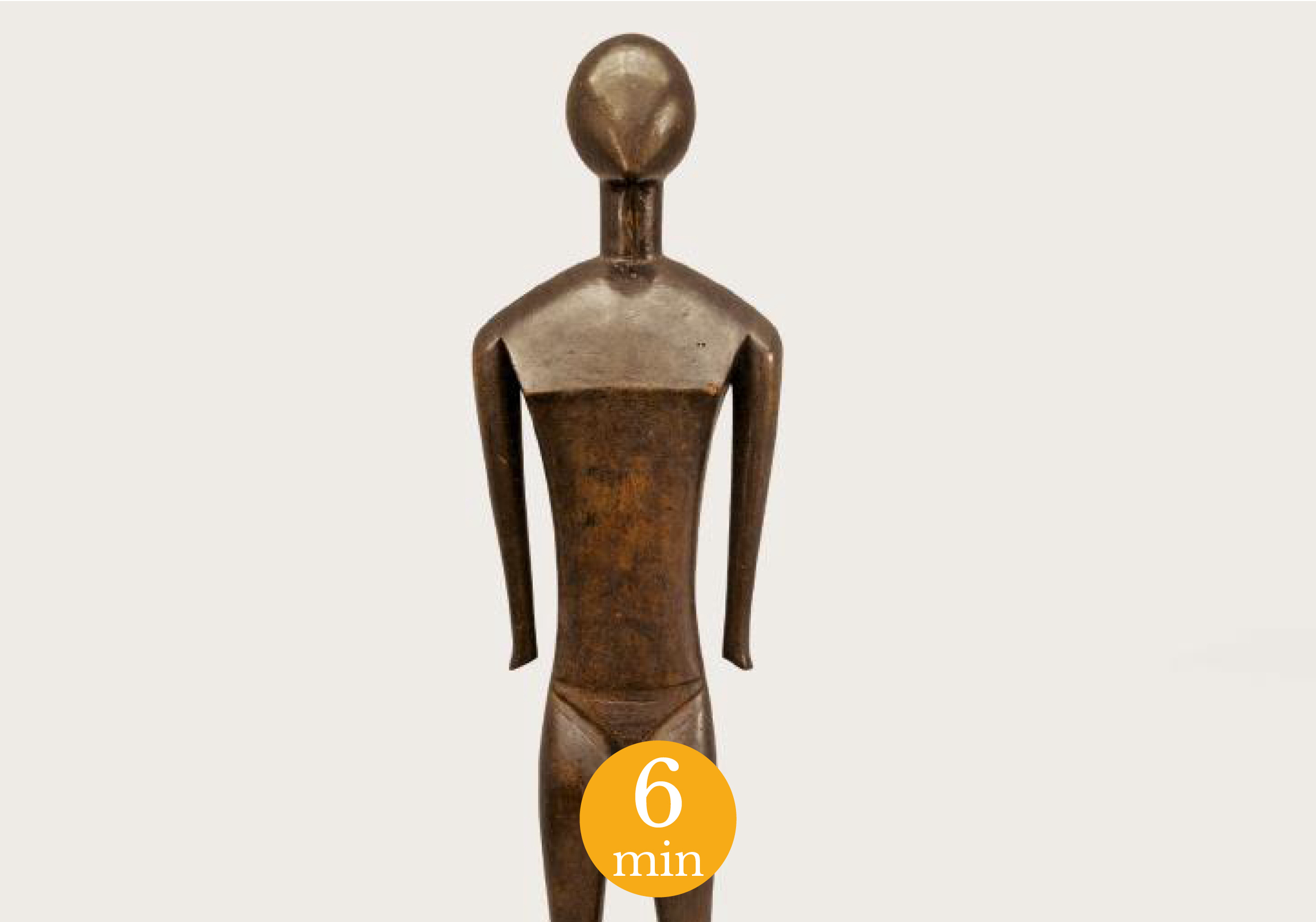

Among the key works in the famous George Ortiz Collection in Geneva, his figure of the deity Dinonga Eidu, a masterpiece of statuary from the small atoll of Nukuoro in Micronesia, stands out without question.

