A popular image of the ethnographer consists in imagining them with a notebook and a pencil, scribbling day and night what they have been observing, putting down on paper their first reflections, which will then be analysed and transposed into a journal or a scientific work - in writing or - presented during a communication - through speach.

Often however, ethnographers do not only write: they record on their Dictaphone, film with their camera, take pictures with their camera or phone, and eventually draw. Drawing is a useful tool for remembering a situation, a movement, or an object. It can be done quickly, in the form of a diagram or sketch, which makes it possible to understand or immediately remember a situation observed.1. It is also less intrusive than the camera. The aesthetic quality of the drawing is not the primary aim of these graphic expressions made in the field, although some ethnologists may be recognised for their drawing skills, and some drawings may be used for publication or exhibition.

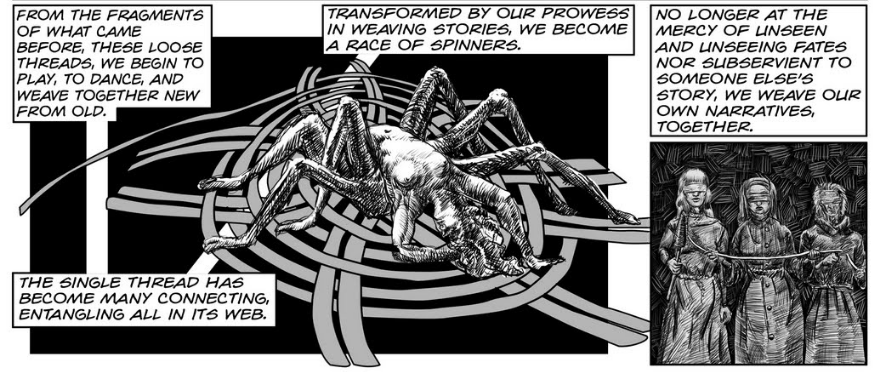

Excerpt from A Treatise on Wild Ecology. Mythopoiesis, by Alessandro Pignocchi, 2020 © Alessandro Pignocchi

Clifford Geertz defines ethnology by "the kind of intellectual effort it embodies [i.e.], an elaborate foray [...] into 'dense description'".2 Drawing seems to be able to respond, in the same way as the written word, but differently, to this exercise. Over the last fifteen years, anthropology has seen an increasing number of publications in which drawing, as a method of investigation and/or a tool for its restitution, is central. Kim Tondeur speaks of the "graphic boom in anthropology", with the term "graphic anthropology" asserting itself among the subfields of the discipline.3

Historically, drawing was a medium widely used by explorers, scientists and the artists who accompanied them, such as Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771) or William Hodges (1744-1797), who embarked on the voyages of Captain James Cook (1728-1779) at the end of the 18th century. In Europe, the engravings resulting from their drawn observations circulated in scholarly circles and the various social spheres, which contributed to making distant worlds known, or rather to creating a mythology about them. The first ethnographic expeditions used drawing, in a realistic style, which corresponded to a logic of rescue and collection of the elements observed. Photography and its "mechanical objectivity"4 then took over. However, visual media - drawing, more than photography - were abandoned by the new schools of anthropology, which supplanted evolutionism and diffusionism. Thus, the written word was imposed by the functionalists and structuralists, drawing rarely being used as a constitutive tool of anthropological knowledge, with a few exceptions.5

