In December 2013, the president of the New Guinea parliament, Theodore Zibang Zurenuoc, caused a stir in the country. Armed with an axe, he attacked the lintel adorning the parliament's frontispiece, irreversibly damaging the sculptures that adorned it. Although many voices were raised in Papua New Guinea to comment on this episode, not all of them were opposed to the president's actions, thus highlighting the debates that are shaking the country and its relationship with Christianity.

In order to understand this event, it is necessary to first look at the history of the parliament building and its décor. Designed by New Zealand architect Cecil Hogan and inaugurated in 1984, the Papua New Guinea parliament building takes the form of a haus tambaran, a typical building of the Abelam culture in the Sepik region. The building has an extensive interior and exterior decoration, largely created by the students of the National Art School under the direction of Archie Brennan. The façade is decorated with a large mosaic symbolising the country's resources and a carved lintel.1

Papua New Guinea Parliament's facade with the carved lintel still in place.

This lintel is reminiscent in form of the sculptures that usually decorate the facades of haus tambaran, but where Abelam lintels depict the faces of non-human entities involved in ritual life, the faces on the parliament lintel represent the nineteen provinces of Papua New Guinea. The purpose of the building and its decorative programme is thus to symbolise the unity and national identity of the newly independent country while recognising the importance of the different cultures that constitute it.2

It is precisely this decoration that Theodore Zurenuoc is attacking in 2013. In addition to the lintel, the president and his supporters also attacked a large sculpture inside the building entitled Bug Wantaim.3 Like the lintel, this work blends different sculptural traditions in the country and symbolises the need for collaboration between the different provinces through the institution of parliament. The president explains his action by the desire to purge the parliament of images that he considers to be linked to demonic figures and the practice of witchcraft.4

Papua New Guinea Parliament's façade after the degradation and removal of the carved lintel.

In other words, it is Christianity that is at stake here. While it may seem illegitimate in France to associate religious opinions with the décor of a public building, it must be understood that Papua New Guinea is not a secular state. The country's constitution (which can be consulted here) affirms from the outset the importance of the "Christian principles which are ours" and which are placed on an equal footing with the "noble traditions" inherited from the past.

