*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

Since the 1990s, an “archival turn” has been happening in contemporary art in Australia1 where artists have been engaging with archives, whether it be in museums, libraries, or archives per se. An influential artist at the forefront of this “new” movement re-reading the archive is the Wirardjuri (NSW, Australia)/Celtic ‘conceptual artist’2 Brook Andrew. Artist Brook Andrew can be regarded as an ‘archival mediator’3 who ‘remak[es and] remark[s …] anthropological or ethnographic objects’.4 It is his work The Island created in 2007-2008 after encountering photographic archives coming from the encyclopaedia Australien in 142 photographischen Abbildungen nach zehnjährigen Erfahrungen (translated as Australia in 142 Photographic Illustrations from 10 Years’ Experience and which we will be referring to as Australia) of the Prussian explorer William Blandowski in 2007 in Cambridge that we will be looking at in more details.

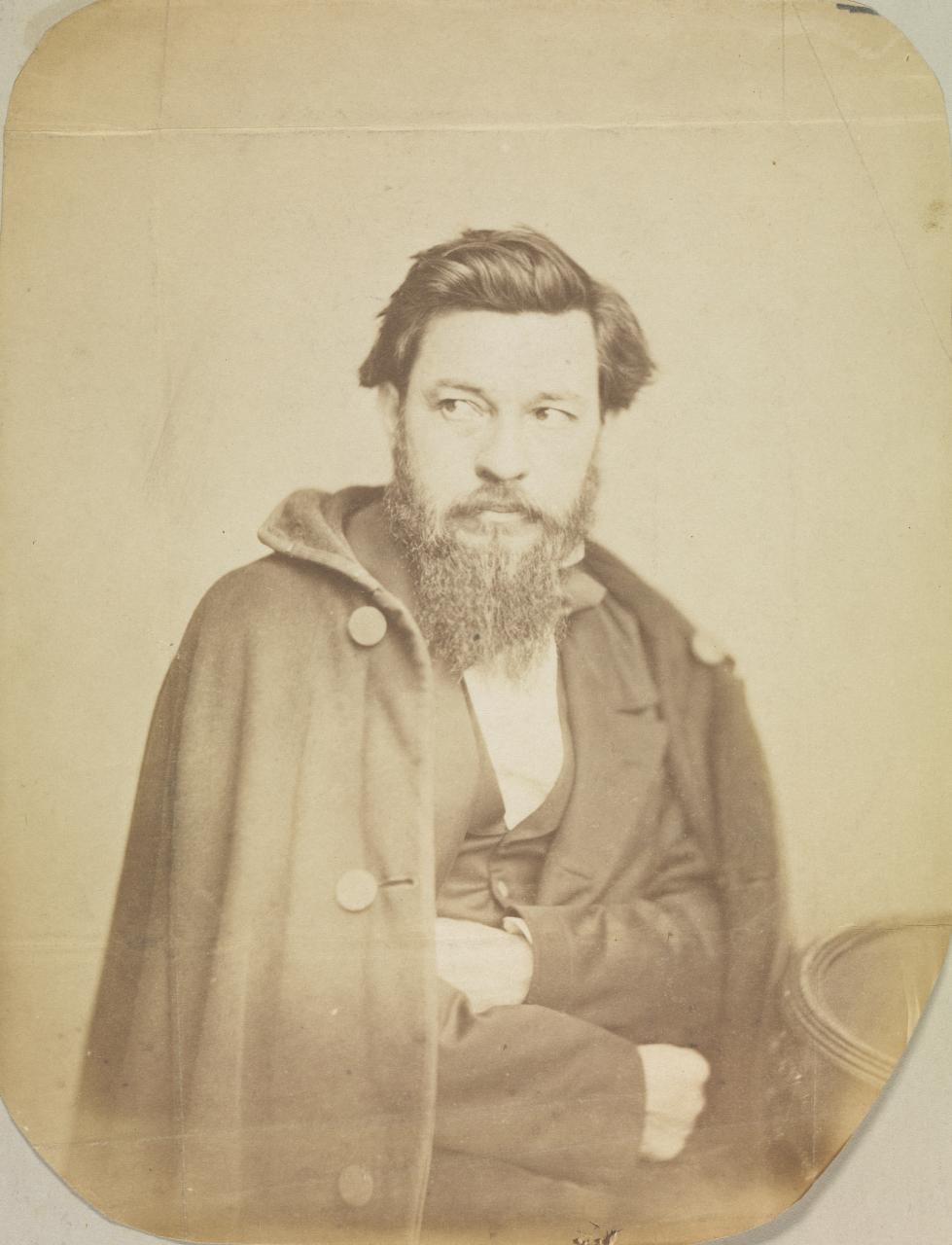

William Blandowski: Australia

Self-portrait of the zoologist William Blandowski, 1860.

Johan Wilhelm Theodor Ludwig von Blandowski, who we will refer to as William Blandowski (as he was known in Australia) was born in 1822 in Gleiwitz, Prussia (presently Gliwice, Poland) and died in 1878 in Bolesławiec, Prussia (presently Poland). After working in a mine and living all his life in Gleiwitz, Blandowski boarded theOcean on 5 May 1849 and sailed first to Adelaide where he arrived four months after his departure, and then went to Melbourne, Australia, where he stayed for ten years until 1859. He first went there to collect natural specimens for Hamburg

collectors but ended up doing much more.5 Indeed, he was a foundation member of the Geological Society of Victoria which then merged with the Victorian Institute for the Advancement of Science to create the Philosophical Institute of Victoria.6 Later on, Blandowski was appointed the first curator of the Natural History Museum in Victoria on 1st april 1854.

From 1856 to 1857, Blandowski went on an expedition to the confluence of the Murray and Darling Rivers (New South Wales), which was then little known to white settlers, in order to “collect” images and practices “before they disappeared”. During this expedition, he ‘employed Aboriginal men, women and children as collectors […] while Gerard Krefft,

