After the crushing of the Paris Commune insurrection, 4,500 Communards were deported to New Caledonia, including 25 women.1 Among them was Louise Michel who was charged with seven counts: "1 - attack with the aim of changing the government; 2 - incitement to civil war; 3 - carrying visible weapons and military uniform; use of her weapons; 4 - forgery; 5 - use of forgeries; 6 - complicity, by provocation and machination, in the assassination of people held, supposedly, as hostages by the Commune; 7 - complicity in illegal arrests, followed by torture and death"2 (the Council of War would, however, only retain charge number 3). In August 1873, after twenty months in the Auberive Abbey prison (Haute-Marne), she was embarked for New Caledonia. During the four months of the voyage, Louise Michel, until then a Blanquist socialist3, was converted to anarchist theses4 by Nathalie Lemel (1827-1921)5, another leading figure in the Paris Commune. On 14 December 1873, they disembarked at the Ducos peninsula, dedicated to deportation in a fortified enclosure, where they shared the same cabin.

Left: Portrait of Nathalie Lemel, unknown author, before 1921. Right: Louise Michel in federate uniform, Fontange photograph, 1871. © musée de l’Histoire vivante de MontreuilLiving with the whole country

During the seven years she spent on the rock, Louise Michel showed a great curiosity for everything around her. She read, sought information, observed, collected, wrote and drew. Her intellectual activities contrasted with those of the other Communard deportees, most of whose written work dealt with the events of the Commune or the treatment they received in the prisons.6 Conversely, Louise Michel turned away from the metropolis and was "living with the entire [Kanak] country".7 She was even commissioned by the French Botanical Society, which was interested in her discoveries, particularly about edible plants.8 Necessarily, she came to collaborate with the people with the most detailed knowledge of the local flora: the Kanak. For the Kanak activist Marie-Claude Tjibaou9, Louise Michel "immediately perceived this communion between the Kanak and nature and was able to translate it into her texts".10 It is interesting to note that, in contrast, the Communard deportees were city dwellers, unaccustomed to a rural environment and totally alien to the tropical environment.

Prisons flower, drawing of a branch of ivy, graphite drawing, 12.5 x 8.5 cm, Louise Michel, Arras prison, 1871. © Gallica, BnF

However, contacts between Kanak and deportees remained very limited. During the period of detention in the fortified enclosure, they were limited almost exclusively to brief commercial exchanges when Kanak merchants came to sell certain basic products on the peninsula. One of these merchants, Daoumi, from Lifou, spoke a little French and made friends with Louise Michel. It was through him that she began to discover the Kanak culture.11

« Est-ce que ce ne sont point nos frères ? » : soutenir la lutte en territoire colonisé

Louise Michel is certainly imbued with the stereotypes of her time, easily detectable in the racist vocabulary she uses to refer to Kanak people, in her evolutionary12 approach to their culture or in the sometimes infantilising and meddlesome way she conceives of the pseudo civilising mission of whites towards them. She believes, like most commentators of the late 19th century, that "a Western education [can] 'save' the Kanak, whom she often describes as children capable of learning quickly".13 However, she was very critical of traditional European education and had made it one of her battles during the Paris Commune, advocating and implementing universal education for girls and boys - which was highly innovative at the time.14 This remained one of her concerns during her stay in New Caledonia:

"On the Ducos peninsula, she started to open a school once a week for Kanak children which provoked the anger of the French authorities who asked her to stop. Louise Michel tried for a few months to continue in the bush.15

While she was not without prejudices about her Kanak neighbours, Louise Michel was respectfully curious about them and recognised the legitimacy of their struggles. She was "so critical of the dominant French culture and bourgeois society, of gender and class relations"16 that she came to question certain stereotypes and look at her surroundings with an understanding eye. The American historian Carolyn Eichner, associate professor in the Department of History and Gender Studies at the University of Milwaukee and author of Surmounting the Barricades: Women in the Paris Commune17, believes that Louise Michel's feminist commitment may also have led her to question the relations of domination within the New Caledonian colony:

« Il y a du féminisme dans sa manière de dénoncer l’oppression des Français sur les Kanak qu’ils perçoivent alors comme leur propriété. Son féminisme était, il faut le rappeler, un féminisme anarchiste. Son féminisme était ce qu’on appellerait aujourd’hui intersectionnel au sens où elle ne regardait pas seulement le genre, mais également les manières dont il s’articule avec la race et la classe. »18

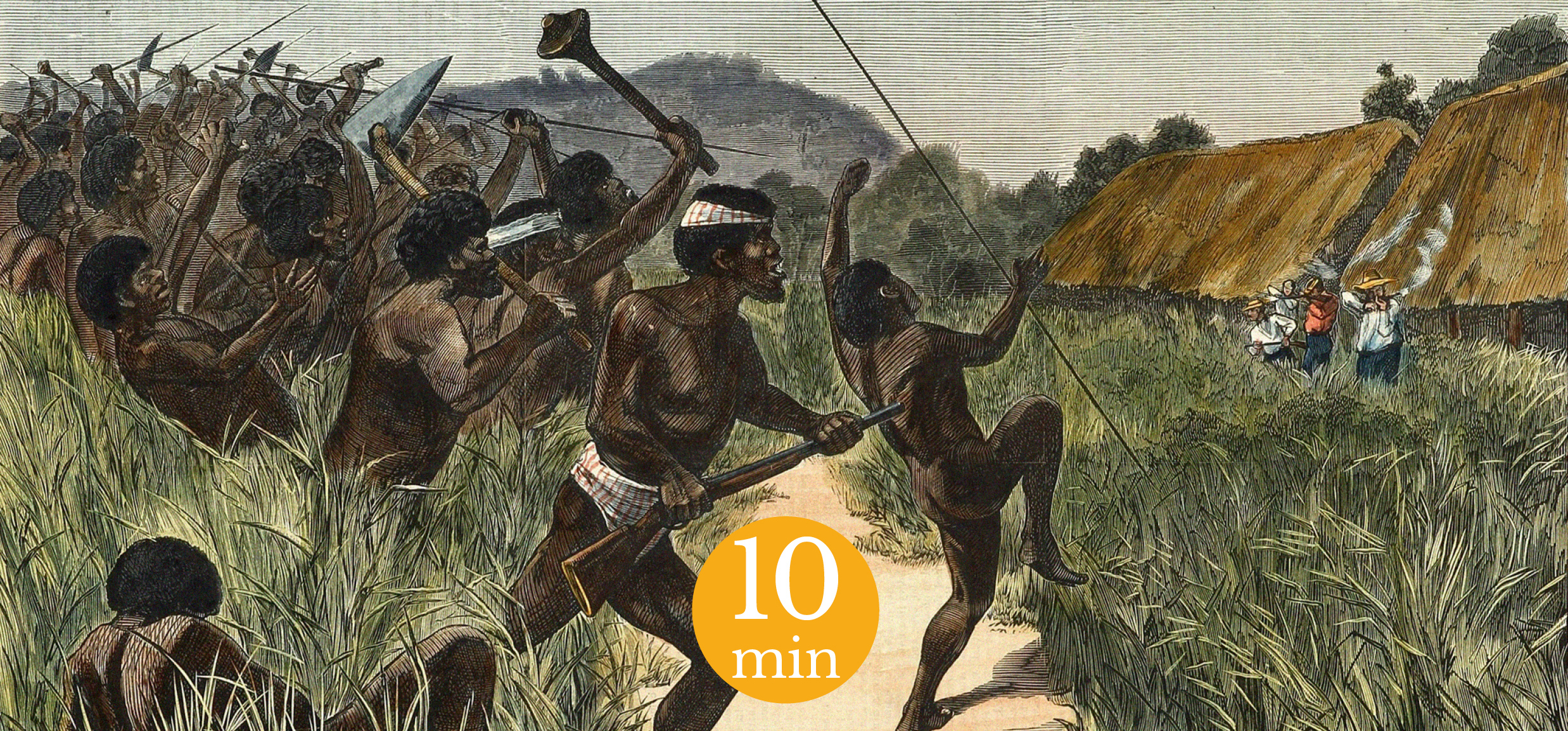

Aussi Louise Michel est-elle l’une des rares, parmi les déportés de la Commune, à prendre fermement le parti des rebelles kanak lors de la grande Insurrection de 1878 :

