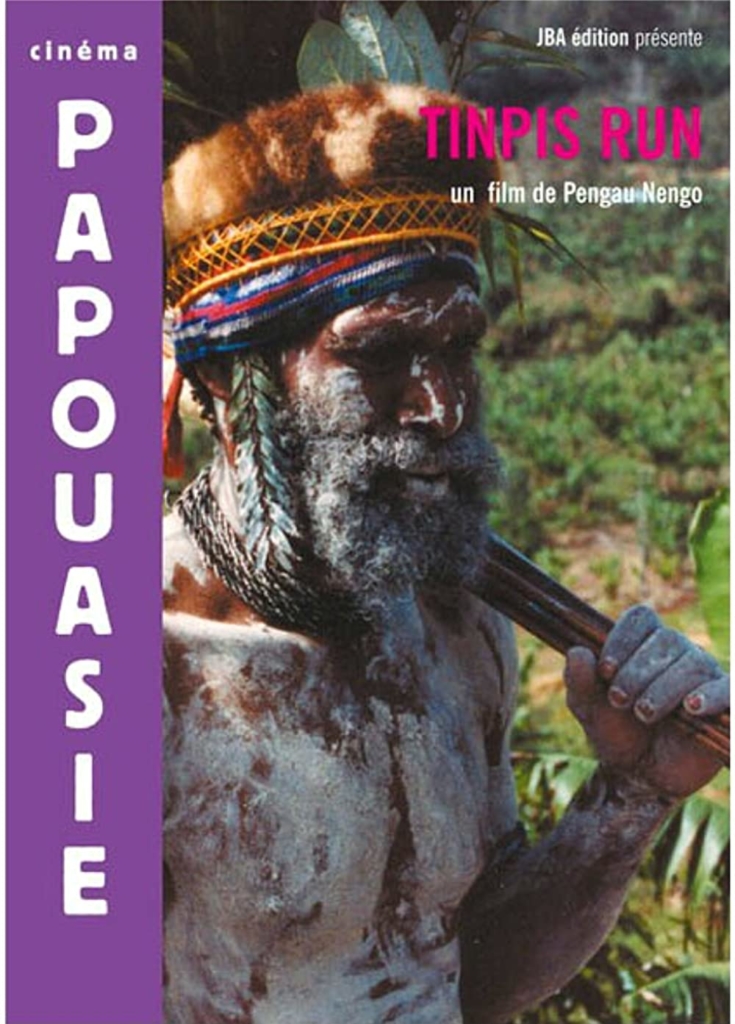

Tinpis Run is often referred to as Papua New Guinea's first fiction film. Although the first movies made by Indigenous people, particularly in the capital Port Moresby, date back to the 1970s, Tinpis Run is the cult film of Papua New Guinea cinema. This road movie in Tok Pisin with English and French subtitles, directed in 1991 by Pengau Nengo, was a success internationally. The film was nominated at the Locarno International Film Festival and the Valladolid International Film Festival. - It received a special mention at the Rotterdam International Film Festival in 1991 as well as the Best Actor Award at the Balafon Festival in 1996. So, this week, let's go on the road of this movie full of humour and poetry!

