* Switch language to english for english version of the article *

I would like to thank Crispin Howarth for his time, answering these questions about Tā Moko: Māori Markings and his willingness to share his knowledge.

Curator for Pacific Arts since 2007 at the National Gallery of Australia, Crispin Howarth has curated a number of exhibitions over the past 12 years. Born in the Wirral, UK, Howarth began his interest in the art and cultures of the Pacific from visiting the comprehensive displays of the Liverpool Museum (now World Museum) and by living near Antique dealers who took the time to share their knowledge of objects from far away places, Tibet, Africa, Polynesia, Australia with him as a young child. From this beginning Howarth moved to Australia to be closer to Melanesia. Māori Markings: Tā Moko is his fifth exhibition for the National Gallery, it opened March 23rd and runs until 25th of August 2019.

Left: Alfred Burton, Te Hau Hau, at Te Kāiti, King Country 1885. Albumen silver photograph National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 2006.

Right: Joseph Jenner Merrett, Māori girl in cloak, 1845, pencil, watercolour, National Library of Australia, Canberra, Rex Nan Kivell Collection.

Clémentine Débrosse: How and why did you decide to work on Māori Markings: Tā Moko and create the exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia? Was it linked to a specific group of objects you had in the collection?

Crispin Howarth: This exhibition was born out of a much larger project that proved to be far too ambitious – an exhibition of Māori arts spanning from the pre-contact period up to the contemporary arts being created today. Such an exhibition would have required a much longer research and development period of several years to do such a wide scope justice, plus a far larger budget. The current exhibition was but one aspect of this larger exhibition proposal which was subsequently proposed as a focussed exhibition and agreed to by the Director in November 2017. The exhibition was less linked to the collection of the National Gallery of Australia than it was to the vast wealth of art from New Zealand’s colonial era of the 19th century. It is surprising how much historical art and archival documentation relating to Māori culture is held here in Australian institutions such as the National Library of Australia and elsewhere.

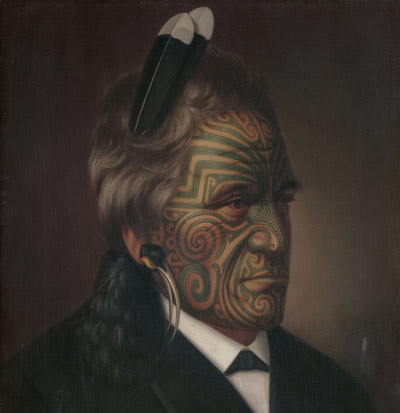

Gottfried Lindauer, Tomika Te Mutu, chief of the Ngāi Te Rangi tribe, Bay of Plenty, 1880, oil on canvas, National Library of Australia, Canberra, Rex Nan Kivell Collection.

CD: Did you work in collaboration with New-Zealand and Maori people?

CH : From the outset, it was my intention that such an exhibition could only be done with the active support of members of the Māori community who are the knowledge keepers regarding this art form. Through the auspices of the umbrella organisation Toi Māori Aotearoa (a charitable trust promoting Māori traditional arts and Māori artists) I was able to work with members of Te Uhi a Mataora the peak body concerned with the art and practice of Tā Moko today.

Without their collaboration the exhibition would have been, bluntly put, soulless and without a sense of purpose. Through consultation and conversations with members of Toi Māori and Te Uhi a Mataora today’s living art of moko (Tā moko being the process and moko being the worn art as skin markings) and its historical backdrop through colonial visual documentation really became alive to me. The strands of knowledge either as a little known watercolour from the 1840s sitting in a Museum’s collection or as knowledge shared by members of Te Uhi Mataora I can only liken to the weaving of a cloak, slowly what were, in the first instance, quite disparate fragments of understanding were pulled together to form the exhibition and the especially the researching that underpins the accompanying catalogue.

Left: Feeding funnel, Muriwhenua Region, Aotearoa, Before 1793,

South Australian Museum, Adelaide. © Photographie : Crispin Howarth.

Right: Warrior Chief Te Rauparaha, fixed in his canoe, Māori, Aotearoa New Zealand, southern Polynesia, c 1835, wood, 43.5cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

© Photographie : Crispin Howarth

CD: From which collections are the objects presented in the exhibition?

CH: The exhibition is relatively small at approximately fifty works, with the limitation a small exhibition has, I sought loans domestically here in Australia but with good fortune two private loans of both 19th century and 21st century photography from New Zealand where also secured. The majority of the works on display come from the National Library of Australia, particularly the exceptionally rich Rex Nan Kivell collection. This is a collection (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rex_Nan_Kivell) of unparalleled depth which has yet to be fully realised by Pacific scholars. Alongside the paintings, illustrations and photography are also a selection of Taonga in the form of Whakairo. The Gallery’s Poutokomanawa figure stand at the entrance to the exhibition, there is the feeding funnel, Korere, given to Australia’s first Governor, Philip Gidley King, in 1792 which represents on the earliest items of Taonga in the world after the material collected in Cook’s voyages. Perhaps the most phenomenal work is the Self-portrait bust by Hongi Hika who carved his moko’ed faces upon a piece of wood whilst in Sydney in 1815.