"Among the deportees, some sided with the Canaques, others against. For my part, I was absolutely for them. This led to such discussions between us that one day, at the West Bay, the whole [surveillance] post came down to see what was happening. There were only two of us shouting like thirty."19

As we developed in the first article of this series, few Communards were really hostile to the colonial project and even fewer granted the colonised Kanaks the ideals of self-determination that they dreamed of for themselves. Louise Michel was moved by this inconsistency:

"How are you not with them, you victims of reaction, you who suffer oppression and injustice! Are they not our brothers? They too were fighting for their independence, for their lives, for freedom. I am with them, as I was with the people of Paris, revolted, crushed and defeated."20

Et de souligner le caractère profondément déséquilibrés des combats de 1878 :

"On the Canaque side, with slingshots, assegais, puzzles; on the White side, with mountain howitzers, rifles, all the weapons of Europe."21

Dans ses mémoires sur la Commune, Louise Michel raconte comment elle fit le lien, symboliquement, entre ses engagements militants dans la Commune de Paris et les revendications des rebelles kanak :

"During the Canaque insurrection, on a stormy night, I heard a knock on the door of my hut compartment. Who is there?" I asked. - Taïau," was the reply. I recognised the voice of our Canaque food bringers (taïau means friend). It was them, indeed; they had come to say goodbye to me before they swam away through the storm to join their own people, to beat the evil whites, they said. So this red scarf of the Commune that I had kept through a thousand difficulties, I divided it in two and gave it to them as a souvenir."22

Faisant, à de multiples reprises, le parallèle entre la lutte kanak et la lutte communarde qui avait eu lieu sept ans plus tôt, Louise Michel reconnait comme légitimes la protestation contre les spoliations foncières et la volonté d’autodétermination des insurgés de 1878. Soulignons que c’est une position très minoritaire, non seulement chez les déportés de la Commune nous l’avons vu, mais de manière plus générale dans la société française dans son ensemble :

« Personne dans la gauche française n’était vraiment contre la colonisation à cette époque. […] Elle est l’une des premières à avoir manifesté une opposition au projet impérialiste, notamment à travers ce qu’elle voyait en Nouvelle-Calédonie. Elle s’est fait là-bas le témoin des exactions contre les Kanak, mais aussi de l’attaque en règle contre leur culture, dont elle a très tôt eu la conscience de la possible disparition. »23

The Canaque Legends of Louise Michel

An outraged witness to the ethnocide that was taking place in New Caledonia at the end of the 19th century, and "particularly interested in the orality of Kanak culture, at a time when the French generally despised oral cultures"24, Louise Michel set out to collect it. This provided her with the raw material for her collection of Kanak tales. Or rather her collections, because the Canaques Legends are actually two editions ten years apart, quite different in content, intention and scope.

Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques was published in 1875, just two years after Louise Michel's arrival in New Caledonia. The collection (fifteen texts: an introduction by the author and fourteen legends) was initially published in the form of serials in issues 73 to 84 of the anticlerical weekly Les Petites Affiches de la Nouvelle-Calédonie, a journal of maritime, commercial and agricultural interests published every Wednesday.