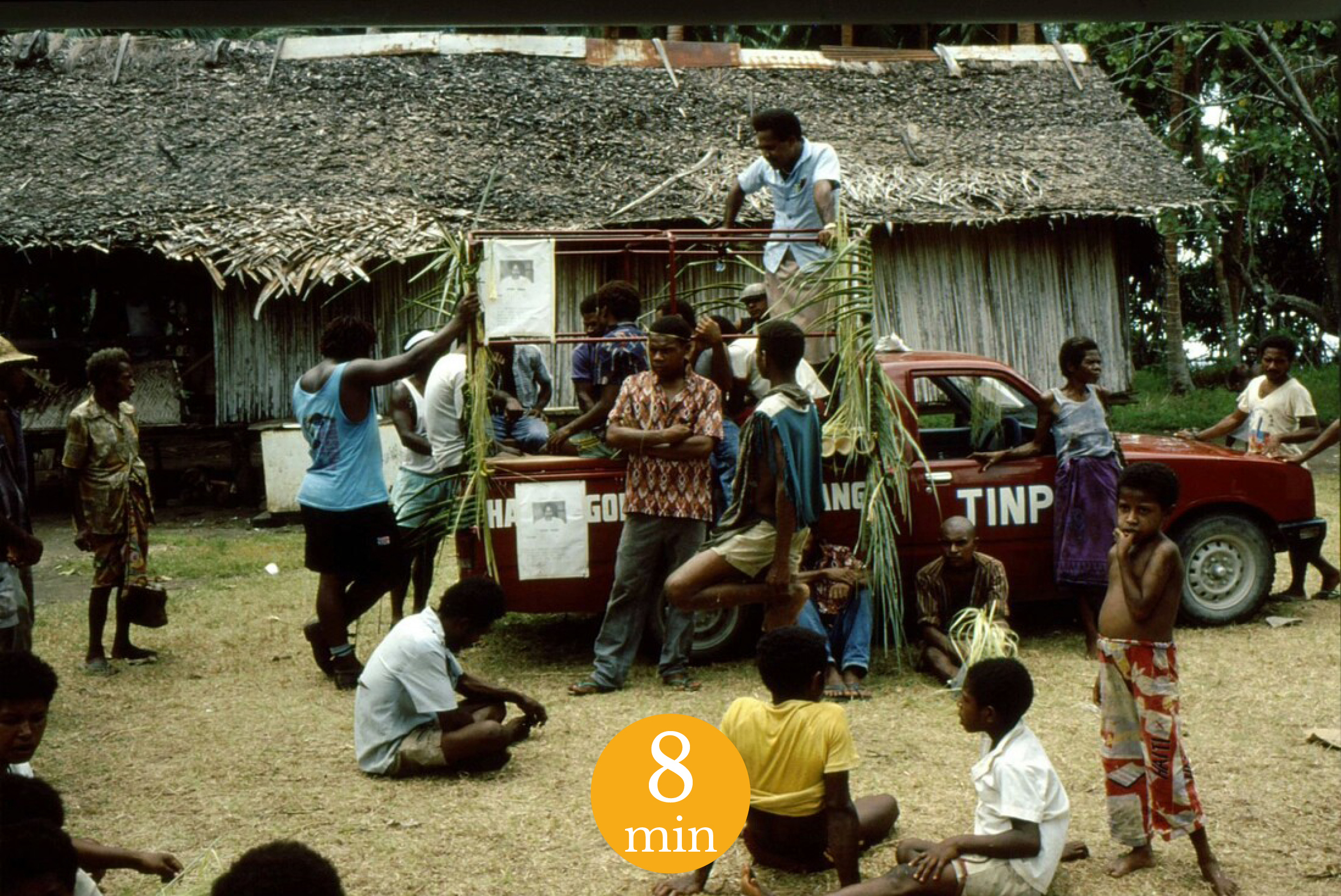

The film follows the adventures of Papa, a chief of a Highland tribe (played by Leo Konga). The film begins with Papa who gets into a drunken car accident on his way home from a long evening with a friend. In a bus behind them, his daughter Joanna (played by Rhoda Selan) and Naaki, a young man from the Sepik (played by Oscar Wann) who was hitting on her, come to help Papa. He receives an allowance of 7,000 kina and decides to use it to buy a taxi. Papa buys the car from Pete, an Australian (played by Stan Walker). The scenes between the Australian Pete and Papa are particularly funny. Pete's colonial attitude is ridiculed: Papa calls him Mastathe Tok Pisin term for white people, derived from the English MasterPete thinks he is fooling Papa, but it is he who is fooled by Naaki and Papa who pay him in fake coins. With this new car, Papa and Naaki start their business, a taxi from Mount Hagen to Madang via Goroka and Lae. The new taxi, named Tinpis, is inaugurated in the village with a big party. The film follows the adventures of the two men from town to town. Through them, the landscape and history of Papua New Guinea in the 1980s are revealed. On their way, they meet Peter Subek (played by Gerard Gabud) and lose everything to him in a gambling match. Peter is also an unscrupulous politician who offers them a deal: money and fame if they follow him to the island of Langur and work with their taxi so that he, Peter, can win the provincial elections. Papa, Naaki and Tinpis end up going around the island to promote Peter Subek's speech. The scenes are particularly comical: the speech is always the same, the same grand plan for the development of the island (in which the taxi is the symbol), and fewer and fewer people attend the speech.