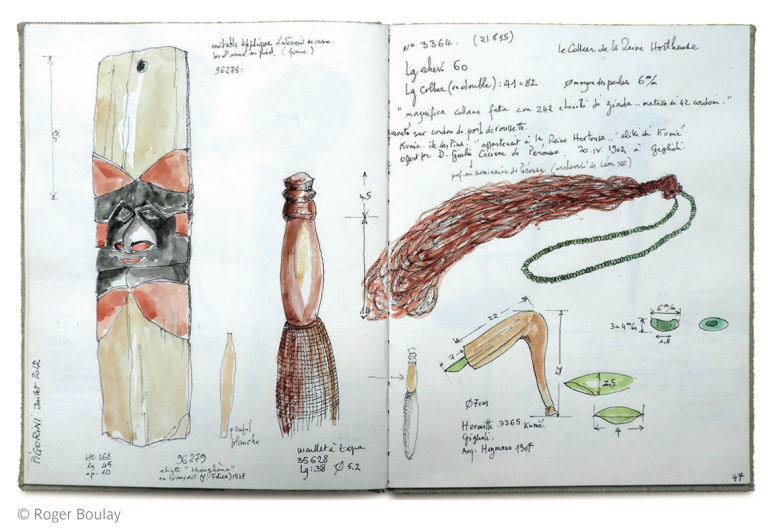

The exhibition Carnets kanak. Voyage en inventaire by Roger Boulay, currently on display at the Musée Hèbre in Rochefort, until June 4th, shows some of the watercolour drawings of Kanak artefacts that Roger Boulay - anthropologist and museologist - has observed in European museums. These drawings are reminiscent of the plates used by botanists or other scientists in the 18th century who, after having taken an overall view of the specimen studied, sketched more specifically certain details and added reading details (size, name, materials, etc.).6 These graphic archives are the result of an investigation carried out in museum storerooms over several years, and ultimately refer to a use of drawing that is part of a long scientific graphic tradition. Similarly, Haidy Geismar shows that the style of the drawings made by Arthur Bernard Deacon (1903-1927), who went to the south of Malekula Island in Vanuatu, refers directly to those made by S. Parkinson and W. Hodges, already mentioned. Hodges, already mentioned. A drawing, like a textual production, is therefore not simply an illustration of a moment, a place or an object, but a particular way of seeing and capturing them, responding to the logics of cultural and social construction in which the ethnographer is caught. They reveal the conditions of production of ethnographic knowledge.7

However, drawing, during or after the ethnographic experience, takes many other forms. While this theme has already been addressed on the blog, this article proposes to explore the issues related to this practice in a more methodological and epistemological way.

Extract from a sketchbook by Roger Boulay © Roger Boulay

In the context of her thesis on "free dances in consciousness"8, Marie Mazzella di Bosco resorted to drawing because during her fieldwork in dance classes, she was not allowed to simply observe, film or photograph. She therefore gave in to the game of dance and these practices of letting go, becoming aware of oneself, one's gestures and one's feelings, in order to reconnect with oneself, with others and with the world. Participatory observation was therefore complete, which led her to question what she was feeling and to find a method to talk about things she was experiencing, (almost) more than she was observing. Her field notebook was therefore not only covered with notes, but also with drawings, colours and reflections related to her experience, in addition to those of others. Her drawings were often taken on the spot, after a lesson, and then taken up again. Some of them translate recurring movements on paper and others, done on a black background, with pastels, the atmosphere of the dance hall. To express the movement, she experimented with techniques in which she represented sequences of gestures or strokes of different types, transcribing the energy felt. The non-realistic character of her drawings also allowed for the anonymisation of her interlocutors. Moreover, their sometimes non-naturalistic aspect favoured the expression of invisible things, such as affects or feelings, as well as energy.9

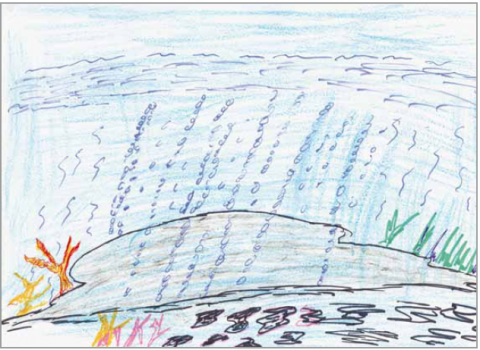

"The volcano is a pebble lying on the bottom of the water", Joel Hendrix, March 2011, Kurumape, Tongoa, Vanuatu © Joel Hendrix/Maëlle Calandra

As part of her research in Vanuatu, Maëlle Calandra used drawing to allow her interlocutors to give her an image of something that is very concrete but difficult to observe. Working on so-called natural disasters, linked to volcanic eruptions for example, she asked her interviewees to draw the underwater volcano off the island of Tongoa, which everyone "seemed to know about, [despite the fact that] its shape and its underwater extent, [are] invisible from the surface, since it is situated at a depth of sixty metres"10.

