*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

On 28 June 1871, when questioned by the war council that was to judge the former Communards, Louise Michel demanded:

"Since it seems that every heart that beats for liberty is only entitled today to a little bit of lead, I claim my share!"1

Un mois plus tôt elle a participé, aux côtés de ses camarades de lutte, aux combats de rue de La Semaine sanglante (du 21 au 28 mai), épisode final de la Commune de Paris au cours duquel l’insurrection est violemment écrasée par le pouvoir central établi à Versailles. La Commune de Paris (18 mars 1871 – 28 mai 1871) est une organisation politique insurrectionnelle refusant de reconnaître l’autorité du gouvernement français à majorité monarchiste (Gouvernement Jules Dufaure 1) élu au suffrage représentatif le 13 février 1871. Le soulèvement intervient à la suite de la guerre franco-prussienne de 1870, durant laquelle les parisiens subissent quatre mois de siège qui provoquent famine, forte mortalité et émeutes, et encouragent le gouvernement à signer l’armistice au prix de la reddition de Paris (le 28 janvier 1871). Dans un Paris républicain, les tenants de la démocratie directe et ceux qui refusent la reddition s’organisent autour d’un projet politique de type libertaire et social.2 Comme d’autre communes insurrectionnelles (Lyon, Marseille, Saint-Étienne…), la Commune de Paris est écrasée militairement par le gouvernement français, mettant fin à la guerre civile de 1871. Plusieurs milliers de Parisiens sont tués durant les combats de la Semaine sanglante, 40 000 arrêtés, et 13 000 communards sont jugés à la chaîne par les tribunaux militaires.3 Le 24 mai, pour faire libérer sa mère, Louise Michel se rend.4 Elle est détenue successivement au camp de Satory, à la prison des Chantiers à Versailles puis à la maison de correction de Versailles.

Louise Michel portrait at the Chantiers prison in Versailles, Ernest Charles, 1871. © Musée Carnavalet

At her trial, she claimed the crimes and offences of which she was accused, and called for "the Satory post"5, i.e. the firing squad through which important figures of the rebellion and some of her closest friends passed. In December, she was sentenced by the war council to deportation for life to a fortified compound. It will not be the lead or the post of Satory, it will be New Caledonia.

In the New Caledonian prison

The idea of an ultramarine penal colony - which would have the double advantage of removing from the metropole those elements of society deemed to be harmful and of carrying out a forced settlement of the least attractive territories of the French colonial empire6 - dates back to before the annexation of the New Caledonian archipelago to France (in 1853). As early as 1850, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, then President of the Republic, said about the prison population of the Toulon, Brest and Rochefort prisons at the Assembly:

"Six thousand convicts in our prisons place an enormous burden on the budget, are becoming increasingly depraved and are a constant threat to society. It seems to me possible to make the penalty of forced labour more effective, more moralising, less expensive and more humane, by using it for the progress of French colonisation."7

The law on deportation was passed in 1854, responding to the urgent need to close the metropolitan prisons. Guyana, which was closer, was the first to be chosen as a "land of great punishment"8, but the climatic and sanitary conditions there were such that the mortality rate among the inmates and warders soon became unacceptable. At the same time, New Caledonia attracted few settlers, although the land appeared to be fertile and the subsoil rich in minerals.9 Very remote (four to six months' journey across the oceans), it was frightening because of the resistance the Kanak put up against the colonial power and because of the suspicions of cannibalism that the first European explorers had cast on them. In an 1861 report entitled Essai sur la colonisation pénale à la Nouvelle-Calédonie (Essai on the penal colonisation in New Caledonia), the naval officer Charles Guillain (later the first governor of New Caledonia) supported the already widespread idea that, without recourse to this forced "transportation" of convicts, "[this] Oceanic possession would be of no serious use."10