Papa and Naaki eventually make it back to Madang and decide to return to the village because a fight with a neighbouring village is raging. Tinpis is stolen by some bandits on the way back and finally recovered before Papa returns to the village. His daughter Joanna convinces him to surrender.

Car accident scene

While the comedy is still funny today, the film is a poignant account of an important moment in Papua New Guinea's history: the post-independence 1980s. Tinpis Run, like most films produced in the country since the 1970s, explores the highly visible social changes that occur rapidly from one generation to the next.1 The duo Papa and Naaki is a perfect example of the clash between two generations: one older, raised in a "traditional" village context, and the other younger, educated in an urban, "modern" context. Naaki and Joanna illustrate the difficulties of the new generations torn between new career and travel opportunities and their obligations to their parents and customary practices. The differences between Papa and Naaki are apparent from the moment they meet. Papa first gives Naaki his daughter's hand in marriage as a gesture of gratitude, but she refuses. Naaki, on the other hand, represents the younger generation described as men who particularly like to court different young women, which exasperates Papa. Both positions are ridiculed to show their limits.

The final scenes deal with the conflict between the two villages. Papa is injured and Joanna, his daughter, manages to reason with him to stop the conflict. Finally, peace is established in the presence of the local police and magistrates - signs of order and justice in a national context. All meet in the middle of a road to compensate for the losses of both villages. The scene is particularly comical thanks to the many interruptions created by passing trucks. This scene is a way to show the hope of the new generations for a future without conflict.

Poster of the film Tinpis Run by JBA production © JBA production

The film depicts the situation of the country after independence and the still visible impact of Australian colonisation. The aforementioned car salesman, Pete, is a good example. Another recurring character in the drama is Papa, who meets two French-speaking missionaries on several occasions, first breaking down on the side of the road and then hitchhiking. The character of Pete allows us to see the persistence of bars and clubs in the cities after the independence in 1975. These places of sociability created and frequented by Australian settlers and administrators still exist in the 1980s and 1990s. Deborah Gewertz and Frederic Errington discuss the history of these clubs and their gradual use by Indigenous people to demonstrate their new status.3 The emergence of a middle class is one of the most important social movements in the country at that time. The politician Peter Subek is a very good example. Some men gained access to new positions and circles of sociability, creating a local elite.4

Again with the figure of Peter Subek, the film refers to the almost omnipresence of gambling in the country. Papa loses everything in card games to the politician. The first accounts of these games - studied by the anthropologist Anthony Pickles - date back to the beginning of the 20th century, but it was after the Second World War that they took off in a big way. Circles of sociability were created around the game and personal and social identities developed.5 Tinpis Run captures the social dimension of the games, which involve more than just the players. Indeed, spectators, both men and women, come to attend and the games last all night until the early hours of the morning.

