Trigger warning: this article mentions sexual violence against minors.

It is one of the most famous mutinies in history. The events were written about by Jules Verne and brought to the screen by Marlon Brando.1 Through literature and film, the Bounty Mutineers have personified an ideal of freedom. But what do we really know about these mutineers and the legacy they left on Pitcairn, the small Pacific island on which they settled? Immediate boarding for a space-time journey: towards Tahiti in the last third of the 18th century.

He who sows the wind...

Portsmouth, December 1787: the Bounty, a transport ship of the British Royal Navy, set sail for Tahiti to collect breadfruit plants and transport them to Jamaica where they would be used to feed the slaves on the plantations at a lower cost. William Bligh, an experienced navigator (who had travelled alongside James Cook) led the expedition with some forty sailors under his command. Very quickly, the crossing was difficult. The crew suffered from capricious weather and the wrath of a captain judged to be tyrannical. It was only after two weeks, during an unscheduled stopover in the Azores, that the first major tension between Bligh and his crew erupted against the backdrop of missing cheeses. The captain was stern and uncompromising in the face of the sailors' protests. He also appointed one of them, Fletcher Christian, to be his eyes and ears for the rest of the voyage. Four months after its departure, in April 1788, the Bounty reached Cape Horn but headwinds forced it to turn back towards the Cape of Good Hope. There, a new route plan was drawn up. Finally, in October 1788 - ten months after its departure and four months after the planned date - the Bounty anchored in Tahiti.

When he arrived, Bligh took a decision that would prove fatal: rather than occupy his crew, he gave them free rein. For five months, the sailors happily blended in with the population. In March 1789, when it was time to weigh anchor, there were strong protests and three sailors even tried to desert. Despite this, the Bounty managed to leave. But something was afoot on board: on 28 April, a mutiny orchestrated by Christian and four other sailors broke out. Bligh and about fifteen of his followers were abandoned at sea on a longboat2 while the Bounty sailed back to Tahiti. Although the arrival on the island marked the end of the voyage for some of the mutineers, nine of them, including Christian, continued their journey, accompanied by six Tahitians and twelve Tahitian women. After several failed attempts to dock, the small group finally found refuge on Pitcairn, an uninhabited islet of about 5km2. The location is strategic: situated more than 2000 km from Mangareva (the nearest inhabited island), it is one of the most isolated territories in the world. Moreover, the islet is poorly positioned on English navigational charts, making it extremely difficult to find. For the mutineers, this was the promised land: they landed in a rowboat and then quickly set fire to the Bounty, with no turning back.3

Map of French Polynesia showing Pitcairn islands. © CASOAR

The story could have ended there. The film Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), directed by Lewis Mileston, ended with the settling on Pitcairn and played a major role in popularising the story of the mutiny.4 However, the rest of the story cannot be ignored.

Radio silence

For twenty years, the Pitcairn mutineers were nowhere to be found and it was not until 1809 that an American flag spotted a man waving from one of the bays.5 He was John Adams, the last survivor of the island's mutineers.6 He told the sailors his story. Far from the stereotypical image of free men looking for a new world to rebuild, the mutineers established an unequal and violent micro-society on the island, reflecting the power relations of the time. On their arrival, they divided up the land and the women, reducing the Tahitians to slavery. It was in this context that a conflict broke out between mutineers and Tahitians over the possession of women, making the island the scene of a bloody massacre.7 Four mutineers were killed. The last survivors died of various ailments in the following years.8

Would this be the end of the story? No because the mutineers had children. In the first third of the 19th century, as whaling became a lucrative business, the life of the Pitcairnese was marked by regular raids by American whalers in search of supplies.9 To protect themselves, the islanders asked for British support and in 1838 Pitcairn was placed under British protection. However, there were few links between the island and the Crown. In 1853, Arthur Quintal, a descendant of a mutineer, approached Queen Victoria about the possibility of considering the island as a colony; a favourable reply was received the following year. About forty years later, England intervened at the request of the inhabitants in a murder trial. This was the only clear evidence of Pitcairn's legal inclusion in the Empire.10 No further contact took place until the 1970s, when the first official British visit to the area was made during the French nuclear tests.11

Besides this link to the Crown, one can note the installation on the island of Paul Warren, an American beachcomber112, in the 1820s13 as well as the presence of missionaries of the 7th Adventist Church.14 Apart from these few external contributions, Pitcairn's autarky is perfect. The demography remained low, with a maximum of 236 inhabitants in 1930, but the population remained stable.15 Life was organised around a few large families among whom a mayor was elected and the entire community ensured that order was maintained. The inhabitants live by gathering, hunting, fishing and breeding. In the twentieth century, apart from a trade in small handicrafts for passing ships and the sale of rare stamps coveted by stamp collectors, Pitcairn did not trade with the outside world. Life on the island was monotonous, apart from perhaps a few events such as the bank holidays on 29 January commemorating the burning of the Bounty, the founding act of Pitcairn society.17

For over two hundred years, Pitcairn was almost forgotten by everyone, but in 1996, an event brought the small island into the spotlight.