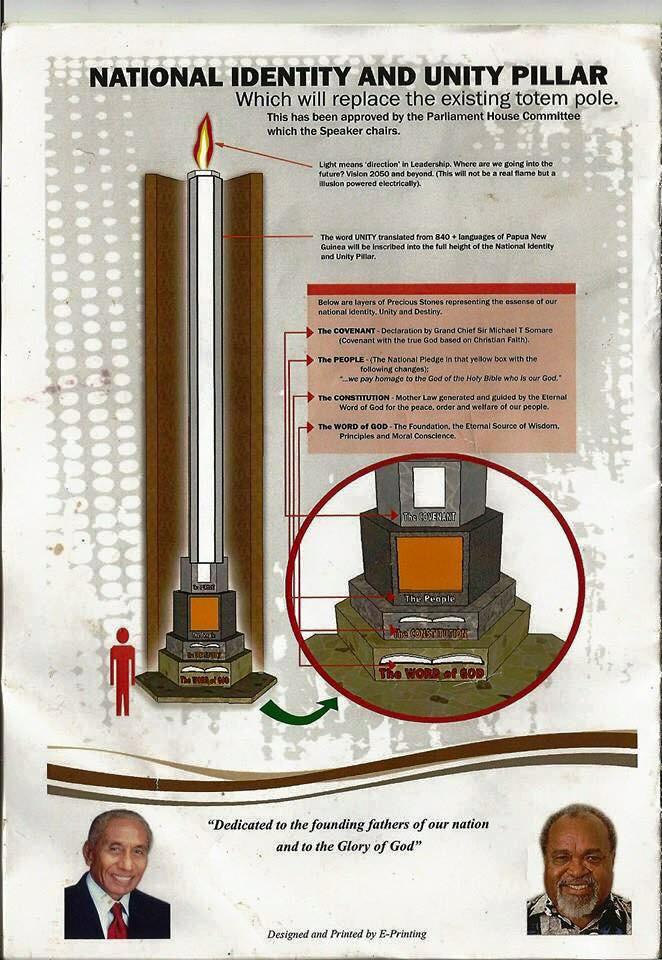

Theodore Zurenuoc presented his action as part of a project to reform and modernise the parliament and proposed to replace the sculptures with Christian symbols that would unify the country.5 The damaged sculptures were presented as "indecent"6, consisting of "idols" and "demonic masks".7 In their place, Zurenuoc proposed to install a "pillar of national identity and unity" whose first foundation would be the divine word (see illustration below).

Description of the Bug Wantaim sculpture according to Theodore Zurenuoc, the sculptures are described as immoral and linked to witchcraft 2014. "Reformation of National Parliament as a Symbol of National Unity" in Buisness Melanesia, May 2014.

Zurenuoc's project goes far beyond a simple interior decoration project, it is a real programme of moral reform of Papua New Guinea and its institutions that the president proposes to implement.8 He says that he wants to "inform the world that we are a Christian nation"9 and to fully base national unity and identity on Christianity.10

Theodore Zurenuoc's proposed pillar of national identity and unity 2014. "Reformation of National Parliament as a Symbol of National Unity" in Buisness Melanesia, May 2014.

However, this project is far from being unanimously supported in Papua New Guinea, despite the fact that Christianity is the national religion. The country's most important figures immediately spoke out against the abuse of the sculptures. Andrew Moutu, director of the National Museum, issued a statement (now unavailable online) saying that this action was illegal and "sacrilegious".11 The National Museum will recover what remains of the sculptures for safekeeping. The former Prime Minister, Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare, also strongly opposed the Speaker's move, which he described as "cultural terrorism".12 Even the National Bishops' Conference of Papua New Guinea and the Solomons condemned the destruction of the works and accused Zurenuoc of fundamentalism.13 .

Yet all these opponents are themselves Christians and adhere to the idea of Christianity as a state religion. What is at stake here are two very different views of Christianity. Although it is most often referred to in the Singular, Christianity is far from being a unified religion and a multitude of churches and currents coexist within it. Theodore Zurenuoc is close to the evangelical and Pentecostal currents that appeared within Protestantism from the end of the 18th century and which form a mosaic of churches in constant recomposition.

Evangelical-Pentecostal Christians in particular adhere to a very literal reading of the Bible and are oriented towards the expectation of the Last Judgement, which is seen as imminent. These churches often have a strong hostility to any practice or object that they perceive as being related to religions that preceded conversion to Christianity. Ancient religions are most often demonised and the entities involved in their cults associated with demons.14 In this context, the sculptures in the parliament appear to evangelical Christians as 'idols' because of their explicit link to certain ancient religious practices.

The project of moral reform of institutions advocated by Zurenuoc is also reminiscent of the theology of spiritual warfare often put forward by these churches, according to which believers are perpetually engaged in a struggle against demonic forces. This struggle is not only moral and spiritual but also physical and can be embodied in places. The parliament is thus perceived by Zurenuoc and his supporters as inhabited by evil forces, embodied and encouraged by the presence of the sculptures. The destruction of the sculptures is seen as a physical reclaiming of the building and a moral reclaiming of the institution it represents.

This view is not shared by the so-called mainline churches, principally the Catholic and Anglican churches. These churches, with a long history in the Pacific, often show a greater tendency to incorporate local practices into their worship. St Mary's Cathedral in Port Moresby, for example, is largely in the form of a haus tambaran. In their eyes, Zurenuoc's gesture appears to be contrary to the principles of Christianity: destroying the sculptures is tantamount to recognising their real spiritual power. The Catholic authorities denounced his gesture as a form of cargo cult.15

However, anthropologist John Barker, a specialist in Christianity in the Pacific, argues that Zurenuoc's project of moral reform is not sufficient to explain his action. Barker points out that the destruction of objects and buildings has been a feature of the conversion of Pacific peoples to Christianity.16 Contrary to popular belief, these destructions were often organised on the initiative of the converted populations, as the few missionaries were not in a position to impose them.