second-in-command, managed the day-to-day business of the camp and catalogued and

illustrated the specimens’.7 But in 1859, after multiple expeditions, he had to return to Europe after being caught in some controversy; it seems he refused to ‘surrender the materials from the Murray River expedition to the government’.8 He left on the Prussian barque Mathilde, on 17 March 1859 and arrived in Hamburg in October 1859.9

Back in Gleiwitz, Blandowski employed Gustav Mützel (a student at the Berlin Academy of Art) from 1860 to 1861, to rework Krefft’s drawings and other sources, and make a cohesive ensemble.10 He also spent time giving lectures about his Australian explorations to academic societies, in order to try to gain support for his publication.11 He put all his time, energy and money in producing his encyclopaedia which was printed in 1862 in German. However, he failed to secure sufficient funding so that only two copies were printed, one of which is now in Berlin (Staatsbibliothek) and the other in Cambridge (Haddon Library). It is very likely that the volumes we know today asAustralia were a mock-up of what he hoped would be the final version.12

Although Blandowski chose to mention “photographic illustrations” in the title of the

encyclopaedia, it is quite misleading. Indeed, these “photographic illustrations” are nothing

but photographs of drawings. Choosing this denomination was a way for Blandowski to

‘capitalize on photography’s status at the time, as an advanced technology with a unique

capacity to represent nature’.13 There is hardly any doubt that he chose the albumen print technique and therefore photography to emphasize this newly discovered technique and for reproduction and cost purposes. Not only did the photographs give ‘a modern feel’14 to his encyclopaedia it also madeAustralia ‘a forerunner of the modern age of communication’.15 Furthermore, the use of photography allowed this work to survive despite the fact that almost none of the original sketches did.16 For his encyclopaedia and the work he achieved later in his life, Blandowski is regarded as the pioneer of Polish photography.