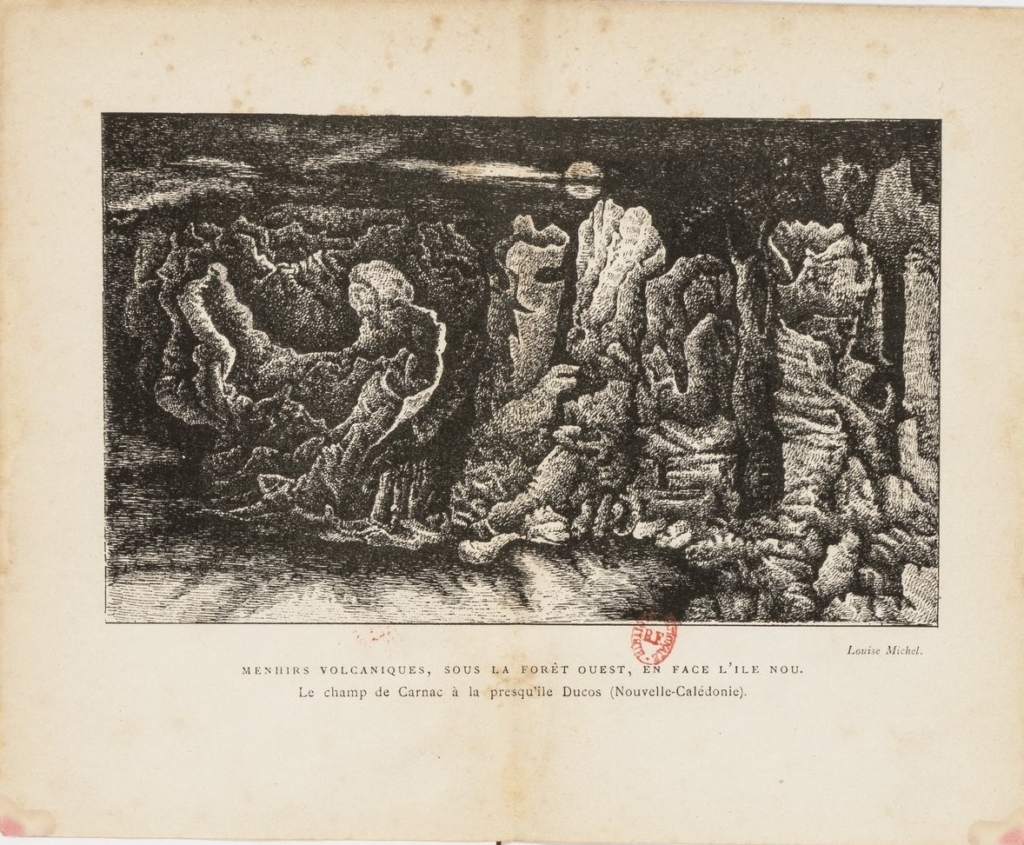

Légendes et chants de gestes canaques25 was published in Paris in 1885 and contains twenty-four texts (some unpublished, others extensively revised), four drawings by Louise Michel, eight lists of vocabularies and numbering in Kanak languages, four "reflections" on music, medicine and Kanak "aptitudes".26

Title page of the first edition of Légendes et chants de gestes canaques, Kéva et cie Éditeurs, Paris, 1885. © Gallica, BnF

At the time of the prison, there were twenty-eight languages spoken in New Caledonia.27 Although she did not learn any of them, Louis Michel compiled a glossary from several of these languages. A glossary that is certainly not linguistically accurate, but which 'nonetheless represents a fine tribute' for Marie-Claude Tjibaou.28 In addition to the Kanak languages, Bishlamar, a Melanesian pidgin, was a great source of enthusiasm for Louise Michel:

« C’était un merveilleux exemple de ce que pouvait être une langue universelle. Le bichelamar était parlé par les Kanak en lien avec les commerçants étrangers, mais était aussi parfois utilisé pour communiquer entre différents groupes qui n’avaient pas la même langue. »29

And indeed, the dream of a universal language which would allow "peoples to overcome their national identities and to fraternise"30, was common to many anarchists at the end of the 19th century. This was the time when vehicular31 languages such as Esperanto were created in Europe.