Pitcairn residents in 1916. © Public domain

The Case

In the spring of 1996, an Australian yachtsman went to a police station in New Zealand where he filed a complaint about the rape of his 12-year-old daughter during a stopover on Pitcairn Island. In London, the Foreign Office took the case seriously: a commissioner, a superintendent of police from Scotland Yard18 and a lawyer19 were sent to the scene. The alleged perpetrator was a 55-year-old father.20 He confessed to the crime but claimed the girl's consent. The case was dismissed.21 However, the British judiciary was very concerned about what they saw on site. Sex by adult men with underage girls, sometimes from their close family circle, appears to be common. Some girls as young as 15 years old already have several children, sometimes by different fathers.22 As the age of consent is 16 under British law, an investigation was launched.23 This led to the opening of a trial in 2004. Of the 50 or so islanders, six were convicted of paedophile offences, almost a third of the men on Pitcairn.sup>24

While it is clear that young girls are having sex from puberty, the investigation remains difficult. The justice system goes back to the 1960s and questions women about events that occurred when they were under 16. It even offers financial rewards and the possibility of going abroad to those who agree to talk. However, none of the inhabitants testify. The only complaints received were from women who had emigrated abroad (to Australia or New Zealand).25 In the dock, no one denied the facts, but all disputed the British intervention and asserted the sovereignty of Pitcairn. In their defense, they invoked their own customs, dating back to the first inhabitants of the island.26 Moreover, if the island was officially an English colony, a legal problem arose. Indeed, the facts reproached were offences under the Sexual Offences Act of 1956, of which the inhabitants of Pitcairn had not been notified. The question then arose: could men be convicted for breaking a law of which they were, in principle, unaware?27

What came to be known as the Case with a capital 'C' was much discussed, both in terms of the legitimacy of Britain's intervention and the reasons for it. One of the main French commentators on the events was Louis Assier-Andrieu, an anthropologist and historian, professor at the Sciences-Po Paris law school. He seized on the affair to question the legitimacy of human rights to interfere in a culture that did not comply with its principles. Thus, he questions the notion of "evil in itself", a legally vague tool that "offers a powerful lever to annihilate its targets". He describes it as "absolute universalism, the face of a single law or a jurisdiction without appeal". For him, the behaviour of the men of Pitcairn is part of a culture whose uniqueness must be taken into account.28 On the island, sexual relations with young girls who have just reached puberty were accepted and, until then, outsiders including American whalers calling on the island, had never condemned these practices (sailors on the contrary took advantage of these young girls who were able to give themselves in exchange for a little food).29

But what culture are we talking about? How did it come to pass on Pitcairn Island that adult men have sex with girls as young as ten?

The sailor and the vahine

For Assier-Andrieu, the Pitcairnese created their own culture, borrowing from the traditions of the English Navy, Tahiti and the Adventist Church. He seems to agree with the defendants about their claim to belong to a Tahitian culture that tolerates a great deal of sexual freedom. However, for Olivier Goujon, journalist, photojournalist and author of Pitcairn, les révoltés du Bounty vont disparaître (2021), the argument is difficult to understand. Indeed, the small society is based on the enslavement of Tahitians by the English mutineers. So how can it claim to be Tahitian, while having been founded in the image of its dominant members?30