Australia was created in the Humboldtian tradition of empirical research, as ‘the Indigenous book to end all books, the last account of Aboriginal society’.17 Blandowski’s encyclopaedia can also be said to give a romantic account of Australia. He aimed at compiling a comprehensive pictorial collection based on first-hand investigations that summed up contemporary knowledge about Australia, based on his 4,000 items in sixteen bound volumes ready for the production of the encyclopaedia.18

Left: Frontispiece from Two Expeditions into the Interior of Southern Australia by Charles Sturt, 1833.

Right: William Blandowski, Plate 137: Aborigines of Australia: burial places near Budda in longitude 148° latitude 32° from a sketch by Capt. Sturt..

Because of the multiplicity of mediums that were produced over time (drawings, etchings, photographs), all the images in Blandowski’s encyclopaedia are highly curated. For example, Plate 137, which is used by Brook Andrew for The Island I, is itself adapted from the frontispiece of Charles Sturt’s Two Expeditions into the Interior of Southern Australia by Charles Sturt, 1833.19 Mützel, who worked in Gleiwitz with Blandowski to harmonise images for the encyclopaedia, brought some changes to Sturt’s engravings by cropping the original image, yet keeping a similar composition. Overall, and taking into consideration that images were highly curated, Australia and the images it comprises are highly significant historical statements as they depict one of the very first contacts with Aboriginal people and cultures, ‘that fleeting moment before everything changed’.20 Thus, Harry Allen talks aboutAustralia as ‘a view which is both timeless and in the past’21, an encyclopaedia which was not the last book on Indigenous people, but one which emphasized Aboriginal people as “the other” of the 19th century.

All in all, Blandowski’s encyclopaedia is a work curated by William Blandowski; but it also reflects a network of relationships between himself and draughtsmen, academics, Aboriginal people, scientists, etc. Little did he know that future Indigenous artist Brook Andrew would engage with it almost 150 years later.

Brook Andrew: The Island

As part of his text Remember How We See: The Island, Brook Andrew asks: ‘Where is truth in representation when myth-making is integral to history?’.22 This statement throws light on the set of relations between people and the encyclopaedia that are apparent in Blandowski’s Australia, more precisely, in the images compiled in it: this encyclopaedia, which is considered a historical document, was, as discussed previously, highly curated, thereby creating a mythical vision of Australia more than a truthful representation of it. In turn, Brook Andrew self-consciously created his own mythical representation through the realisation of his series The Island.

In June 2007, Brook Andrew encountered more than 300 reproductions of images from Blandowski’s encyclopaedia in the photographic archive of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge. From the images, Andrew created a series of six mixed media works of 3m x 2.5m made of heat-sealed foil onto cotton which was then screen printed.23

Left: William Blandowski, Plate 137: Aborigines of Australia: burial places near Budda in longitude 148° latitude 32° from a sketch by Capt. Sturt..

Right: Brook Andrew, The Island I, 2008, Mixed media, 250 x 300 x 5 cm.

L’origine de The Island I is directly created from Plate 137: Aborigines of Australia: burial places near Budda in longitude 148° latitude 32° from a sketch by Capt. Sturt.While Blandowski had already reworked Charles Sturt’s image, Andrew ‘rendered it more mystical and magical almost futuristic with this dome alone in the landscape, erasing the human figure completely’.24 Because of the technique used, the spaceship quality of the tomb is emphasized by cracking of the paint then revealing the metallic colour of the foil structure of the work.25

Left: William Blandowski, Plate 140: Aborigines of Australia: native tomb on the Lachlan River in longitude 143° latitude 33° after Oxley. Lachlan, longitude 143° latitude 33, d’après Oxley.

Right: Brook Andrew, The Island II, 2008, Mixed media, 250 x 300 x 5 cm.