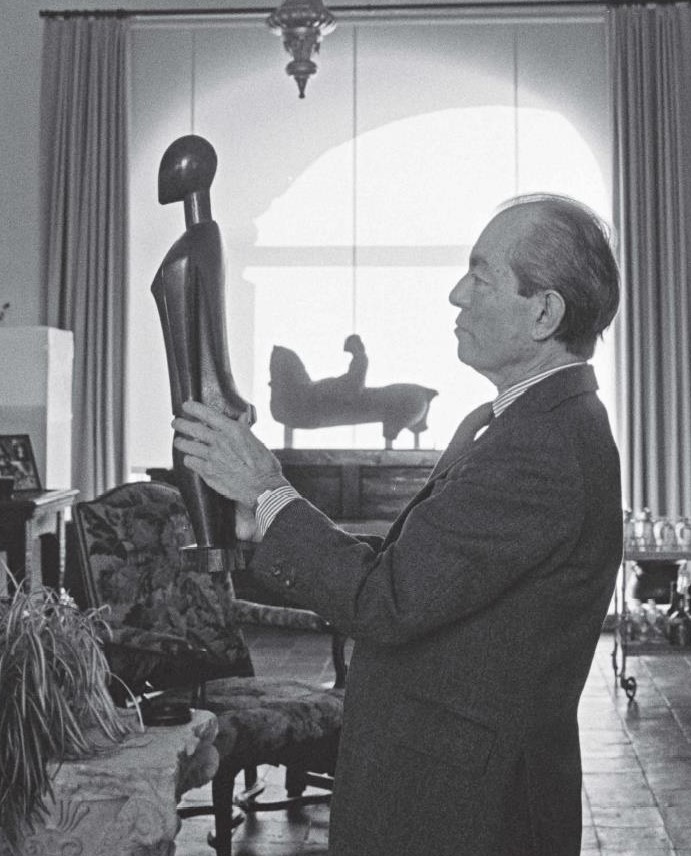

George Ortiz et sa statue Nukuoro. DR.

Acquired in 1867 by Lord and Lady Thomas Brassey during a voyage to the Pacific aboard the Sunbeam, it joined the Hastings Museum Collections in the United Kingdom from 1919 to 1958. After passing through the hands of James Hooper, Marie-Ange Ciolowska and Lance Entwistle, it joined the Ortiz Collection in 1986. Published in 1885 by Wright in the Catalogue Raisonné of the Natural History, Ethonographical Specimens and Curiosities Collected by Lady Brassey during the Voyages of the "Sumbeam", it is one of the rare witnesses to the enigmatic art of the Nukuoro Archipelago.

Historical context

The Carolinas are one of the four large archipelagos in Micronesia. As early as the 16th century, these territories were part of the voyages of the great navigators and were among the first visits by Westerners. To the north of the Carolinas, the Marianas, which were visited by Magellan in 1521, became a Spanish colony in 1564 and quickly became a stopover on the trade route to the Philippines. However, although these islands were in contact with the Western world very early on, the first evangelisation missions were systematic failures.