Tinpis Run, although a fictional film, takes on a whole new dimension when one considers the history of film and the camera in Papua New Guinea and more specifically in the Highlands. The film can then be understood as a kind of response to documentary films made about the country by non-indigenous people. This is all the more important when one remembers that the Highlands were among the last territories to be subjected to Australian colonial rule and that the camera wasan integral part of this colonial history of the Highlands. The Leahy brothers filmed their 'discoveries' in the 1930s and marked the camera's entry into the region. This footage was used in the film First Contact directed in 1982 by Bob Connolly and Robin Anderson.6 In contrast of First Contact and sixty years after the Leahy brothers, it is the Indigenous people of Papua New Guinea who hold the camera and tell their story, their own lives with their own points of view!7 The choice to show and explore social change is the focus of earlyIndigenous productions since the 1970s. Through these themes, these films serve as a playground for the exploration of new local and national identities.8 Tinpis Run is particularly committed to the promotion of a new national identity, which is reflected in the casting and crew of the film. The director, Pengau Nengo, belongs to that first urban and educated generation that identifies itself as Papua New Guinean and not as coming from a particular place or people. He was born in Morobe Province to a Gulf mother, his wife is from Central Province and they live in Goroka in the Eastern Highlands. Nengo briefly studied dance and theatre at the Dance Theatre in Harlem, USA.9 The choice of actors is also particularly interesting. Papa is played by a highland chief from the Mokei clan.10 Naaki is played by a Sepik man. The choice of actress for Joanna is particularly enlightening: the actress Rhoda Selan is not from the Highlands like the character she plays, but from Manus. This choice is indicative of a desire to stage a national identity, a pan-Papua New Guinea image beyond regional specificities.11 The very genre of the road movie allows the action to be set in a wider territory than a single province, making the film inherently pan-Papua New Guinean.

Still from the movie Tinpis Run. Papa (on the left), his taxi Tinpis and Naaki (on the right) © NENGO, 1991.

The film is unique, even today, as it has international funding and support. Tinpis Run was born from the collaboration of the national cinema school, Skul Bilong Wokim Piksa and the Ateliers Varan. The Skul was founded in 1979 in Goroka by the Australian architect, Paul Frame. The aim is to train young people to make films and stories relevant and appropriate to the different communities in the country. With the idea of developing this structure, Paul Frame established an exchange programme with the ateliers Varan in Paris. French film professionals Jacques Bidou and Severin Blanchet travelled to Goroka on several occasions to teach.12 in 1985, three students from the Skul are invited to participate in a workshop in Paris. Pengau Nengo, Martin Maden and Bike Johnstone are there. During the workshop they made a short documentary film about Anthony Mastalski (which I highly recommend you to watch), an 85 year old Polish immigrant in the Paris area.13 The team edited the film in the workshops of the Musée de l'Homme and it was a success! It won the prize for the best ethnographic film on France in 1986.14 It is at that time that they start thinking about the Tinpis Run project. The material and financial support provided by the Varan workshops corresponds in every respect to the objective that the workshops set themselves when they were founded in 1981, at the initiative ofu the director and anthropologist Jean Rouch. The ateliers were created to train filmmakers from the Global South. For the production of Tinpis Run, the ateliers Varan are supported by JBA production, a group with the same desire to support projects by new talent from the Global South. In addition to the ateliers, Channel 4, Le Sept Tv France and RTBF Belgium have provided grants for Tinpis Run with a total budget of 500 000 Australian dollars, quite exceptional for a film made in Papua New Guinea. The international context in which the film was produced had an impact on its outcome. Since it was funded by foreign institutions, it had to be comprehensible not only in Papua New Guinea but also in England, France and Belgium. An anecdote from Rod Stoneman is particularly enlightening in this regard. He visited the ateliers during the editing process in Paris and, when the first version was showed, he recounted how a scene involving an argument between two men, and then a fight, seemed very chaotic and difficult to follow. Stoneman had not understood that the two men had moved to a different village to fight: the houses in the background were not the same in the different scenes, the first being on stilts while the second was on the ground. Butwhat seemed obvious to the filmmakers was not at all obvious to the British eye. Rod Stoneman had a car scene added to make the film more intelligible to a Western audience.15

Other international influences can be seen in the film. This is particularly the case of Papa's accident scene. It uses the codes of stunts and accidents of American productions, giving a rather kitschy and comical final result. The genre and the scenario are also influenced by the director's stay in Paris and his encounter with French cinema. Indeed, Pengau Nengo was inspired by what was then called "direct cinema" or "cinéma vérité". In Tinpis Run, one can see clear references to French movies like Jour de fête by Jacques Tati and François, the postman, caricatured and comical role, or Cocorico by Jean Rouch, the history of Lam, his trainee Talon and their 2CV, Patience. 16

The impact of Tinpis Run in Papua New Guinea was initially much less than that abroad. Although the film was shown many times in France and Belgium, it was not shown until years later on the national television station, EMTV (Papua New Guinea's television station established in 1987). Tinpis Run today it represents a unique testimony of a moment in the history of Papua New Guinean cinema.