Barker proposes to link the destruction of the parliamentary sculptures with another event: the acquisition in 2015 by the Papua New Guinea government of a copy of the original edition of the King's James Bible (a translation of the Bible commissioned by King James I of England and first published in 1611). The object was welcomed with great pomp at Port Moresby airport and praised by Theodore Zurenuoc in a speech highlighting his plans for the moral reform of the country:

"We need morality more than anything else in this nation and you will understand that the Bible is the only source that contains these values more than any other faith document. If you want to fight corruption, if you want peace and if you want order and if you want discipline and if you want to fill the national nation with national patriotism then you had better teach morality."17

In the same way that the sculptures of parliament were presented as promoting the dysfunction of the parliamentary institution, John Barker points out that the King's James Bible appears here as an embodiment of moral values and compares it to a kind of new 'idol', this time positive. He points out that this is not the first time in Pacific history that Bibles as objects have been invested with such significance. Following the Polynesian conversions of the early 19th century, which were themselves marked by iconoclastic practices, the Bibles distributed by the missionaries were frequently considered as new objects of worship, invested with a force of change.19 The destruction of the sculptures of parliament, considered to be evil 'idols', was thus followed by the acquisition of a new idol, a Bible, on which to base a new social and moral order.20

However, Theodore Zurenuoc's project did not come to fruition, as in June 2016 the defacement and removal of the sculptures from parliament was ruled illegal by the National Court.21 Although the President was ordered to have the sculptures restored and reinstalled, the lintel has still not returned to the front of parliament.

Alice Bernadac

Featured Image: Parliament of Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby, Photo Tok Pisin English Dictionnary

1 ROSI, P., 1991. « Papua New Guinea’s Parliament House : A contested national symbol » in The Contemporary Pacific, vol. 3, n°2. Manoa, Centre for Pacific Islands Studies University of Hawaii Press. pp. 289-324.

2 ROSI, P., 1991. « Papua New Guinea’s Parliament House : A contested national symbol » in The Contemporary Pacific, vol. 3, n°2. Manoa, Centre for Pacific Islands Studies University of Hawaii Press. pp. 289-324. p. 290.

3 ROSI, P., 1991. « Papua New Guinea’s Parliament House : A contested national symbol » in The Contemporary Pacific, vol. 3, n°2. Manoa, Centre for Pacific Islands Studies University of Hawaii Press. pp. 289-324. p. 303.

4EVES, R., HALEY, N., et al. 2014. Purging Parliament : A New Christian Politics in Papua New Guinea ?, SSEGM Discussion Paper 2014/1. Canberra, Australia National University. p. 5.

5 2014. « Reformation of National Parliament as a Symbol of National Unity » in Buisness Melanesia, mai 2014. (consultable here)

6 2014. « PNG Speaker Clarifies Parliament Restoration and Unity Project » in Buisness Melanesia, avril 2014. (consultable here)

7 EVES, R., HALEY, N., et al. 2014. Purging Parliament : A New Christian Politics in Papua New Guinea ?, SSEGM Discussion Paper 2014/1. Canberra, Australia National University. p. 4.

8 COX, J., 2014. « The Beginnings of a ‘Pentecostalist’ Public Realm in Papua New Guinea ? » in EVES, R., HALEY, N., et al. 2014. Purging Parliament : A New Christian Politics in Papua New Guinea ?, SSEGM Discussion Paper 2014/1. Canberra, Australia National University. pp. 11-14 : p. 13.