Volcanic menhirs, after a drawing by Louise Michel, Kéva et cie Éditeurs, Paris, 1885. © Gallica, BnF

Through the variety of media present in this second edition of her Légendes, Louise Michel "welcomes the Other in a more manifold way" and this "in a dynamic of commitment".32 For good reason: during the ten years between these two publications Daoumi died and Louise Michel changed informants (1876-77), the Kanak Insurrection broke out and was put down in bloodshed (1878) and Louise Michel, having received amnesty, returned to Paris (1880).33 She was a different woman when she returned to metropolitan France. During her years of exile, she developed an ideology that we would describe today as ""anti-imperialist", although of course it is difficult to use our current standards on such a subject".34

The legend at work for history

A tribute to Kanak languages and culture, the tales collected by Louise Michel are also intended to be an introduction to this culture for Europeans. The author did not aim for ethnographic accuracy, but adapted the material collected to her readership (the "friends of Europe", to whom the 1875 edition is dedicated). She thus watered down the tales to remove sexual or scatological elements that might offend European mores. Similarly, the 1885 tales, unlike those published ten years earlier, feature "strong, powerful, independent women".35 Carolyn Eicher analyses this strengthening of female roles as serving the Kanak cause:

« On peut bien sûr y voir une lecture féministe, mais aussi le fait qu’elle voulait montrer aux Français que les Kanak étaient beaucoup plus civilisés qu’ils ne le pensaient et que ne l’étaient les Français eux-mêmes. »36

Of course, Louise Michel's interpretative biases are numerous, giving these legends and songs a hybrid character, halfway between documentary testimony and an exercise in literary creation. Louise Michel got her sources from only three main informants, Daoumi and his brother, and Charles Malato, with whom she communicated in French, since she had no command of either Kanak or Pidgin languages. As a prisoner for most of her stay in New Caledonia, she probably did not directly attend the high points of Kanak life, but was able to see certain representations of it during dances mimicking war, fishing, etc.37 Above all, she did not have the keys to understanding certain central elements of Kanak society, such as the systems of exchange (of goods and women) and the modes of interaction between tribes. For all these reasons, "her testimony is of little value and, for example, the place given to women is the result of her generosity".38 It is indeed difficult "to make comparisons between Europe and Oceania on the basis of non-overlapping notions of gender".39

So how much of this body of work is Kanak and how much is Communard? For nearly ten years, between 1875 and 1885, Louise Michel cut, pasted and recomposed. This is part of her very creative process, rewriting being a process she uses in most of her works.40 In the case of the Légendes, this lends itself all the more to the fact that she uses, "in a written form, a plasticity specific to the tale and the orality of popular narration"41:

« Elle a raconté plus tard dans ses Mémoires comment ces contes lui rappelaient les veillées de paysannes où s’échangeaient toujours les mêmes histoires avec des ajouts, des nuances sans cesse renouvelées. »42

From this elastic raw material of oral culture, Louise Michel sought to present her own interpretation of the richness of Kanak culture, based on the friendly relations she had maintained with its representatives and on her conviction of the legitimacy of their claims. The example of the place she gives to women in her tales is significant in this respect:

"In her memoirs, Louise Michel described Kanak society as extremely misogynistic. She recalls, for example, that the word for 'woman' is the same as for 'nothing'. But it is noticeable that, in what she published in France, there is nothing about the violence suffered by Kanak women. [This led her to represent the Kanak to the French as a culture where women had value, at a time when the status of women was often used to classify 'civilisations'".43

According to Carolyn Eichner, we can read the beginnings of Louise Michel's anti-colonialist commitment through the tales she has collected.44 She does not seek scientific accuracy but seeks to expose her truth, the sensitive truth of an eternal insurgent against injustice. She bears witness to her stay in New Caledonia with "the breath of romanticism against the spirit of the Enlightenment".45 As Marie-Claude Tjibaou summarises:

"Her approach may be intuitive, but it certainly shows great sensitivity. She knows how to take the time needed to get to know and understand the people around her. She also knows how to love them beyond differences, appearances and especially prejudices. [She has [...] some rightness".