The Island II is a rendition of Plate 140: Aborigines of Australia: native tomb on the Lachlan River in longitude 143° latitude 33° after Oxley. Lachlan, longitude 143° latitude 33, d’après OxleyAt first sight and despite the medium, this version of Plate 140 seems rather similar to that represented in Australia. Yet, Andrew disrupted the image by changing the trees in the original image into a ‘Germanic Forest with pine trees’ in order to make a direct reference to Blandowski’s origins.26

Left: William Blandowski, Plate 120: Aborigines of Australia: widows

mourning for their husband in the Lower Murray River.

Right: Brook Andrew, The Island III, 2008, Mixed media, 250 x 300 x 5 cm.

The Island III is not only a reproduction of Plate 120, Aborigines of Australia: widows mourning for their husband in the Lower Murray River, but also a reconstruction of many rituals combined in one. Indeed, the instantaneity that we associate today with photographs was far from common in the 19thth century. People would take the time to construct an image, while nowadays we tend to freeze moments in time.27

Left: William Blandowski, Plate 84: Aborigines of Australia: public ceremony removing a bone out of his body.

Right: Brook Andrew, The Island IV, 2008, Mixed media, 250 x 300 x 5 cm.

Contrary to the other works Andrew chose amongst Blandowski’s images, The Island IV does not represent death or burials but a ‘bizarre corroboree’, more precisely Plate 84: Aborigines of Australia: public ceremony removing a bone out of his body. With this work, Andrew “cropped” Blandowski’s version of the image to focus on the central part of the original image, also adding a blue tone contrasting with blacks and greys, thereby dramatizing the effect.28

Left: William Blandowski, Plate 67: Mammalia of Australia: kangaroo hunt.

Right: Brook Andrew, The Island V, 2008, Mixed media, 250 x 300 x 5 cm.

The Island V is an anguished version29 of Plate 67: Mammalia of Australia: kangaroo huntBy using the colour red and focusing on the figure of the ‘Godzillakangaroo’30 Andrew gives a satirical and political dimension to the original image: the Kangaroo figure, standing strong and tall, becomes a representation of Australia as a dominating political power.

Left: William Blandowski, Plate 123: Aborigines of Australia: natives smoking a dead (sic) to a mummy on Lake Alexandrina.

Right: Brook Andrew, The Island VI, 2008, Mixed media, 250 x 300 x 5 cm.

Finally, The Island VI is based on Plate 123: Aborigines of Australia: natives smoking a dead (sic) to a mummy on Lake Alexandrina. Once again, the colour red was used to emphasize the image of ‘mourning warriors cast[ing] their weapons aside and giv[ing] themselves up to grief.31

The use of colours is a way to dramatize the images and to transform them into some sort of advertising images in a consumer-culture fashion. Furthermore, as argued by Wendy Garden, the colours used by Andrew are evocative of the colonial past, as red, white and blue, the main colours of the British and Australian flags are used32, thereby both referencing and challenging them.

What appealed to Andrew in Blandowski’s images was that “fantastic” element embedded in them33 ; he also wanted to ‘bring old and obscure images of indigenous people “into the light”’.34 Moreover, engaging with and reworking these images was a way for Andrew to ‘expose both the torment and the absurdity of Australia’s colonial past’.35Indeed, as mentioned by Jessica Neath, ‘he thrives on ambiguity and misinterpretation’ and likes to play with unsettling the colonial gaze by bringing attention to its construction. By using a ‘contemporary form of history painting’, his work The Island stands as ‘objects of evidence and of counter-memory’.36

Nicholas Thomas claims that Andrew’s work does not answer questions but stimulates people to ask them.37 While discussing with a woman who was troubled by the ceremony represented in The Island IV, Andrew explained how the work should be seen as a ‘theatre-style’ representation of this ceremony in a ‘hyper-real format’. Andrew and the visitor carried on discussing how these images are a ‘distortion of the truth’, a way to ‘implicate our belief in the fragments of history or give us some form of ownership of Blandowski’s accounts.38

Exposition Theme Park, 2008, installation de Brook Andrew au Museum of Contemporary Aboriginal Art, The Netherlands.