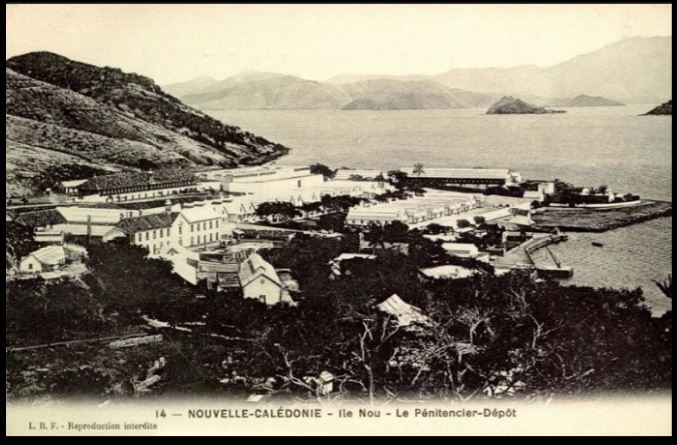

View of the Nou Island prison, postcard - © DR

The prison opened in 1864. Further establishing the French presence in New Caledonia, the law of 1854 obliges convicts sentenced to more than eight years of hard labour to spend the rest of their lives there. Convicts sentenced to less than eight years also participated in penal colonisation once they were free, since the law ratified the principle of "doubling" the sentence, i.e. the obligation to spend a period of time in the archipelago equal to the duration of the forced labour, by exploiting the land on prison farms.11

The arrival of the Communards

The death penalty for political reasons having been abolished in 1848, the Communards who did not fall during the Bloody Week and who escaped execution on other charges became convicts, for 4500 of them. The leaders like Louise Michel were sentenced to deportation to a fortified enclosure. The participants that were judged to be the least resistant were deported. Their families were authorised to accompany them, always with a view to strengthening the French presence in New Caledonia, and to encourage the communards never to return to Paris. Their removal from the metropolis was a response to the fear of the government in power: that the revolutionary ideas carried by these thousands of insurgents would spread.12

No matter what, there, thousands of miles from the power of Versailles, they bear witness to the hell of the prison, where common law prisoners did not necessarily have the resources or the network necessary to make their voices heard. The descriptions they gave are far from the pious wishes of the legislators, who advocated rehabilitation and the redemption of offences through work on the land. Mistreatment and humiliation are legion (ball and chain, two by two, shoes as soup bowls). The few letters that escape censorship set the tone:

"New Caledonia is a slaughterhouse of men, it has been put there in the antipodes in order to spare your delicacy, so that you do not smell the odour of the crime and that you do not hear the beatings on the heads of the captives."13

Generally more qualified than the rest of the prison population, the Communards were nevertheless treated better and requisitioned for specific tasks, thereby avoiding the most arduous work.

Kanak, Kabyles and Communards: the impossible dialogue of insurgents

In the metropolitan prisons where they awaited deportation, and later in New Caledonia, the Parisian insurgents rubbed shoulders with the Kabyle insurgents of 1871, protagonists of one of the largest uprisings in Algeria against the colonial power, which brought together up to a third of the territory behind the Mokrani family and the Rahmanyia brotherhood.14

Concordance of dates, desire for self-determination, similarity of sentences (like the communards, some Kabyle insurgents were judged as common criminals and executed, the others deported... without their families this time): some Parisian commentators such as Jean Allemane, were quick to identify with their fellow prisoners:

"I learned that the newcomers were defeated like me, and that they were treated in the same way: the Algerian councils of war had rivalled those of Versailles in their zeal. [...]Night was approaching; dark and silent, the vanquished of Algeria and the vanquished of the Commune sat side by side thinking of those they loved, of the collapse of their existence, of the annihilation of their dream of freedom ."15

Some become opponents at draughts, others, like Eugène Mourot and Azziz ben Cheikh el-Haddad, friends for life. 16 In contact with the Kabyles, these "viscerally "patriotic" <communards, for whom the validity of the colonial project is not really in question"17, become more critical of France's colonial policy:

"What they told me about the abuses and thefts they had been subjected to over and over again made me feel indignant and ashamed for our country."18