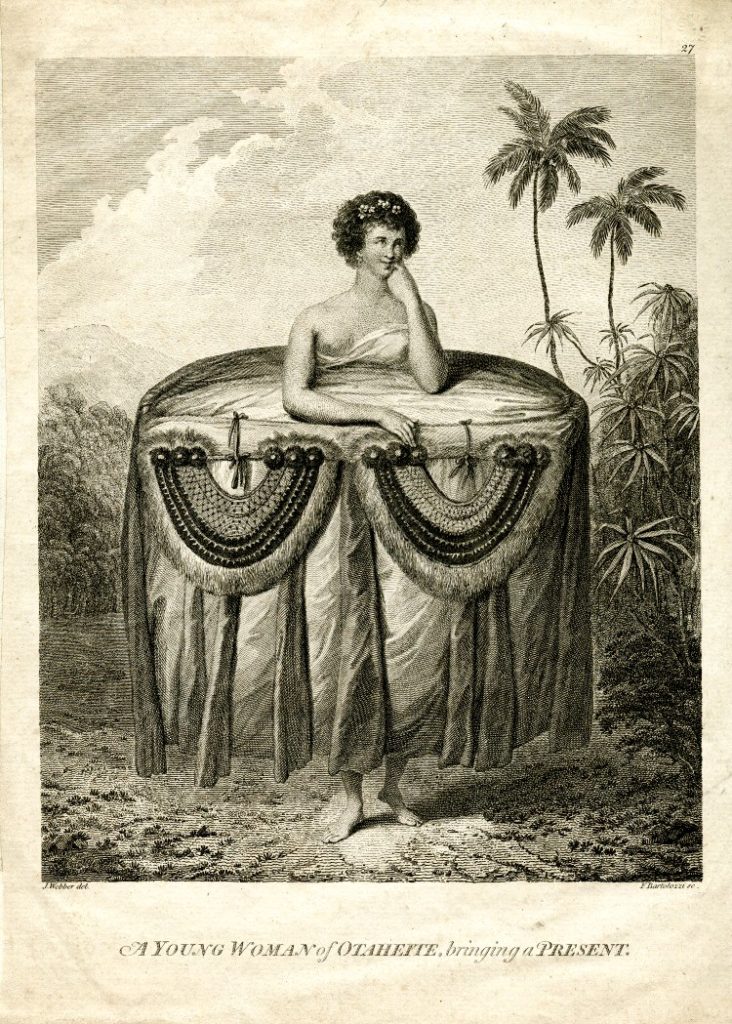

To understand this claim of the Pitcairnese, we have to go back to 1771. That year, the French navigator Louis-Antoine de Bougainville published his Voyage autour du monde. He was the first to describe what would come to be known as Tahitian hospitality. He mentions the warm and welcoming inhabitants but above all the young girls offered to the sailors who were encouraged to have sexual relations with them. For him, the Tahitians "breathe only the pleasure of the senses". Other members of the expedition report a similar experience, describing the islanders as "a free people, devoid of any sense of shame or jealousy, carefree and concerned only with their pleasures". In European scholarly circles, the publication quickly became the talk of the town.31 Two years later, it was the turn of the English explorer James Cook to publish an account of his voyage to Tahiti. His descriptions were similar to those of Bougainville.32 In addition, the painters on board the expedition brought back the first images of vahine (Tahitian for woman). Objects of desire, they quickly became a source of inspiration for European artists, who willingly depicted them in so-called "lascivious" dance postures.33 Thus, when the Bounty set sail in December 1787, Tahiti was for the sailors a fantasy land, populated by nymphs whose beauty was equalled only by their freedom.

A young woman of Otaheite, bringing a present, 1780/85, gravure d’après John Webber. Source : https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=3186857&partId=1

But did Tahiti really embody the ideal of freedom that the Europeans thought it did? And were the Tahitians really this unashamed people, praised for the purity of their intentions and the ardour of their desires?

