In CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, p. 35.

2« Feather standard, symbol of royalty… to brush, sweep, switch », cité par ROSE, Roger G., CONANT, S. et KJELLGREN, E. P., 1993. « Hawaiian standing kāhili in the Bishop Museum: An ethnological and biological analysis », The Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol.102, n°3, p. 279.

3 Ibid, p. 279.

4 Ibid, pp.284-5.

5 « one of the traditional residing places of a person’s mana or spirituel power », Ibid, pp.286-8.

6 HOOPER, Steven (dir.), 2006. Pacific Encounters, Art & Divinity in Polynesia, 1760-1890. Wellington, Te Papa press, p. 43.

7 ROSE, Roger G., CONANT, S. et KJELLGREN, E. P., 1993. « Hawaiian standing kāhili in the Bishop Museum: An ethnological and biological analysis », The Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol.102, n°3, pp.289-91.

8 « Trough feather adornment, the mana of the gods was extended to the chiefs », Marques Hanalei Marzan et Samuel M. ‘Ohukani‘ōhi‘a Gon III, 2015, « The Aesthetics, Materials, and Construction of Hawaiian Featherwork ». In CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, p.31.

9 TE RANGI HIROA (BUCK, P. H), 1957. Arts and Crafts of Hawaii. Honolulu, Bishop Museum Press, pp.217-8.

10 Marques Hanalei Marzan et Samuel M. ‘Ohukani‘ōhi‘a Gon III, 2015, « The Aesthetics, Materials, and Construction of Hawaiian Featherwork ». In CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, p.26.

11 Adrienne L. Kaeppler, « Hawaiian Featherwork in the Age of Exploration ». In CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 46-8.

Jocelyn Linnekin émet toutefois l’hypothèse que les femmes pouvaient éventuellement, elles aussi, réaliser les capes en plumes : LINNEKIN, Jocelyn, 1988. « Who made the feather cloaks? A problem in Hawaiian gender relations », The Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol.97, n°3, pp. 265-280.

12 Roger R. Rose, « The Kāhili Standards of Hawai’i ». In CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, p. 60.

13 « Although [they] provided practical benefits of personal cooling […], they served primarily to mark the presence and spiritually protect an important individual of ali’i or chiefly rank ». ROSE, Roger G., CONANT, S. et KJELLGREN, E. P., 1993. « Hawaiian standing kāhili in the Bishop Museum: An ethnological and biological analysis », The Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol.102, n°3, p. 274.

14 Stacy L. Kamehiro, « Featherwork in the Hawaiian Monarchy Period ». In CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, p. 86.

15 « kāhili helped authenticate the evolving nation and added color and spectacle to the royal court ». Roger R. Rose, « The Kāhili Standards of Hawai’i ». In CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, p. 64.

16 Ibid, pp. 67-8.

17 « Kāhili waving was highly structured and disciplined, emphasizing precision and synchronized movement, and it required concentration, coordination, stamina, and elements of choreography », Ibid, p. 72.

Bibliography:

- BRIGHAMS, W. T., 1899-1918. Hawaiian feather work. Honolulu, Bishop Museum Press.

- CALDEIRA, L., HELLMICH, C., KAEPPLER, A. L., KAM, B. L., et ROSE, G. R. (ed.), 2015. Royal Hawaiian Featherwork Nā Hullu Ali’i, San Francisco. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press.

- HOOPER, Steven (dir.), 2006. Pacific Encounters, Art & Divinity in Polynesia, 1760-1890. Wellington, Te Papa press.

- LINNEKIN, Jocelyn, 1988. « Who made the feather cloaks? A problem in Hawaiian gender relations », The Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol.97, n°3, pp. 265-280.

- ROSE, Roger G., CONANT, S. et KJELLGREN, E. P., 1993. « Hawaiian standing kāhili in the Bishop Museum: An ethnological and biological analysis », The Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol.102, n°3, pp. 273-304 .

- TE RANGI HIROA (BUCK, P. H), 1957. Arts and Crafts of Hawaii. Honolulu, Bishop Museum Press.