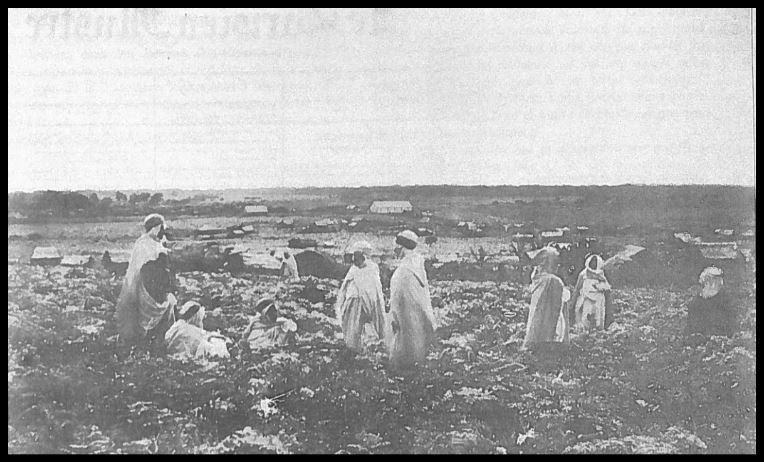

Arab camps, Isle of Pines, N.C., Hugan lithograph, 1876 - © Archives territoriales de Nouméa

However, this questioning of colonisation does not seem to include the Kanak question, or only marginally. Communards and Kabyle rebels even went so far as to fight alongside the French administration when it came to crushing the great Kanak revolt of 1878.

In contrast to the fraternal feelings that the Parisian deportees developed for their Algerian comrades, it is at best indifference, at worst contempt, that inspires them their Kanak neighbours. Like other Europeans of their time, the Communards were steeped in the racist theories of anthropologists and explorers who made the Kanak 'prehistoric people without history'.19 Moreover, since annexation to France, the Kanak have multiplied acts of resistance against the colonists, a majority of whom, it should be remembered, are former convicts. In parallel with this resistance - which disrupted the colony's expansion plans - deprivation, disease and progressive demoralisation due to land dispossession led to such a high mortality rate among the Kanak that many commentators of the time predicted the imminent disappearance of their culture and its last representatives. 20 Some French ideologists then saw the medium-term annihilation of the Kanak population as the natural outcome of the colonial process. Among the deportees, whose contacts with the Kanak remained extremely marginal, few found fault with this.

Most of the Communards were convinced that they were anti-clerical, and they also judged the Kanak converts very harshly, like Francis Jourde, who said of the Kouniés of the Pine Island:

"A large population gathers around the religious establishment of which it has become the blind and submissive slave."21

Above all, from 1876 onwards, with the arrival of a republican majority in the Chamber of Deputies, the hope of a general amnesty for the former insurgents was on everyone's mind. After five years in prison, the former insurgents knew the cost of challenging the sovereignty of the French state. So, when in 1878 a great drought and the project to establish a new penal establishment triggered the conflagration of a territory already under tension since the setting up of reserves two years earlier, it was quite natural that Communards and Kabyle came to swell the ranks of their former oppressor to quell the rebellion. The Kabyle leader Bou Mezrag el-Mokrani offered his services to the governor of New Caledonia and "with a small troop of liberated, deported or convicted Arabs [sic.], of whom he was given command, he served as a scout [for the French soldiers]". 22 The Communard Jean Allemane, who a few years earlier wrote of his solidarity with the Kabyle insurgents, depicts Kanak rebels as "cannibalistic" and "with bestial passions". 23 One of his comrades tells:

"At the Ducos peninsula we thought that in the presence of the Canaque [sic.] insurrection it was our duty not to fall into a cowardly sleep and to defend the French government. One of our own Rousseau senior wrote a letter to the government in which he proposed to put himself at the head of a number of comrades and go and fight the savages."24

Yet another, in an irony of fate that would not please his comrades, proposed that the Kanak rebels be... deported to some French possessions in need of labour.25 For her part, Louise Michel took up the cause of the Kanak Insurrection. She was one of the few.

In this turn of history, which made the insurgents of 1871 the armed wing of the repression of 1878, it is difficult to determine how much of this was political conviction and how much was personal calculation in order to obtain a pardon. The truth probably lies somewhere in between. Individual pardons are indeed beginning to be granted to political deportees. The general amnesty for the Communards was finally voted in 1880, the one for the Algerians fifteen years later. In the meantime, Louise Michel, back in metropolitan France, published Légendes et chansons de gestes Canaques ("Legends and songs of Canaque gestures"), the subject of the next article in this series, in memory of her Caledonian years.

