*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

You may have seen them, those intriguing posters in the streets of Paris: blue, yellow, an unidentified object occupying the space, and a word that is equally unknown to most of us: Maro 'Ura. At most, the subtitle helps us to see more clearly: "a Polynesian treasure". A new surprise: how can this object, which seems so old, so damaged, and whose usefulness is hard to distinguish, be a "treasure"?

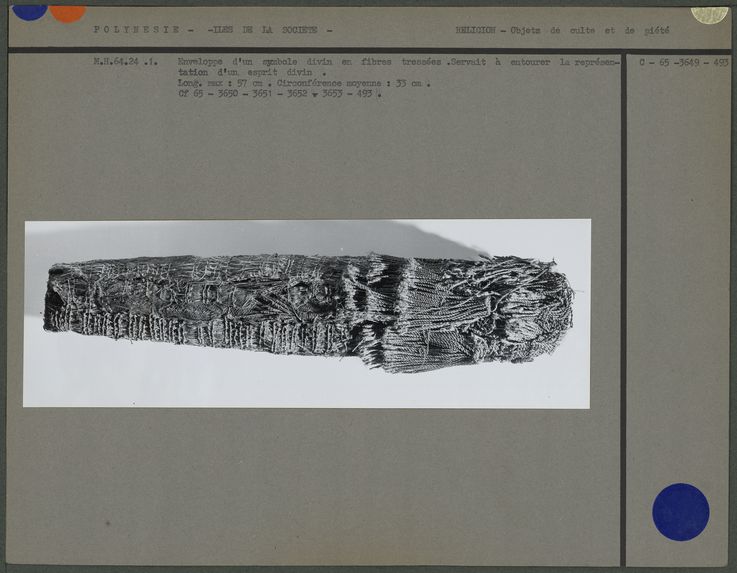

Fragment of the supposed maro' ura - Source: © musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, picture by Pauline Guyon.

To solve this mystery, head to the musée du quai Branly: the exhibition "Maro 'Ura. A Polynesian Treasure" is being held in the Martine Aublet studio from 19 October 2021 to 9 January 2022. While we learn, at the entrance, what is a maro ’ura, the mystery remains. Specific to the Society Islands, the maro ’ura is a belt of red feathers that only the ari’i rahi – the great sacred leaders – could wear. Kept away from the eyes of ordinary people, it was only worn on exceptional occasions. Some European travelers described this object in their travel accounts, but from the beginning of the 19th century, they seem to disappear. We only have knowledge of one representation of these sacred belts, and there, a priori, no example of these objects kept in museum collections.

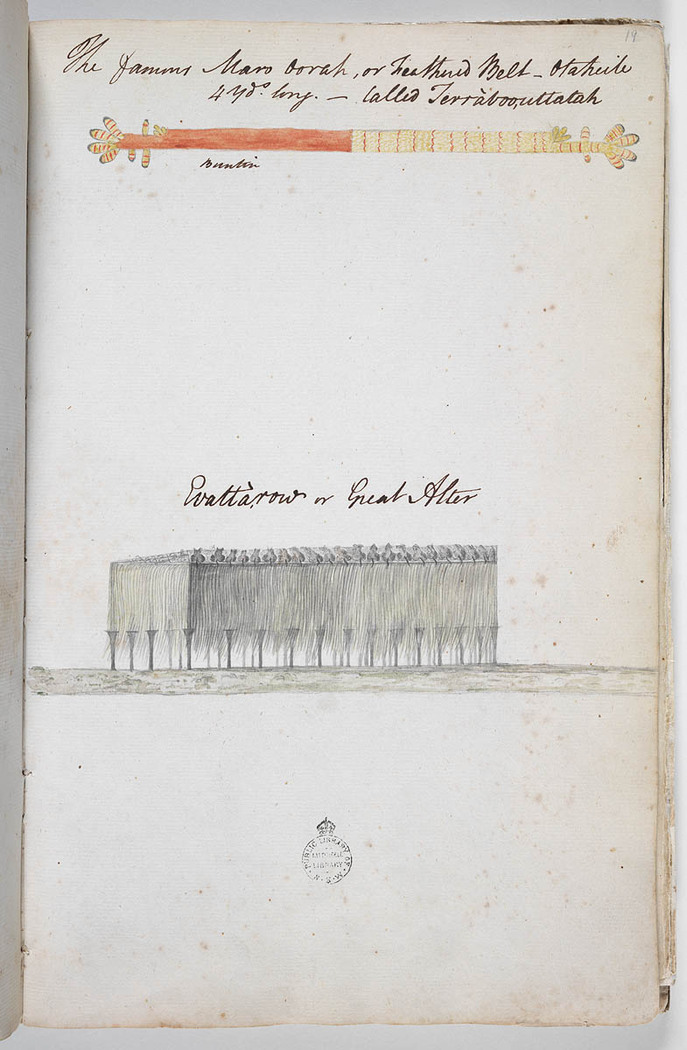

Dated 1791-1793, this watercolour drawing is the only known representation of a maro 'ura. It was made by William Bligh (1754-1817). Below, a representation of a marae. - Source: Médiathèque historique de Polynésie.

And it is here, in this "a priori", that the exhibition's purpose lies. For this object on the poster, so far from our usual aesthetic criteria, might be a fragment of this famous maro ’ura, the polynesian treasure.

The exhibition is constructed like a police investigation, attempting to draw the visitor into the investigations surrounding this mythical object. It all began in 2016, when Guillaume Alevêque, a post-doctoral researcher at the musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, hypothesised that this piece of tapa1, of feathers and plant fibres, could be a maro ’ura. The history of this enigmatic object is traced back to its first mention in 1818 by Pomare II, when it was sent to Dr Thomas Haweis, Director of the London Missionary Society2, until the recently conducted research.