Dans les récits de l’époque, certains motifs récurrents questionnent. Tout d’abord, il y est rapporté que les marins ont des rapports sexuels uniquement avec des jeunes filles. Les femmes mariées ne leur sont jamais offertes. Ensuite, l’acte sexuel est très souvent pratiqué en public, sous les encouragements des villageois. Les marins en concluent que la coutume est à la liberté sexuelle et que seule la jalousie d’un mari peut y mettre fin.34 Mais si Tahiti incarne un idéal de liberté, comment expliquer le mécontentement des tahitiens face à la réticence de certains marins ?35 Et comment interpréter les larmes de certaines vahiné que Bougainville décrit comme semblant “ne pas vouloir ce qu’elles désirent le plus” ? Comment comprendre qu’elles ne se présentent jamais seules mais soient toujours accompagnées d’un chef ou d’une personne âgée ?36 Si les marins peinent à expliquer ce qu’ils découvrent à Tahiti, la référence constante aux grands récits européens (mythologie gréco-romaine, Bible) ainsi que l’usage récurrent de mots comme “temple” ou encore “culte” dans leurs récits de voyage témoigne d’une intuition que ces événements sexuels relèvent d’une pratique ritualisée, fortement symbolique.37 L’anthropologue américain Marshall Sahlins dans son Supplément au voyage de Cook (1989) offre une piste intéressante d’interprétation de ces pratiques, aujourd’hui largement admise. Pour lui, les tahitiens ne voyaient pas les européens comme des humains mais comme des divinités ou des esprits.38 Le français Serge Tcherkezoff va dans le même sens en parlant “d’envoyés du monde divin”.39 Cette confusion peut s’expliquer par des similitudes entre la mythologie tahitienne et l’arrivée des européens. Dans ce contexte, contraindre les jeunes filles à l’acte sexuel apparaissait pour les chefs comme une manière de satisfaire ces êtres d’essence divine pour s’en attirer les faveurs tout en capturant un peu de leur pouvoir en poussant les jeunes filles à tomber enceintes. En effet, dans la société tahitienne seul le premier né possède la force des parents.40 Si le malentendu est regrettable et qu’il est aisé d’imaginer l’aubaine que cela a pu représenter pour des marins n’ayant pas fait escale depuis plusieurs mois, les récits de voyage traduisent toutefois une tentative de compréhension de “l’incommensurable étrangeté des requêtes sexuelles de la société tahitienne”. Pour tenter d’expliquer les événements qu’ils vivaient, les Européens ont fait appel à leurs propres références culturelles puisant tour à tour dans la mythologie gréco-romaine, les récits bibliques et les topoï du libertinage (tels que présentés dans la littérature de Sade ou Prévost).41 Ce mélange a contribué à construire un fantasme dont se sont nourris et qu’ont continué à alimenter des générations d’européens.

Ainsi, l’histoire de la rencontre entre l’Europe et Tahiti repose sur un double malentendu, chaque civilisation ayant tenté de comprendre l’Autre à travers le prisme de ses propres référents culturels. De fait, la société pitcairnaise s’est construite sur la base non de la culture tahitienne mais d’une interprétation européenne de cette culture, faisant de ce qui aurait dû rester un événement exceptionnel, une norme sociale.

Margot Kreidl

Cover picture: Robert Dodd, 1790, The Mutineers turning Lieut Bligh and part of the Officers and Crew adrift from His Majesty's Ship the Bounty.. London, National Maritime Museum.

1 France inter. Tahiti et les révoltés de la Bounty, Tahiti et les révoltés de La Bounty (radiofrance.fr), accessed on 12/11/2022.

2 They were left with a barrel of water and food and achieved a feat: they rowed for 41 days and covered 6,000 km to reach the eastern colony of Timor. From there they returned to England where they were welcomed as heroes.

3 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr), accessed on 12/11/2022.

4 France culture. Pitcairn, 50 habitants, enjeu de puissance britannique au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, 50 habitants, enjeu de puissance britannique au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr)

5 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

6 BLAKEMORE, E., 2021. “La véritable histoire des révoltés du Bounty”. National Geographic. La véritable histoire des révoltés du Bounty | National Geographic , accessed on 12/11/2022.

7 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

8 BLAKEMORE, E., 2021. “La véritable histoire des révoltés du Bounty”. National Geographic. La véritable histoire des révoltés du Bounty | National Geographic , accessed on 12/11/2022.

9 France inter. Pitcairn et les descendants des révoltés du Bounty, Pitcairn et les descendants des révoltés du Bounty (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

10 ASSIER-ANDRIEU, L., 2012. “Le crépuscule des cultures. L’affaire Pitcairn et l’idéologie des droits humains”. Droit et Société, no. 82, pp. 763-787.

11 France culture. L’Affaire Pitcairn, L’Affaire Pitcairn (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

12 An adventurer seeking to make his fortune, the beachcomber has become one of the archetypal figures of the Pacific along with the vahine.

13 France inter. Pitcairn et les descendants des révoltés du Bounty, Pitcairn et les descendants des révoltés du Bounty (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

14 ASSIER-ANDRIEU, L., 2012. “Le crépuscule des cultures. L’affaire Pitcairn et l’idéologie des droits humains”. Droit et Société, no. 82, pp. 763-787.

15 France culture. L’Affaire Pitcairn, L’Affaire Pitcairn (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

16 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

17 France culture. L’Affaire Pitcairn, L’Affaire Pitcairn (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

18 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

19 France culture. L’Affaire Pitcairn, L’Affaire Pitcairn (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

20 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

21 France culture. L’Affaire Pitcairn, L’Affaire Pitcairn (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

22 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

23 France culture. L’Affaire Pitcairn, L’Affaire Pitcairn (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

24 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

25 France culture. L’Affaire Pitcairn, L’Affaire Pitcairn (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

26 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

27 ASSIER-ANDRIEU, L., 2012. “Le crépuscule des cultures. L’affaire Pitcairn et l’idéologie des droits humains”. Droit et Société, no. 82, pp. 763-787.