Margot Duband

Cover picture : Nouméa. Arrival of the Danaé. The deportees as they disembark. Le Monde Illustré, 1873, p. 88. In PISIER, G, 1971. « Les déportés de la Commune à l’île des Pins, Nouvelle-Calédonie, 1872-1880 ». Journal de la Société des océanistes. N°31, Tome 27, pp. 103-140.

To go further: see Médiapart's series "Le projet colonial en Nouvelle-Calédonie". https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/dossier/france/le-projet-colonial-en-nouvelle-caledonie

1 MICHEL, L., 2000 [1904]. Histoire de ma vie : seconde et troisième parties. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 11.

2 Opening citizenship to foreigners, prohibition of salary deductions, introduction of a maximum salary for civil servants, creation of specifications and a minimum income for public contracts, beginnings of self-management in companies, recognition of free unions, outline of equal pay for men and women, separation of church and state in schools and hospitals...

3 DELAPORTE, L., 2018b. « Déportés en Nouvelle-Calédonie: l’improbable rencontre des communards et des insurgés algériens ». Médiapart, 19 août 2018.

4 MICHEL, L., 2000 [1904]. Histoire de ma vie : seconde et troisième parties. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 36.

5 MICHEL, L., 2000 [1904]. Histoire de ma vie : seconde et troisième parties. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 11.

6 DUBAND, M., 2019. “1878 : deux regards sur l’Histoire ». In CASOAR https://casoar.org/2019/10/30/1878-deux-regards-sur-lhistoire/

7 BARBANÇON, L., 2003. L’Archipel des forçats : Histoire du bagne de Nouvelle-Calédonie (1863-1931). Villeneuve d’Ascq, Presses universitaires du Septentrion.

8 DELAPORTE, L., 2018a. « Quand la France choisit de « vomir ses criminels » en Nouvelle-Calédonie ». Médiapart, 15 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/150818/quand-la-france-choisit-de-vomir-ses-criminels-en-nouvelle-caledonie

9 DELAPORTE, L., 2018a. « Quand la France choisit de « vomir ses criminels » en Nouvelle-Calédonie ». Médiapart, 15 août 2018.

10 DELAPORTE, L., 2018a. « Quand la France choisit de « vomir ses criminels » en Nouvelle-Calédonie ». Médiapart, 15 août 2018.

11 DEBIEN-VANMAI, C., 10 août 2010. « Le rôle des bagnards dans la colonisation pénale en Nouvelle-Calédonie ». In HG/NC, le site académique d’histoire-géographie de Nouvelle-Calédonie, http://histoire-geo.ac-noumea.nc/spip.php?article164.

DUBAND, M., 2019. “1878 : deux regards sur l’Histoire ». In CASOAR https://casoar.org/2019/10/30/1878-deux-regards-sur-lhistoire/

12 DELAPORTE, L., 2018b. « Déportés en Nouvelle-Calédonie: l’improbable rencontre des communards et des insurgés algériens ». Médiapart, 19 août 2018.

13 Anonyme, cité dans DELAPORTE, L., 2018b. « Déportés en Nouvelle-Calédonie: l’improbable rencontre des communards et des insurgés algériens ». Médiapart, 19 août 2018.

14 DROZ, B., 2009, « Insurrection de 1871: la révolte de Mokrani ». In L’Algérie et la France. Paris, Robert Laffont, pp. 474-475.

15 DELAPORTE, L., 2018b. « Déportés en Nouvelle-Calédonie: l’improbable rencontre des communards et des insurgés algériens ». Médiapart, 19 août 2018.

16 Azziz ben Cheikh el-Haddad, a leading figure in the Kabyle insurrection of 1871, died in Paris in 1895 during a visit to his communist friend. A contribution was organised to have his body repatriated to Algeria. DELAPORTE, L., 2018c. « Kanak et déportés: le rendez-vous manqué ». Médiapart, 21 août 2018.