Numerous versions of The Island exist and are scattered in museums throughout the world, including Australia and the United Kingdom. Their acquisition by multiple and diverse institutions is evidence that museums and galleries dare to engage with works which disturb their colonial spaces. Nicholas Thomas talks of the ‘museum as method’, a place where ‘collection-based investigations’ can happen39, and a place that visitors and artists can make theirs through engaging with it.

Following Pierre Nora’s theory on lieux de mémoire40, we can consider not only the museum as a lieu de mémoire, but also the images themselves – both Andrew’s and Blandowski’s – as obvious ways of remembering. In this instance, one should consider Australia and The Island as being ‘legacy images’ as well as ‘powerful evidence, but also […] objects of memory’, ‘connect[ing …] photographic material to the continuing effects of dispossession’.41 In the light of works like The Island, Jessica Neath and Brook Andrew argue that museums should be considered as places for ‘inject[ing] new perspectives by hybridizing contemporary art with anthropological histories’.42 In so doing, Brook Andrew acts as an “ethnographer” in order to reveal these “legacy images”. 43

Clémentine Débrosse

Cover picture: photo montage of Brook Andrew's The Island I and William Blandowski's Plate 137: Aborigines of Australia: burial places near Budda in longitude 148° latitude 32° from a sketch by Capt. Sturt.by Clémentine Débrosse.

1 JORGENSEN, D., MCLEAN, I. (eds), 2017. Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art. Crawley (Western Australia), UWA Publishing, p. IX

2 NICHOLLS, C., 2003. “Brook Andrew: Seriously Playful”. RealTime 54, p. 28.

3 HUTCHENS In JORGENSEN, D., MCLEAN, I. (eds), 2017. Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art. Crawley (Western Australia), UWA Publishing, p. 308.

4 BUTLER, R., 2020. Framing the Voice/Voicing the Frame: On Brook Andrew’s Vox: Beyond Tasmania (2013). Index Journal 2 Law, p. 9.

5 ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 4.

6 Ibid, pp. 4-5.

7 Ibid, p. 6.

8 Ibid, p. 7.

9 Ibid.

10 ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 15.

THOMAS, N., 2011. “Von Hügel’s curiosity: Encounter and Experiment in the New Museum”. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 1 (1), p. 311.

11 ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 7.

12 Ibid, p. 16.

13 THOMAS, N., 2016. “The Collection as Creative Technology”. In The Return of Curiosity: What Museums Are Good for in the 21st London, Reaktion Book, p. 130.

14 ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 16.

15 Ibid, p. 17.

16 Ibid, p. 9.

17 HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, p. 11.

18 ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 15.

19 THOMAS, N., 2016. “The Collection as Creative Technology”. In The Return of Curiosity: What Museums Are Good for in the 21st London, Reaktion Book, p. 130.

HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, p. 9.

CARROLL, von Zinnenburg K., 2014. Art in the Time of Colony. Collection Empires and the Making of the Modern World, 1650-2000. New York, Routledge, pp. 152-153.

20 ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 11.

21 Ibid.

22 ANDREW, B., In ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 165.

23 THOMAS, N., 2016. “The Collection as Creative Technology”. In The Return of Curiosity: What Museums Are Good for in the 21st London, Reaktion Book, pp. 129-130.

GARDEN, W., 2011. “Ethical Witnessing and the Portrait Photograph: Brook Andrew”. Journal of Australian Studies 35 (2), p. 259.

24 HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, p. 10.

25 Ibid.

26 HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, p. 13.

27 Ibid, p. 14.

28 Ibid.

29 HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, p. 15.

30 ANDREW, B., In ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 167.

31 HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, pp. 15.

32 GARDEN, W., 2011. “Ethical Witnessing and the Portrait Photograph: Brook Andrew”. Journal of Australian Studies 35 (2), p. 261.

33 HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, pp. 2.

34 ANDREW, B., & NEATH, J., 2018. “Encounters with Legacy Images: Decolonising and Re-imagining Photographic Evidence from the Colonial Archive”. History of Photography 42 (3), p. 220.