The daring and playful scenography presents the fascinating journey of this object on a panel that looks like a police file. But where do the hypotheses about this object come from? Acquired by the Musée de l'Homme in 1964, it was first identified as an envelope for to’o and the story could have ended there.

Nevertheless, the composition of this strange object does not allow it to be linked to a typology of Polynesian artefacts known to us now: tapa is attached on a braided support. The composition of this piece is unprecedented for a Polynesian object, with feathers, plant-fibre cords and textile fragments.

"Envelope of a divine symbol": this identification sheet dated from 1965 presents the supposed maro' ura fragment as a to'o envelope. - Source: musée du quai Branly, identification number pp0102328, print on baryté paper mounted on cardboard.

The story becomes even more exciting in the light of recent discoveries about the composition of this supposed fragment of maro ’ura. In 1767, a red flag was planted in Tahiti by Tobias Furneaux, second lieutenant of the Dolphin, led by the British captain Samuel Wallis, and the first European to set foot on the island. This red flag was integrated into a maro ’ura shortly afterwards. But, surprise! Recent analyses show that our fragment of fabric contains pieces of a red wool dyed with madder, a process commonly used by the English army from the 17th century.

Without knowing anything about this case, you would probably never have thought that you could become so passionate about a piece of cloth! And yet, it works: reading this fake police report plunges us into a real detective story. How did a piece of red wool end up in such an ancient Polynesian object, knowing that no wool was ever produced in Polynesia in the 18th century? Could this unassuming object be a fragment of a mythical maro ’ura? Is this the only remaining sample of this object of crucial importance to ancient Tahitian society? Does it carry, in addition to its original sacredness, the priceless testimony of the arrival of the first Europeans on Tahiti?

To these crucial questions, others are added, more pragmatic this time... We are in a museum, in an exhibition: it is a question of giving to see. But what should we show here? A single object whose appearance will probably not captivate the crowds, a single representation of a maro ’ura... But it would take more than that to discourage the curators of this surprising and fascinating exhibition. And so it is in this way that Maro ’ura. A polynesian treasure manages to draw, in hollow, the delicate portrait of an absent person. The first showcase displays the supposed maro ’ura alongside the to’o that it originally packed, and āraimoana, small feathered elements that were exchanged, hung, and unhung from the to’o during the pai’atua, packing ceremony of the to’o. Once this "visible" part is over, the exhibition focuses on presenting various Polynesian objects with characteristics similar to those of the maro ’ura. It is a question of showing what is made with materials that are close to us and that also fulfill the function of objects of power or sacredness. The whole of Polynesia is called upon, from the Marquesas to Hawaii, and we are treated to feather cloaks, chiefs' helmets, orators' staffs and fans... We do not shy away from our aesthetic pleasure at such an accumulation of masterpieces. And, above all, beyond the pleasure we get from contemplating these showcases full of treasures, we perceive, through these sacred objects, the lost splendour of the maro ’ura.

Display case "Regal objects from Hawaii". - Photography by Garance Nyssen.

Light and Contrasts" showcase presenting objects from different parts of Polynesia. - Photography by Garance Nyssen.

What next? Is it real, is it fake, will we ever know? Maybe not. But in fine this exhibition, which highlights the strongest symbol of Tahitian power, also marks a new era in museum relations between Tahiti and France. The exhibition is curated by Guillaume Alevêque, who initiated research on the maro ’ura, by Stéphanie Leclerc-Caffarel, head of the Oceania collections at the musée du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, as well as by Marine Vallée, assistant curator at the Musée de Tahiti et des îles, and by the museum's entire scientific team. This unprecedented collaboration heralds a new way of producing exhibitions at the musée du quai Branly: the work is carried out in partnership with the museums where the objects originate from. The discourse is created jointly, in this case with a Polynesian point of view on Polynesian objects. Another remarkable novelty is that the texts are translated entirely into reo tahiti (Tahitian) and the Tahitian text recited at the investiture ceremony of the ari’i rahi is read by a Tahitian, the Minister of Culture of French Polynesia, Heremoana Maamaatuaiahutapu.

3D image showing the future exhibition space at the musée de Tahiti et des îles. A central wall will be dedicated to the exhibition of the maro ‘ura. ©Musée de Tahiti et des îles

Finally, this exhibition is as much a presentation exhibition of this object as a farewell exhibition for the musée du quai Branly. In 2019, a deposit agreement was signed between the musée du quai Branly and the Musée de Tahiti et des Îles. At a time when restitution are at the centre of discussions, this agreement may raise questions, but it is impossible to return a French object to... France. Tahiti being French, a restitution is impossible. The object will therefore be returned to its native land, and will be displayed in the new exhibition of the Musée de Tahiti et des îles, in the "New Era" section. This hypothetical maro ’ura has become the symbol of the new relations between France and Tahiti, of the incessant back and forth of objects, people and ideas... Maro ’ura or not, this object seems to have kept the power to make Tahiti shine in the world through centuries!

Camille Graindorge

A million thanks to Garance Nyssen for giving me a private tour of the exhibition.

Featured image: the display case showing the supposed fragment of Maro ’ura, the to’o and the āraimoana. Photographie par Garance Nyssen.

1 Tapa is a fabric made of bark found throughout Oceania. See the article by Garance Nyssen, “T’a(s)pa(s) vu mon tapa ?”

2 The London Missionary Society is a society of anglicans missionaries funded in 1795 who was partly active in Oceania. Source : BNF catalogue BNF, collectivity note ; https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb12088501r

1 Comment so far