17 DELAPORTE, L., 2018b. « Déportés en Nouvelle-Calédonie: l’improbable rencontre des communards et des insurgés algériens ». Médiapart, 19 août 2018.

18 Le journaliste, communard et futur anti-dreyfusard Henri Rochefort, cité dans DELAPORTE, L., 2018b. « Déportés en Nouvelle-Calédonie: l’improbable rencontre des communards et des insurgés algériens ». Médiapart, 19 août 2018.

19 DOTTE, E., 2017. « How Dare Our ‘Prehistoric’ Have a Prehistory of Their Own?! The interplay of historical and biographical contexts in early French archaeology of the Pacific », Journal of Pacific Archaeology 8 (1), p. 31.

20 DUBAND, M, 2016. La mission archéologique et ethnographique en Nouvelle-Calédonie de Marius Archambault (1898-1920). Paris, mémoire d’étude de l’école du Louvre, p. 46.

21 DELAPORTE, L., 2018c. « Kanak et déportés: le rendez-vous manqué ». Médiapart, 21 août 2018.

22 DELAPORTE, L., 2018c. « Kanak et déportés: le rendez-vous manqué ». Médiapart, 21 août 2018.

23 DELAPORTE, L., 2018c. « Kanak et déportés: le rendez-vous manqué ». Médiapart, 21 août 2018.

24 MAYER, S., 1880. Souvenirs d’un déporté, étapes d’un forçat politique. Paris, E.Dentu Editeur, p. 407.

25 DELAPORTE, L., 2018c. « Kanak et déportés: le rendez-vous manqué ». Médiapart, 21 août 2018.

Bibliography:

- BARBANÇON, L., 2003. L’Archipel des forçats : Histoire du bagne de Nouvelle-Calédonie (1863-1931), Villeneuve d’Ascq. Presses universitaires du Septentrion.

- DEBIEN-VANMAI, C., 10 août 2010. « Le rôle des bagnards dans la colonisation pénale en Nouvelle-Calédonie ». In HG/NC, le site académique d’histoire-géographie de Nouvelle-Calédonie, http://histoire-geo.ac-noumea.nc/spip.php?article164, dernière consultation le 08 octobre 2019.

- DELAPORTE, L., 2018a. « Quand la France choisit de « vomir ses criminels » en Nouvelle-Calédonie ». Médiapart, 15 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/150818/quand-la-france-choisit-de-vomir-ses-criminels-en-nouvelle-caledonie , dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- DELAPORTE, L., 2018b. « Déportés en Nouvelle-Calédonie: l’improbable rencontre des communards et des insurgés algériens ». Médiapart, 19 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/190818/deportes-en-nouvelle-caledonie-l-improbable-rencontre-des-communards-et-des-insurges-algeriens, dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- DELAPORTE, L., 2018c. « Kanak et déportés: le rendez-vous manqué ». Médiapart, 21 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/210818/kanak-et-deportes-le-rendez-vous-manque, dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- DELAPORTE, L., 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste , dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- DOTTE, E., 2017. « How Dare Our ‘Prehistoric’ Have a Prehistory of Their Own?! The interplay of historical and biographical contexts in early French archaeology of the Pacific », Journal of Pacific Archaeology 8 (1), pp. 25-34.

- DROZ, B., 2009. « Insurrection de 1871: la révolte de Mokrani ». In L’Algérie et la France. Paris, Robert Laffont, pp. 474-475.

- DUBAND, M., 2016. La mission archéologique et ethnographique en Nouvelle-Calédonie de Marius Archambault (1898-1920). Paris, mémoire d’étude de l’école du Louvre.

- DUBAND, M., 2019. “1878 : deux regards sur l’Histoire ». In CASOAR https://casoar.org/2019/10/30/1878-deux-regards-sur-lhistoire/, dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- MAYER, S., 1880. Souvenirs d’un déporté, étapes d’un forçat politique. Paris, E.Dentu Editeur.

- MICHEL, L., 2000 [1904]. Histoire de ma vie : seconde et troisième parties. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon.

Pingback: A gyarmatosítás legsötétebb emlékeit idézi a kormány vendégmunkásokra vonatkozó törvénye « Mérce