Louise Michel's Kanak legacy

Refusing the individual pardons and other preferential treatments offered to her by an anxious French government not to make a martyr of this very popular figure46, Louise Michel remained in New Caledonia until the general amnesty of the Communards voted in 1880. When she arrived in Paris on 9 September, 20,000 people were waiting for her and cheered her on at the Gare Saint-Lazare.47 In New Caledonia, her legacy was for a time obscured. Marie-Claude Tjibaou recalls that it was not taught to people of her generation:

« Peut-être aurait-elle marqué davantage l’histoire si elle avait traduit sa révolte par la violence plutôt que par son intérêt pour les gens d’ici. Il est vrai que l’on n’a jamais parlé dans ce pays des gens qui étaient proches des Kanak et qui témoignaient de leurs valeurs. Au contraire, on les a occultés. On a préféré mettre en exergue nos révoltes plutôt que les sentiments d’estime que nous inspirions… »48

Today however, she is an esteemed figure in Kanak history, particularly because of her involvement with the insurgents during the 1878 revolt. Although she was long ignored, she is now fully part of this history.49 In 2005, for the centenary of her death, the Tjibaou cultural centre in Nouméa paid her a special tribute in an exhibition on the exiled communards. Perhaps a post-mortem way of keeping the promise she made from the boat that took her away from the rock forever, when she shouted "I'll be back".

Margot Duband

Cover picture: Native Revolt at New Caledonia, Julian Rossi Ashton, 1878.

To go further, read: Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques, republié en 2006 aux Presses universitaires de Lyon : MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875)Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon.

1 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

2TCHERNOOKOV, J., 2018. « Louise Michel, une femme libre au bagne ». Le Blog Gallica, 20 août 2018. https://gallica.bnf.fr/blog/20082018/louise-michel-une-femme-libre-au-bagne,dernière consultation le 28 mars 2022.

3 A doctrine of political action named after Auguste Blanqui who believed that the people should be led to revolution by a small group of organised and armed revolutionaries, giving impetus to the revolt.

4 Ensemble de théories et de pratiques anti-autoritaires basées sur la démocratie directe et ayant la liberté individuelle comme valeur fondamentale.

5 Militante de l’Association internationale des travailleurs et féministe, elle se bat dans les années 1860 pour la parité des salaires entre hommes et femmes. Elle est à l’origine de coopératives alimentaires et de restaurants ouvriers. Elle participe à la Commune de Paris au sein de l’Union des femmes pour la défense de Paris et les soins aux blessés, dont elle fait partie du comité central.

6 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 24.

7 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 8.

8 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

9 Born in 1949, Marie-Claude Tjibaou is a Kanak politician committed to improving the living conditions of the Kanak people and an activist for the defence of Melanesian culture. She is the widow of the independence leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou.

10 Marie-Claude Tjibaou in MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 9.

11 DELAPORTE, L., 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

12 19th century anthropological theory postulating a linear mode of evolution of societies, based on the unique model of the development of Western society.

13 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

14 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

15 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

16 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

17 « Surmonter les barricades : les femmes dans le Commune de Paris ».

18 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

19 MICHEL, L, 2015 [1889]. La Commune. Paris, La Découverte.

20 BARONNET, J. et CHALOU, J.,1987. Les Communards en Nouvelle-Calédonie. Histoire de la déportation. Paris, Mercure de France, p. 321.

21 MICHEL, L, 2015 [1889]. La Commune. Paris, La Découverte.

22 MICHEL, L, 2015 [1889]. La Commune. Paris, La Découverte.

23 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

24 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

25 Le terme « chansons » est remplacé dans le titre par celui de « chants », plus fidèle selon elle au caractère « lyrique et noble » de ces contes.

DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

26 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 16.

27 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

28 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 9.

29 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

30 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022

31 A vehicular language is a third language used as a means of communication between populations with different mother tongues.

32 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 15.

33 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 15.

34 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

35 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

36 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

37 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 25.

38 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 25.

39 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 26.

40 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 17.

41 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 11.

42 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

43 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

44 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

45 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 19.