Since the 19th century, pencils and blank paper have often been passed on to informants. The method first served an evolutionary logic, tinged with psychology, and K. Tondeur hypothesises that drawing may have been a way for ethnographers to "secure a monopoly on words and to confine the Other to the pre-literary culture".11 This method then becomes more pronounced in a participatory approach, as in the case of M. Calandra. Here, the drawing is born of an injunction from the ethnographer, who often guides the theme and, to a greater or lesser extent, the methods used. Michelle Coquet points out that the drawings recovered by Thérèse Rivière during her ethnography among the Ath Adberrahman Kebèche of the Aurès, in Algeria, are interesting because they evoke the "indigenous point of view", but they deal with "pre-established ethnographic categories: production techniques, material culture, ritual practices".12 Similarly, John Mack argues that the drawings made by the Polynesian priest Tupaia, who joined Cook's voyage in 1769, are the result of an apprenticeship in technique, perhaps at the behest of S. Parkinson, who would have guided him - and possibly others - on what to draw.13

However, the graphic injunction, or invitation, can also go beyond the ethnographer's framework or expectations, when the drawers evoke elements that he or she had not anticipated. M. Calandra explains that drawing has made it possible to reveal things that could not be expressed verbally. During her survey on another island, Tanna, she asked her male interviewees what events were damaging the crops. At first they said volcanic eruptions or heavy rains. When she asks them to draw them, some of them reveal other danger factors, such as the presence of menstrual blood in the gardens, which is actually the most feared threat. Drawing, newly introduced in schools in Vanuatu, "is not subject to any explicit prohibition"14, unlike the spoken word, which has a great deal of performative power, and which prevented the men from talking directly about this subject.

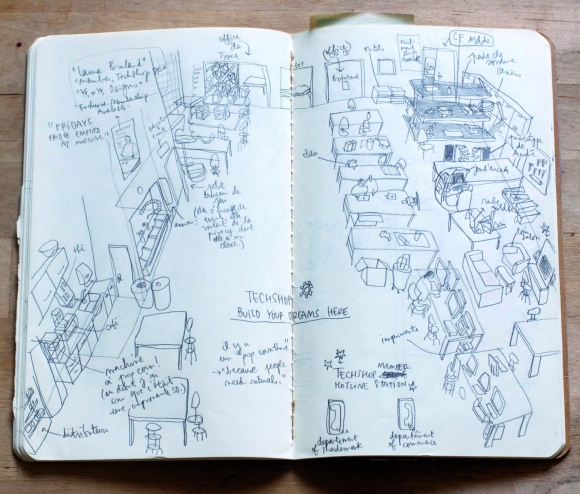

TechShop, general view of the first floor, San Francisco © Camille Bosqué

The drawing thus acts as a trigger when it is difficult to talk about something. It can also arouse curiosity and allow discussions to take place. Camille Bosqué, designer and anthropologist, has drawn a lot during her fieldwork in FabLabs around the world.15 Her notebooks contain quick notes, schematic drawings of the space in which she finds herself, details, portraits, quickly sketched scenes, as well as technical diagrams. Drawing has allowed her to integrate herself into these spaces, functioning around creation and technique. Thus, on the one hand, she could observe and understand her surroundings without interrupting the scenes in progress; on the other hand, her drawings, especially the sketches reproducing the organisation of the spaces, provoked exchanges with the occupants of the premises. For example, some of them enlightened her on objects she had not recognised and others gave her explanations on how the machines worked.

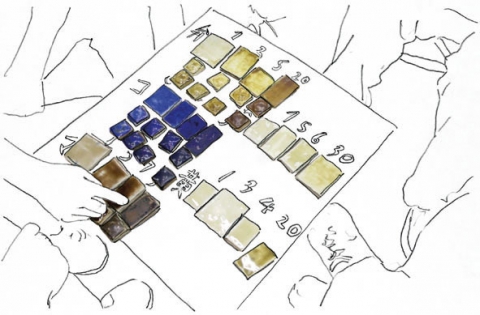

Experimental results © Alice Doublier/Vincent Micoud

I will end this (very) quick tour of the ways in which drawing is used in anthropology, by mentioning an obvious fact: this medium is widely used by anthropologists of techniques, who thus relate, more easily than with words, the implementation of an artefact. A long chain of operations is sometimes tedious to read (and write!) and drawings give a better idea of the steps involved in making an object. The ethnographer can also rely on photographs or films to make them. Unlike photographs, which are sometimes difficult to read, and films, whose speed does not always allow the details of the scenes filmed to be seen clearly, drawings can be enhanced with comments, captions, different colours, etc., which makes them easier to read and understand the techniques studied. In her thesis, Alice Doublier developed drawings from photographs taken in her field, at an art university in Kyōto, where she observed the learning of the ceramic technique.16 Anxious to preserve the anonymity of her interlocutors but eager to render the technical gestures, colours and materials, she has ironed out the outlines of important shapes or people on her photographs, creating black and white drawings. They are uncluttered, this economy created by the mere presence of thin black lines allowing the eye to focus and better grasp which gestures and tools are to be looked at and understood. Accompanied by a friend who is a photographer, she has sometimes added colour to her drawings, in particular to represent the nuances of enamels, the technique of which is difficult to master, and which was experimented with by a few students at the school where she conducted her research.17