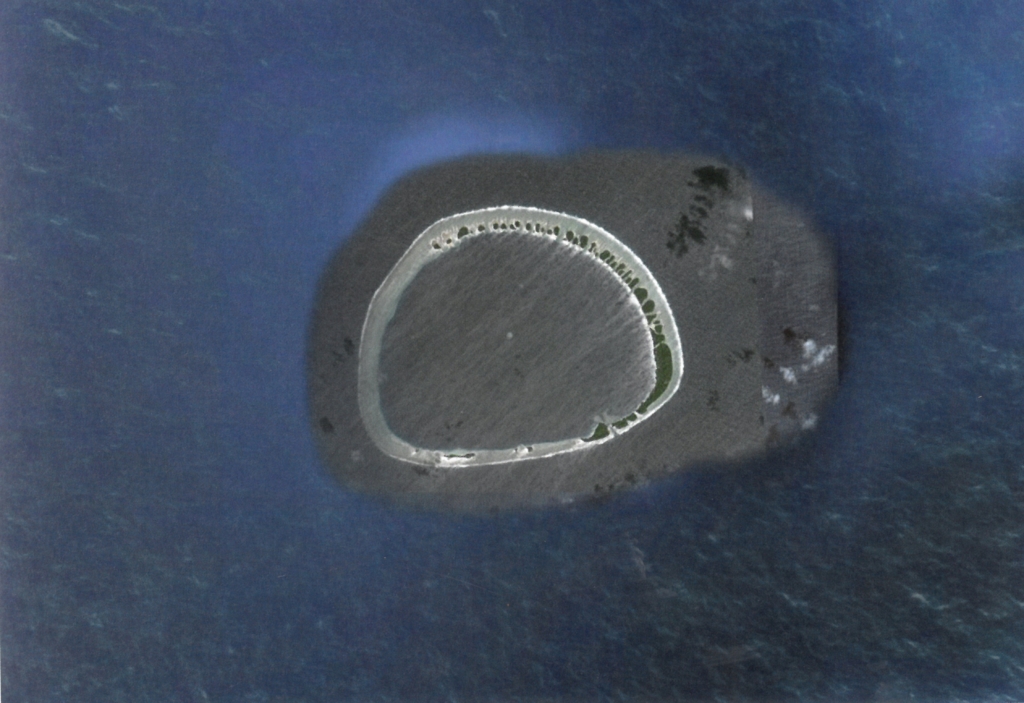

Aerial view of the Nukuoro Atoll showing the reef, the main island and the islets. Google Earth, image 2013.

Visited by a Spaniard in 1806, Nukuoro or Monteverde Island is one of the few Polynesian enclaves in the Carolinas. Its inhabitants are of Polynesian culture and speak a Polynesian language. Early accounts describe men of great beauty who were over six feet tall. Their behaviour is described as cheerful and friendly, despite the harshness and precariousness of life: some atolls, which consisted of only a narrow strip of land, were constantly confronted with the unpredictability of nature.

A. Krämer, 24 janvier 1910. Nukuoro village: road and principal houses. Hambourg, Ethnologie museum, photographic archive, inv. No. Krämer_SSE5_8670.

At the beginning of the 19th century, various sailors and ships stopped there and, in 1830, Captain Morrell was confronted with a difficult situation: the inhabitants, who had been friendly at first, quickly became aggressive and attacked the European sailors and missionaries who came to live on their island. However, the situation changed rapidly because soon after, on 15 September 1852, Reverends Doane and Sturges arrived in Ponape (an island near Nukuoro) to found the first Protestant mission. By February 1855, they returned to begin their mission, and towards the end of the year, on 24 December, they both left for Kosrae for a mission meeting, returning to Ponape on 11 January 1856. In October 1857, the king of Mac Askill, one of the islands surrounding Ponape north of Nukuoro, told Reverend Doane that he wanted a missionary to come and live on his island.

The above data provide important indications of the changing attitudes of the population as their religions were abandoned, which had a direct impact on their sculptural heritage. Kubary, a special envoy commissioned by the Godeffroy Museum in Hamburg to acquire works in the South Seas, made an initial short visit to Nukuoro in 1873 and then returned in 1877 for a longer stay to study the Caroline Islands and primarily Nukuoro. By this time, their religious practices had changed considerably as a European trader had been living permanently on the island since 1874.

Without specifying on which trip, Kubary reports in his diaries that he had someone buy two images on his behalf, one of which represented the goddess Ko Kawe, who was revered as a great idol in the Amalau. She was the consort of the god Te ariki and the patron goddess of the Sekawe, one of the five clans. Today we believe that all the deities reported by Kubary in Hamburg were probably collected during his second visit in 1877.