46 DELAPORTE, L, 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

47 TCHERNOOKOV, J., 2018. « Louise Michel, une femme libre au bagne ». Le Blog Gallica, 20 août 2018. https://gallica.bnf.fr/blog/20082018/louise-michel-une-femme-libre-au-bagne, dernière consultation le 28 mars 2022.

48 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 8.

49 MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, p. 8.

Bibliography:

- BALLAST, 2021. « Louise Michel : tenir la lutte en pays colonisé ». Revue Ballast, 25 mars 2021. https://www.revue-ballast.fr/louise-michel-colonise/, dernière consultation le 28 mars 2022.

- BARBANÇON, L., 2003. L’Archipel des forçats : Histoire du bagne de Nouvelle-Calédonie (1863-1931). Villeneuve d’Ascq, Presses universitaires du Septentrion.

- BARONNET, J. et CHALOU, J.,1987. Les Communards en Nouvelle-Calédonie. Histoire de la déportation. Paris, Mercure de France.

- DELAPORTE, L., 2018a. « Quand la France choisit de « vomir ses criminels » en Nouvelle-Calédonie ». Médiapart, 15 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/150818/quand-la-france-choisit-de-vomir-ses-criminels-en-nouvelle-caledonie, dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- DELAPORTE, L., 2018b. « Déportés en Nouvelle-Calédonie: l’improbable rencontre des communards et des insurgés algériens ». Médiapart, 19 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/190818/deportes-en-nouvelle-caledonie-l-improbable-rencontre-des-communards-et-des-insurges-algeriens, dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- DELAPORTE, L., 2018c. « Kanak et déportés: le rendez-vous manqué ». Médiapart, 21 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/210818/kanak-et-deportes-le-rendez-vous-manque, dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- DELAPORTE, L., 2018d. « Louise Michel et les Kanak: amorce d’une réflexion anti-impérialiste ». Médiapart, 23 août 2018. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/230818/louise-michel-et-les-kanak-amorce-d-une-reflexion-anti-imperialiste, dernière consultation le 30 mars 2022.

- DOTTE, E., 2017. « How Dare Our ‘Prehistoric’ Have a Prehistory of Their Own?! The interplay of historical and biographical contexts in early French archaeology of the Pacific », Journal of Pacific Archaeology 8 (1), pp. 25-34.

- DROZ, B., 2009. « Insurrection de 1871 : la révolte de Mokrani », in L’Algérie et la France. Paris, Robert Laffont, pp. 474-475.

- DUBAND, M., 2016. La mission archéologique et ethnographique en Nouvelle-Calédonie de Marius Archambault (1898-1920). Paris, mémoire d’étude de l’école du Louvre.

- DUBAND, M., 2019. « 1878 : deux regards sur l’Histoire ». CASOAR, https://casoar.org/2019/10/30/1878-deux-regards-sur-lhistoire/, dernière consultation le 27 novembre 2021.

- MAYER, S., 1880. Souvenirs d’un déporté, étapes d’un forçat politique. Paris, E. Dentu Editeur.

- MICHEL, L., 2000 [1904]. Histoire de ma vie : seconde et troisième parties. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon.

- MICHEL, L., 2015 [1889]. La Commune. Paris, La Découverte.

- MICHEL, L. et BOGLIOLO, F., 2006. Légendes et chansons de gestes canaques (1875) Suivi de Légendes et chants de gestes canaques (1885) et de Civilisation. Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon.

- SAT, B., 2021. « 150ème anniversaire de la Commune : Louise Michel, une déportée pas comme les autres ». Nouvelle-Calédonie 1ere, 19 mars 2021. https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/province-sud/150eme-anniversaire-de-la-commune-louise-michel-une-deportee-pas-comme-les-autres-962752.html, dernière consultation le 29 mars 2022.

- TCHERNOOKOV, J., 2018. « Louise Michel, une femme libre au bagne ». Le Blog Gallica, 20 août 2018. https://gallica.bnf.fr/blog/20082018/louise-michel-une-femme-libre-au-bagne, dernière consultation le 28 mars 2022.