28 Ibid.

29 France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr) , accessed on 12/11/2022.

30 GOUJON, O., 2021. Pitcairn, les révoltés du Bounty vont disparaître. Chevilly Larue, Max Milo.

31 GRAINDORGE, C., 2019. “Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu.” In CASOAR Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu – CASOAR │ Arts et Anthropologie de l’Océanie , accessed on 12/11/2022.

32 TCHERKEZOFF, S., 2005. “La Polynésie des vahinés et la nature des femmes : une utopie occidentale masculine”. Clio. Histoire, femmes et sociétés. no. 22, pp. 63-82.

33 GRAINDORGE, C., 2019. “Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu.” In CASOAR Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu – CASOAR │ Arts et Anthropologie de l’Océanie , accessed on 12/11/2022.

34 Ibid.

35 DE HAAS, A., 2014. “Les métaphores de la séduction dans les journaux des marins français à Tahiti en avril 1768”. Journal de la Société des Océanistes. no. 138-139, pp. 175-182.

36 GRAINDORGE, C., 2019. “Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu.” In CASOAR Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu – CASOAR │ Arts et Anthropologie de l’Océanie , accessed on 12/11/2022.

37 DE HAAS, A., 2014. “Les métaphores de la séduction dans les journaux des marins français à Tahiti en avril 1768”. Journal de la Société des Océanistes. no. 138-139, pp. 175-182.

38 SAHLINS, M., 1989. Des îles dans l’Histoire. Paris, Seuil.

39 TCHERKEZOFF, S., 2005. “La Polynésie des vahinés et la nature des femmes : une utopie occidentale masculine”. Clio. Histoire, femmes et sociétés. no. 22, pp. 63-82.

40 GRAINDORGE, C., 2019. “Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu.” In CASOAR Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu – CASOAR │ Arts et Anthropologie de l’Océanie , accessed on 12/11/2022.

41 DE HAAS, A., 2014. “Les métaphores de la séduction dans les journaux des marins français à Tahiti en avril 1768”. Journal de la Société des Océanistes. no. 138-139, pp. 175-182.

Bibliography:

- ASSIER-ANDRIEU, L., 2012. “Le crépuscule des cultures. L’affaire Pitcairn et l’idéologie des droits humains”. Droit et Société 82, pp. 763-787.

- BLAKEMORE, E., 2021. “La véritable histoire des révoltés du Bounty”. National Geographic. La véritable histoire des révoltés du Bounty | National Geographic, accessed on 12/11/2022.

- DE HAAS, A., 2014. “Les métaphores de la séduction dans les journaux des marins français à Tahiti en avril 1768”. Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 138-139, pp. 175-182.

- France culture. L’Affaire Pitcairn, L’Affaire Pitcairn (radiofrance.fr), accessed on 12/11/2022.

- France culture. Pitcairn, 50 habitants, enjeu de puissance britannique au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, 50 habitants, enjeu de puissance britannique au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr), accessed on 12/11/2022.

- France inter. Pitcairn et les descendants des révoltés du Bounty, Pitcairn et les descendants des révoltés du Bounty (radiofrance.fr), accessed on 12/11/2022.

- France inter. Tahiti et les révoltés de la Bounty, Tahiti et les révoltés de La Bounty (radiofrance.fr), accessed on 12/11/2022.

- France inter. Pitcairn, une île maudite au coeur du Pacifique, Pitcairn, une île maudite au cœur du Pacifique (radiofrance.fr), accessed on 12/11/2022.

- GOUJON, O., 2021. Pitcairn, les révoltés du Bounty vont disparaître. Chevilly Larue, Max Milo.

- GRAINDORGE, C., 2019. “Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu.” In CASOAR Les Lumières à Tahiti ou l’histoire d’un tragique malentendu – CASOAR │ Arts et Anthropologie de l’Océanie, accessed on 12/11/2022.

- MÉTRAUX, A., 1964. “Les révoltés de la “Bounty” cent cinquante ans après. L’Homme, 4 (2), pp. 33-48.

- SAHLINS, M., 1989. Des îles dans l’Histoire. Paris, Seuil.

- TCHERKEZOFF, S., 2005. “La Polynésie des vahinés et la nature des femmes : une utopie occidentale masculine”. Clio. Histoire, femmes et sociétés, 22, pp. 63-82.