Drawing, in the field or when returning from the field, is therefore an experience specific to each researcher and to each ethnographic experience. The techniques used are potentially infinite and are constructed from defined contexts and goals. Contrary to common belief, drawing is rarely an illustration, but reveals and questions the research process. It is therefore necessary, in the same way as a text, to question its mode of existence.

The "graphic culture of our Western society"18 leads to the reinvestment of this medium and influences the production of images and their narration. However, the drawing is not easy to present, outside of exhibitions. Beyond its realization, its edition can be difficult to hope to obtain legible and good quality reproductions. The academic world is perhaps still a little reluctant to let itself be invaded by lines drawing something other than letters. Nevertheless, a few experiments are affirming the place of drawing in this sphere. In 2014, the American Nick Sousanis defended the first thesis done in comics, Unflattening, published in 2016.19

Extract from Unflattening © Nick Sousanis

Drawing is also a way of taking research out of the academic field. The world of ethnology is therefore increasingly joining forces with artists to create projects that are accessible to all. As the ninth art form aimed at the general public, comics - and to a lesser extent graphic novels - are widely used. Collaborative projects between cartoonists and anthropologists are illustrated and published, for example in the Canadian series EthoGRAPHIC by the University of Toronto Press.20 In addition to being a method that allows the ethnographers' interlocutors to co-create a representation of themselves, drawing is also a more accessible tool for the restitution of research. Although K. Tondeur points out that French-speaking anthropology still has few examples of ethnographers using drawing, the above examples show that drawing experiences do exist, but perhaps they are still not made visible... get your pencils ready!

Garance Nyssen

Pour d’autres ressources sur le dessin et l’anthropologie, vous pouvez consulter le billet de Fabien Roussel et d’Emilie Guitard publié sur le carnet Hypothèse de la revue Terrain : https://blogterrain.hypotheses.org/17017.

Explorez aussi l’exposition numérique Illustrating Anthropology réalisée par Laura Haapio-Kirk et Jennifer Cearns, soutenue par le Royal Anthropological Institut : https://illustratinganthropology.com.

Cover picture: Amim Khan the bow reader, Tom Crowley, 2018 © Tom Crowley

1 Geismar Haidy, « Drawing it out », Visual Anthropology Review, vol.30, 2014 (2) : 97-113 : 99.

2 Geertz Clifford, « La description dense. Vers une théorie interprétative de la culture », Enquête, 1998 (6) : 73-105 : 75.

3 Tondeur Kim, « Le Boom Graphique en Anthropologie », Omertaa, 2018 : 704-720. Kim Tondeur points out that the paternity of the expression 'graphic anthropology' certainly belongs to the English anthropologist Tim Ingold, in his book Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture (2013).

4 Tondeur Kim, 2018, op.cit. : 707.

5 Drawing is still widely used in the field of cognitive anthropology. Margaret Mead (1901-1978) and Gregory Bateson (1904-1980) use it in particular to understand the cognitive development of children and young adults. A whole article could be dedicated to this use of drawing!

6 This exhibition was originally intended to take place at the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in 2020, which was not possible due to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, the catalogue was published: [Exhibition. musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris], Carnets kanak : voyage en inventaire de Roger Boulay, Paris : musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, 2020.

7 Geismar Haidy, 2014, op.cit. : 99.

8 The expression "free dances in consciousness", given by M. M. di Bosco, refers in fact to three types of dances: Movement medicine, 5 rhythms and open floor. These practices are collective, mixed, rather western. The dancers are guided by a teacher-facilitator who builds playlists rather than teaches movements, Ethnographie d'un travail spirituel contemporain : Danses Libres en Conscience en Île-de-France (Danse des 5 Rythmes, Movement Medicine, Open Floor), thesis in anthropology, Université Paris Nanterre, 2020.

9 Some of her drawings can be seen in her thesis which is available online. These information were collected during a master course in anthropology given by M. M. Di Bosco at the University of Paris Nanterre (2021). A cartoon rendition of a field moment can also be seen in her article ‘Danser la relation’. Interactions en mouvement dans les danses libres en conscience, Ateliers d’anthropologie, 50, 2021 [DOI : 10.4000/ateliers.14618].