Representing the divine

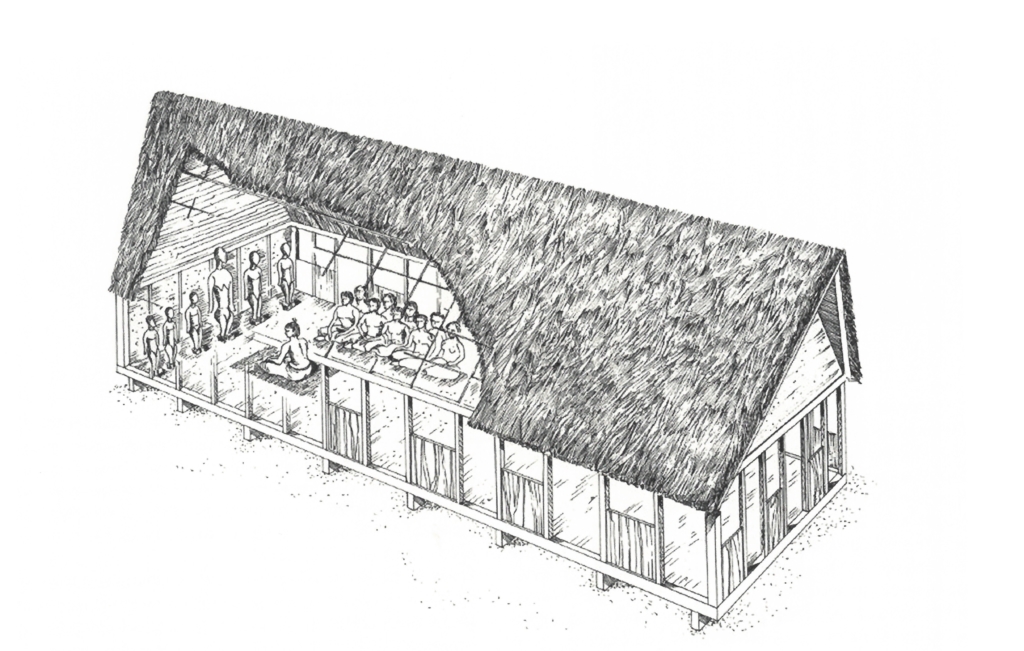

This statue is a representation of a venerated god or mythical ancestor. It was kept either with the main figure of the cult in the Amalau, the community's house of worship, or in one of the nine smaller houses of the gods.

Model of the Amalau temple made by Bernard de Grunne based on J.S. Kubary's description of a Takonota ceremony mentioned earlier. According to Kubary (1900), the Amalau temple is approximately 30 metres long. Drawing by Jean Funken.

The main figure of the cult was adorned with flowers, and was paraded on certain festivals, being offered a large number of offerings. Some of the smaller images were probably worshipped in the same way. Eilers reports that the main ritual of the worship of the gods was the draping of the tino in new clothes during the harvest. On this occasion, many cult ceremonies took place. The four iron nails inlaid on either side of the throat and under each buttock of this figure were probably added to this image, either to enrich it or to attach new clothes to it, obviously at a time when it was still worshipped. Iron nails may have been one of the earliest and most valuable objects exchanged or received during the passage of western ships.

A characteristic feature of these sculptures is the triangle ending in a prominent mons veneris representing the tattoo (te mata) that was compulsory for women. Such adornment was reserved for a small elite and associated with long religious ceremonies. This sculpture therefore represents the goddess Ko Kawe and is one of the earliest examples of this rare corpus.

A Nukuoro masterpiece

Comparison of three tino aitu figures from Houston seen from three quarters, Hamburg during the exhibition at Fondation Beyeler in 2013.