35 HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, p. 2.

36 ANDREW, B., & NEATH, J., 2018. “Encounters with Legacy Images: Decolonising and Re-imagining Photographic Evidence from the Colonial Archive”. History of Photography 42 (3), p. 221.

37 THOMAS, N., 2011. “Von Hügel’s curiosity: Encounter and Experiment in the New Museum”. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 1 (1), p. 313.

38 ANDREW, B., In ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, p. 168.

39 THOMAS, N., 2016. “The Collection as Creative Technology”. In The Return of Curiosity: What Museums Are Good for in the 21st London, Reaktion Book, p. 116.

40 THOMAS, N., 2016. “The Collection as Creative Technology”. In The Return of Curiosity: What Museums Are Good for in the 21st London, Reaktion Book, p. 118.

41 ANDREW, B., & NEATH, J., 2018. “Encounters with Legacy Images: Decolonising and Re-imagining Photographic Evidence from the Colonial Archive”. History of Photography 42 (3), p. 217.

42 ANDREW, B., & NEATH, J., 2018. “Encounters with Legacy Images: Decolonising and Re-imagining Photographic Evidence from the Colonial Archive”. History of Photography 42 (3), p. 218.

43 FOSTER, H., 1995. “The Artist as Ethnographer?” In MARCUS, G. E., MYERS, F. R. (eds), The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology. Berkeley, University of California Press, pp. 302-309.

Bibliography:

- ALLEN, H. (ed), 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press.

- ANDREW, B., & NEATH, J., 2018. “Encounters with Legacy Images: Decolonising and Re-imagining Photographic Evidence from the Colonial Archive”. History of Photography 42 (3), pp. 217-238.

- BARRETT, J., & MILNER, J., 2014. Australian Artists in the Contemporary Museum. London, Routledge.

- BUTLER, R., 2020. Framing the Voice/Voicing the Frame: On Brook Andrew’s Vox: Beyond Tasmania (2013). Index Journal 2 Law, http://www.index-journal.org/issues/identity/framing-the-voice-voicing-the-frame-on-brook-andrews-vox-by-rex-butler

- CARROLL, von Zinnenburg K., 2014. Art in the Time of Colony. Collection Empires and the Making of the Modern World, 1650-2000. New York, Routledge.

- FOSTER, H., 1995. “The Artist as Ethnographer?” In MARCUS, G. E., MYERS, F. R. (eds), The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology. Berkeley, University of California Press, pp. 302-309.

- GARDEN, W., 2011. “Ethical Witnessing and the Portrait Photograph: Brook Andrew”. Journal of Australian Studies 35 (2), pp. 251-264.

- HECKENBERG, K., 2014. “Retrieving an Archive: Brook Andrew and William Blandowski’s Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen”. Journal of Art Historiography 11, pp. 1-18.

- JONES, C., 2018. “Brook Andrew – Rethinking Antipodes”. Art and Australia, https://www.artandaustralia.com/online/discursions/brook-andrew%E2%80%94rethinking-antipodes

- JORGENSEN, D., MCLEAN, I. (eds), 2017. Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art. Crawley (Western Australia), UWA Publishing.

- LYDON, J., 2012. The Flash of Recognition: Photography and the Emergence of Indigenous Rights. Sydney, NewSouth.

- NICHOLLS, C., 2003. “Brook Andrew: Seriously Playful”. RealTime 54, p. 28.

- THOMAS, N. & ANDREW, B., 2007. Brook Andrew The Island: A Contemporary Intervention in the Anthropological Archive. Cambridge, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- THOMAS, N., 2011. “Von Hügel’s curiosity: Encounter and Experiment in the New Museum”. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 1 (1), pp. 299-314.

- THOMAS, N., 2016. “The Collection as Creative Technology”. In The Return of Curiosity: What Museums Are Good for in the 21st London, Reaktion Book.

1 Comment so far