10 Calandra Maëlle, « Faire dessiner le terrain », Techniques & Culture, 60, 2013 : 182-201 : 185.

11 Tondeur Kim, 2018, op.cit. : 709.

12 Coquet Michelle, « L’« album de dessins indigènes », Thérèse Rivière chez les Ath Abderrahman Kebèche de l’Aurès (Algérie) », Gradhiva, 2009 (9) : 188-203 : 202.

13 Mack John, « Drawing degree zero: the indigenous encounter with pencil and paper », World Art, 2 (1), 2012 : 79-103 : 83. In this article, J. Mack argues that the first introductions of paper and pencil to non-drawing communities led to conceptual rather than technical innovation. This innovation lies primarily in imitation (98-99).

14 Calandra Maëlle, 2013, op.cit. : 195.

15 Bosqué Camille, « Enquête au coeur des FabLab. Le dessin comme outil d’observation », Techniques & Culture, n°64, 2015 : 168-185.

16 Doublier Alice, La texture du monde. Apprendre la céramique dans une université d’art de Kyōto, PhD in anthropology, Université Paris Nanterre, 2017.

17 Doublier Alice, « Essai d’ethnographie dessinée. Les mystères des cristaux d’oxyde de zinc ou comment apprendre l’art délicat des émaux céramiques », Techniques & Culture, 68, 2017 : 48-65.

18 Tondeur Kim, 2018, op.cit. : 709.

19 This is a thesis in educational sciences, dealing with the potentialities of visual perception and thinking.

20 EthnoGRAPHIC, University of Toronto Press [URL : https://utorontopress.com/search-results/?series=ethnographic], accessed on May 19th 2022.

Bibliography:

- BOSQUÉ Camille, « Enquête au coeur des FabLab. Le dessin comme outil d’observation », Techniques & Culture, n°64, 2015 : 168-185.

- CALANDRA Maëlle, « Faire dessiner le terrain », Techniques & Culture, 60, 2013 : 182-201.

- COQUET Michelle, « L’« album de dessins indigènes », Thérèse Rivière chez les Ath Abderrahman Kebèche de l’Aurès (Algérie) », Gradhiva, 2009 (9) : 188-203.

- DI BOSCO Marie Mazzella, « ‘Danser la relation’. Interactions en mouvement dans les danses libres en conscience », Ateliers d’anthropologie, 50, 2021 [DOI : 10.4000/ateliers.14618].

- DI BOSCO Marie Mazzella, Ethnographie d’un travail spirituel contemporain : Danses Libres en Conscience en Île-de-France (Danse des 5 Rythmes, Movement Medicine, Open Floor), thèse en anthropologie, Université Paris Nanterre, 2020.

- EthnoGRAPHIC, University of Toronto Press [URL : https://utorontopress.com/search-results/?series=ethnographic], accessed on May 19th 2022.

- DOUBLIER Alice, « Essai d’ethnographie dessinée. Les mystères des cristaux d’oxyde de zinc ou comment apprendre l’art délicat des émaux céramiques », Techniques & Culture, 68, 2017 : 48-65.

- DOUBLIER Alice, La texture du monde. Apprendre la céramique dans une université d’art de Kyōto, PhD in anthropology, Université Paris Nanterre, 2017.

- [Exposition. musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris], Carnets kanak : voyage en inventaire de Roger Boulay, Paris : musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, 2020.

- Illustrating Anthropology [URL : https://illustratinganthropology.com], dernière consultation le 19 mai 2022.

- MACK John, « Drawing degree zero: the indigenous encounter with pencil and paper », World Art, 2 (1), 2012 : 79-103.

- ROUSSEL Fabien et GUITARD Emilie, 13 juillet 2021, « L’usage du dessin dans l’enquête de terrain en sciences sociales. Etat des lieux et perspectives depuis la géographie et l’anthropologie (première partie), Carnets de Terrain [URL : https://blogterrain.hypotheses.org/17017], dernière consultation le 19 mai 2022.

- TONDEUR Kim, « Le Boom Graphique en Anthropologie », Omertaa, 2018 : 704-720.

- INGOLD Tim, Faire : Anthropologie, Archéologie, Art et Architecture, Bellevaux : Editions du Dehors, 2017.

1 Comment so far