Enzo Hamel

Cover picture Still from the movie showing Peter Subek on Tinpis on the island of Langur © NENGO, 1991.

1 ASBURY EBY, M., 2017. The Story of Aliko and Ambai: Cinema and Social Change in Papua New Guinea. Thèse sous la direction de Heather Horst et Verena Thomas, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, p. 28.

2 ASBURY EBY, 2017, p. 34.

3 Voir GEWERTZ, D. et F. ERRINGTON, 1997. The Wewak Rotary Club: the middle class in Melanesia. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 333-353.

4 Voir GEWERTZ, D. et F. ERRINGTON, 2006. Emerging Class in Papua New Guinea: The Telling of Difference. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

5 Voir PICKLES, A., 2019. Money Games: Gambling in a Papua New Guinea Town. New York, Berghahn.

6 Voir l’article de CASOAR sur la trilogie de Bob Connolly et Robin Anderson, https://casoar.org/2018/04/11/the-highlands-trilogy-un-monument-danthropologie-visuelle/

7 Pour plus de détails sur l’histoire de la caméra et du cinéma dans les Hautes-Terres, voir ASBURY EBY, 2017, pp. 6-7

8 Voir SULLIVAN, N., 1993. “Film and Television Production in Papua New Guinea: How Media Become the Message.” Public Culture, Vol. 5, pp. 533-555 et SULLIVAN, N., 2003. “How Media Became the Message in Papua New Guinea: A Coda.” Spectator, Vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 27-32.

9 SULLIVAN, 1993, p. 549 et note 17.

10 SULLIVAN, 1993, p. 547.

11 SULLIVAN, 1993, p. 547.

12 ASBURY EBY, 2017, p. 33.

13 Pour voir le documentaire Stolat réalisé par Pengau Nengo, c’est ici https://vimeo.com/142111424

14 MADEN, M., 2019. “L’émergence du film d’auteur en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Une trajectoire personnelle.” Journal de la Société des Océanistes, No. 148, p. 32.

15 STONEMAN, R., 2013. “Global Interchange: The Same, but Different.” In: Hjort, M. (ed.) The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. Global Cinema, p. 74.

16 MADEN, 2019, p. 30.

Bibliography:

- ASBURY EBY, M., 2017. The Story of Aliko and Ambai: Cinema and Social Change in Papua New Guinea. Thèse sous la direction de Heather Horst et Verena Thomas, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.

- BIDOU, J., E. CUSNIR et E. SAINT-DIZIER, 1998. “Produire des films avec les pays du Sud. Questions à Jacques Bidou.” Cinémas d’Amérique Latine, no. 6, pp. 144-147.

- BONNEMERE, P., 2019. « Chris Owen en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée : entre idéal collectif et vocation personnelle ». Journal de la Société des Océanistes, No. 148, pp. 37-51.

- GEWERTZ, D. et F. ERRINGTON, 1997. « The Wewak Rotary Club: the middle class in Melanesia ». The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 333-353.

- GEWERTZ, D. et F. ERRINGTON, 2006. Emerging Class in Papua New Guinea: The Telling of Difference. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- MADEN, M., 2019. “L’émergence du film d’auteur en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Une trajectoire personnelle.” Journal de la Société des Océanistes, No. 148, pp. 23-36.

- PICKLES, A., 2019. Money Games: Gambling in a Papua New Guinea Town. New York, Berghahn.

- STONEMAN, R., 2013. “Global Interchange: The Same, but Different.” In: Hjort, M. (ed.) The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. Global Cinema. New York, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 59-78.

- SULLIVAN, N., 1993. “Film and Television Production in Papua New Guinea: How Media Become the Message.” Public Culture, Vol. 5, pp. 533-555.

- SULLIVAN, N., 2003. “How Media Became the Message in Papua New Guinea: A Coda.” Spectator, Vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 27-32.

1 Comment so far