Through the purity of its sculpture and the fluidity of its lines, this work stands out as one of the most accomplished in his corpus of some thirty statues. The human body, entirely reinvented and stylised, is treated as a composition of abstract geometric forms. The perfect dialogue between the ovoid head and the various curved lines shaping the arms, torso and legs, testifies to the immense skill of the talented sculptor who created it. The monumentality of the work is due as much to the prominence of the negative spaces as to the perfectly controlled dynamics of the deep curves and tapered forms that delimit them. The masterly purity of its forms, the delicate curves of its contours and the beauty of its surface, devoid of any decoration, impose a striking modernity. Freed from the clothes and jewels that once adorned it, it now offers itself to our eyes in the purest perfection of its form.

In their study of the Nukuoro statuary, Christian Kaufmann and Oliver Wick assume that the first Nukuoro statue brought to Europe was the one acquired by Johann S. Kubary in 1873, closely followed by the one acquired by Edward Toppin Doane in 1874, now in the Bishop Museum in Honolulu (inv. no. 8151). The work from the George Ortiz Collection would thus be the third to join a Western collection, placing it in the most historical corpus of Nukuoro statuary, which is confirmed by its overall sculptural qualities. Exhibited by the Brassey couple at their home in Claremont on their return to the United Kingdom, it followed them to their home in Park Lane, London, in 1886 before joining the Hastings Museum Collections in 1919. In 1948 it was acquired, via an exchange, by the great collector James Hooper before joining the Parisian collection of Marie-Ange Ciolkowska in 1953 where it remained until the mid-1980s and its acquisition in 1985 by George Ortiz.

Nukuoro Dinonga Eidu figure, Nukuoro Island, Ponhpei State, Caroline Islands Archipelago, Federated States of Micronesia, wood from breadfruit tree (Artocarpus incisus), 18th-19th century, 40cm high. © Galerie Entwistle

Within his body of work, this work stands out for its almost unequalled degree of achievement. Although it does not have the dimensions of the largest Nukuoro figures, which can exceed two metres, it does not lose its monumentality. The hieratic nature of the sculpture, the anchoring of the massive legs in the ground and the breadth of the bulging torso masterfully convey the power of the divinity represented. However, while imposing this expressive force on his figure, the sculptor has not diminished its subtlety and sculptural finesse. Within the corpus, a large majority of the sculptures have their arms attached to the torso; the statue in the Ortiz Collection is one of those where the arms move away from the waist thanks to the elegant curve of the shoulders. This posture creates a strong contrast between the massiveness of the solid forms and the delicate empty spaces that outline the silhouette of the work, testifying to the perfection intended by the sculptor who created this work. Finally, the head of the sculpture stands out, an ovoid shape with a masterly purity sublimated by the shiny patina. The seat of the power of the divinity, this part of the body has concentrated the efforts of the artist who has succeeded in imposing the divine presence through this masterly technical prowess.

Alberto Giacometti, 1934-1935. Objet invisible (mains tenant le vide). DR.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Alberto Giacometti discovered the Nukuoro sculpture at the Musé de l'Homme in Paris given to him by Georges Henri Rivière. The visual shock was such that in 1934, inspired by this image, he created Objet invisible (hands holding the void), a work that asserts the same ethereal grace as the Nukuoro statuary. As for Henry Moore, he considered the Nukuoro figure in the British Museum (inv. no. 2968) to be one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of universal art. Thus, there are many examples of Western artists who have recognised the artistic importance of one of the rarest bodies of Oceanic art, which alone imposes the search for the absolute that has always guided mankind.

Pierre Mollfulleda

Cover picture: Nukuoro Dinonga Eidu figure, Nukuoro Island, Ponhpei State, Caroline Islands Archipelago, Federated States of Micronesia, wood from breadfruit tree (Artocarpus incisus), 18th-19th century, 40cm high. © Galerie Entwistle

Bibliography:

- KAUFMANN, C., WICK, O., 2013. Nukuoro, Sculptures from Micronesia. Munich, Hirmer.