Exhibition space: Tā Moko. © Photograph: Crispin Howarth

CD: Do you see Māori Markings: Tā Moko as a way to explain the real meaning of Ta moko and the importance of words where Europeans usually use the word Tattoo?

CH: The exhibition’s working title was ‘Tā moko is not tattoo’. There are certainly clear differences between both; to wear moko is to walk with integrity, you cannot receive the moko without being ready spiritually and considered ready by your peers. There is a far deeper level of understanding at play, there is a framework of principles (Kaupapa) that envelops the process. Moko are marks of pride for family and of connectedness to a larger community. A mere tattoo in the western sense seems very facile in comparison. Words are important. The word tattoo comes out of the Polynesian ‘Tatau’ and, operatively it is generally a great descriptor but for the art of Tā Moko in the mind’s eye of our visiting audience, the word ‘tattoo’ comes loaded with preconceptions, especially with older visitors.

Serena Stevenson, Naboua Nuku, Hori (George) Tamihana Nuku and Haki Williams, (detail) 2002.

CD: Do you see the differentiation in the vocabulary between Tā Moko and Tattoo as an act of decolonization?

CH: Less the differentiation of these words which I have address earlier, however, this exhibition project from the outset was about placing Maori first and foremost as best as I could regarding the tyranny of distance, time and funding. With the Carte de Visites, paintings and sketches made by visitors or settlers to New Zealand in 18th and 19th century such as Sydney Parkinson or Joseph Jenner Merrett museums and art galleries quite rightly place them at the top of the pile in terms of information to be disseminated to the audience and the person within the created image is sadly placed in a passive role. Broadly speaking, all images of Māori ancestors (Tipuna) are considered to be alive in certain respects, a continuation of their spirit if you will, and deserve recognition by their descendants. With Māori Markings: Tā Moko, the emphasis was upon the person in the image, photograph or represented in sculpture. To that end you will see in the catalogue for example the individual depicted is privileged over the recording artist – for example, the 1773 image by Sydney Parkinson titled ‘The head of a New Zealander, with a comb in his hair, an ornament of green stone in his ear, and another of a fish's tooth round his neck’ has an incredibly boring title yet descriptive title, which, no one viewing the image need to read if they look at the image itself. With research and to put Māori first and foremost, the title of this work for this exhibition becomes Te Kuu Kuu - name of the person in the image. The accompanying information is about that person and their moko. The foreign artist (poor Parkinson who died of dysentery during his Pacific voyage) is of less concern in this particular exhibition as the goal was to place the wearer of moko shown in the image to the forefront of focus.

Another part of the exhibition which one might consider an act of decolonization was the active practice of Tā moko in the exhibition space. This was important to continue the connections of the past with the present into the future, several people received moko and a short documentary can be found here.

Brent Kerehona receiving moko from Te Rangi Kipa during the opening weekend.

Courtesy Kris Kerehona

CD: What performances did you bring around the Māori Markings: Tā Moko exhibition and to what extent are they an additional value?

CH : Lorsque l’on travaille avec des arts quels qu’ils soient, il est important d’apprendre, de comprendre et d’appliquer les protocoles indigènes appropriés. À cet égard, l’exposition ne faisait pas exception. À la demande des membres de la communauté, une œuvre précise a reçu une bénédiction particulière et, lors du vernissage de l’exposition, une série d’évènements se sont déroulés. Tout d’abord des représentants de la communauté aborigène locale ont rencontré la délégation Māori afin de demander la permission d’entreprendre les activités liées à l’exposition sur les terres aborigènes. Dans un deuxième temps, il y a eu une cérémonie d’enfumage afin de souhaiter la bienvenue sur les terres aborigènes à la délégation Māori qui ont, à leur tour, conduit une procession cérémonielle jusqu’à la National Gallery et dans les espaces d’exposition afin de s’assurer que tous les objets de l’exposition reçoivent l’attention rituelle appropriée.

Sans cette cérémonie et d’autres évènements liés à l’exposition et la collection de la National Gallery, ce serait un euphémisme de dire que quiconque y ayant assisté en est reparti avec des souvenirs inoubliables.

Clémentine Débrosse

Article traduction: Clémentine Débrosse et Béatrice Bijon.

Image à la une : Vue de l’espace d’exposition. © Photographie : Crispin Howarth

Plus d’information sur l’exposition : https://nga.gov.au/tamoko/

Le catalogue de l’exposition : https://shop.nga.gov.au/exhibition-catalogues/maori-markings-ta-moko