9 2014. « PNG Speaker Clarifies Parliament Restoration and Unity Project » in Buisness Melanesia, avril 2014. (consultable here)

10 2014. « Reformation of National Parliament as a Symbol of National Unity » in Buisness Melanesia, mai 2014. (consultable here)

11 ISAACS, J & SMITH, T., et al., 1998. Emily Kame Kngwarreye Paintings. Sydney, Craftman House. p. 61.

12 MAY, R., 2014. « The ‘Zurenuoc Affair’ : Religious Fondamentalism and National Identiy ? » in EVES, R., HALEY, N., et al. 2014. Purging Parliament : A New Christian Politics in Papua New Guinea ?, SSEGM Discussion Paper 2014/1. Canberra, Australia National University. pp. 3-8.

13 MAY, R., 2014. « The ‘Zurenuoc Affair’ : Religious Fondamentalism and National Identiy ? » in EVES, R., HALEY, N., et al. 2014. Purging Parliament : A New Christian Politics in Papua New Guinea ?, SSEGM Discussion Paper 2014/1. Canberra, Australia National University. pp. 3-8.

14 Pour plus d’informations sur les églises évangélistes, pentecôtistes et leur histoire on pourra consulter COLEMAN, S & HACKETT, R. (éds.), 2015. The Anthropology of Global Pentecotalism

and Evangelicalism. New York, New York University Press.

15 BARKER, J., 2017. « The politic of salvation in Papua New Guinea : Thoughs on the Parliamentary Iconoclasm of 2013 », intervention lors du séminaire FRAO, EHESS, 03/05/2017.

16 BARKER, J., 2017. « The politic of salvation in Papua New Guinea : Thoughs on the Parliamentary Iconoclasm of 2013 », intervention lors du séminaire FRAO, EHESS, 03/05/2017.

17 2015. « King James Bible arrives in Port Moresby », reportage d’EMTV. (consultable ici)

18BARKER, J., 2017. « The politic of salvation in Papua New Guinea : Thoughs on the Parliamentary Iconoclasm of 2013 », intervention lors du séminaire FRAO, EHESS, 03/05/2017.

19 SISSONS, J., 2014. The Polynesian Iconoclasm : Religious Revolution and the Seasonality of Power. New York, Berghahn.

20 BARKER, J., 2017. « The politic of salvation in Papua New Guinea : Thoughs on the Parliamentary Iconoclasm of 2013 », intervention lors du séminaire FRAO, EHESS, 03/05/2017.

Bibliography:

- BARKER, J., 2017. « The politic of salvation in Papua New Guinea : Thoughs on the Parliamentary Iconoclasm of 2013 », intervention lors du séminaire FRAO, EHESS, 03/05/2017.

- EVES, R., HALEY, N., et al. 2014. Purging Parliament : A New Christian Politics in Papua New Guinea ?, SSEGM Discussion Paper 2014/1. Canberra, Australia National University. (consultable ici)

- MOUTU, A., 2013. « Museum decries removal of lintel on the National Parliament », communiqué de presse du 28 novembre 2013. (Précédemment consultable here)

- ROSI, P., 1991. « Papua New Guinea’s Parliament House : A contested national symbol » in The Contemporary Pacific, vol. 3, n°2. Manoa, Centre for Pacific Islands Studies University of Hawaii Press. pp. 289-324.

- SISSONS, J., 2014. The Polynesian Iconoclasm : Religious Revolution and the Seasonality of Power. New York, Berghahn.

- TOMLINSON, M & McDOUGALL, D (éds.)., 2013. Christian Politics in Oceania. New York, Oxford, Berghahn Books.

- 2014. « PNG Speaker Clarifies Parliament Restoration and Unity Project » in Buisness Melanesia, avril 2014. (consultable here)

- 2014. « Reformation of National Parliament as a Symbol of National Unity » in Buisness Melanesia, mai 2014. (consultable here)

- 2015. « King James Bible arrives in Port Moresby », reportage d’EMTV. (consultable ici)