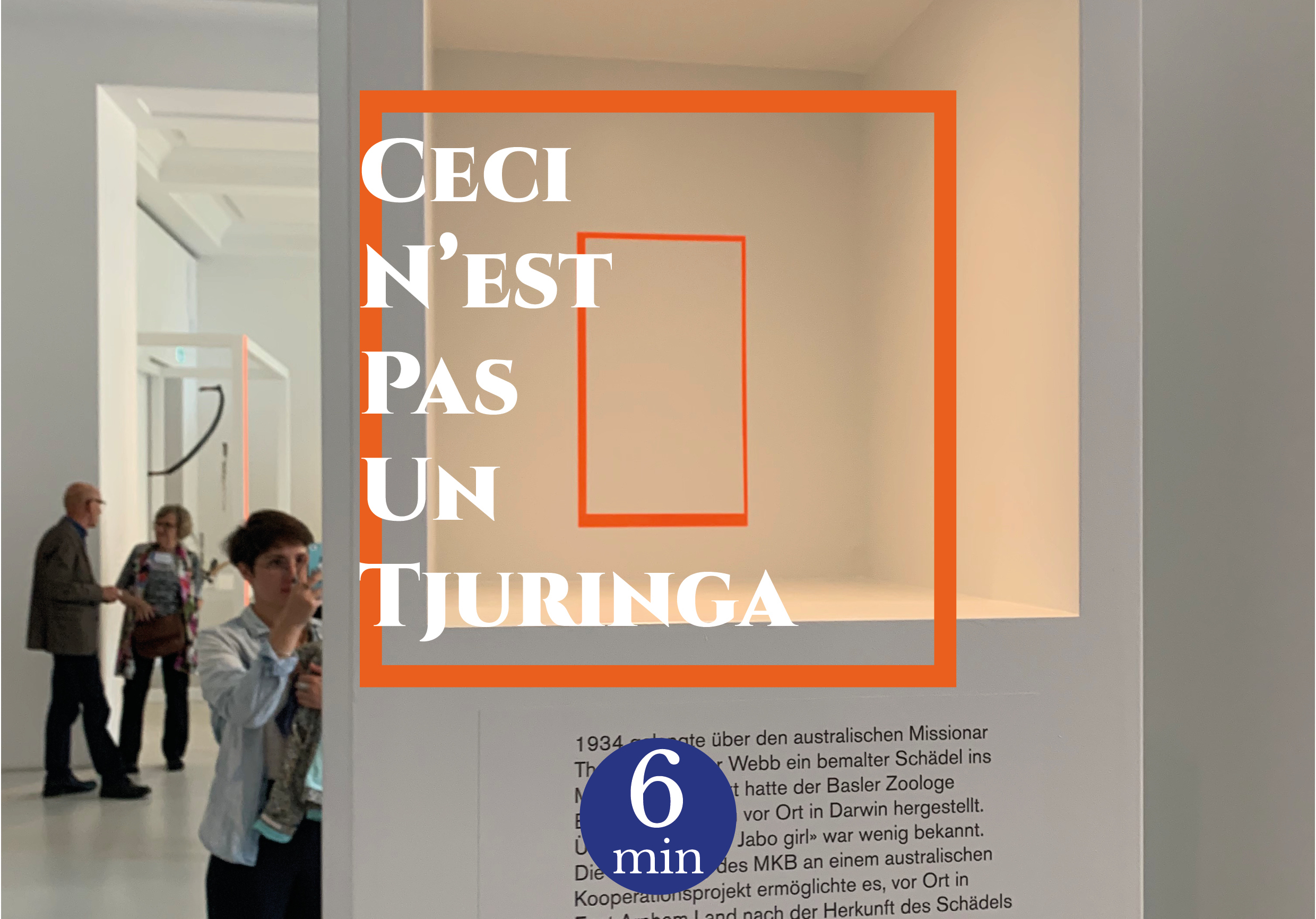

If you have the opportunity to visit the exhibition Thirst for Knowledge Meets Collecting Mania at the Museum der Kulturen in Basel,1 you will certainly be curious about the presence of an orange rectangle in one of the showcases, in which no objects are displayed. At first glance, you might think that this absence is due to a restoration problem, a loan that did not arrive in time, in short a technical problem. If you look closely, it actually says on the label that the object in question will not be on display, as it cannot be seen by everyone.

The curators have decided to question the museographic practices related to the sacredness and secrecy of so-called "sensitive" objects, in order to respect the provisions of the original peoples concerning what can or cannot be done with the collections. The object missing from the display case in the Museum of Cultures is a tjuringa, a flat, elongated stone or wooden element 10 to 40 cm long, with engraved designs, sometimes wrapped in various elements, including hair.2 Tjuringa have a key place in the cosmogony of the Arrernte people who live in the Central Australian Desert.

Today's article is dedicated to these tjuringa in order to understand more precisely why exhibiting certain things in museums can be felt as an offence to the people related to them. We will talk about things rather than objects. Because the vocabulary we use is also extremely important. When you are told "object", don't you think directly of something inert, summed up in its materiality, most certainly created by Man to meet his needs, as the opposite of the acting and thinking subject? Whereas a thing, in the common imagination, is more alive, it can act, it is not necessarily dominated by human will. This point of vocabulary may seem anecdotal to you, but in reality, changing the vocabulary used allows us to have a new approach to what we are studying. Indeed, the notion of thing allows us to go beyond a certain dualism that has stuck to European culture since Cartesian thought: that which separates the body and the mind but also that which separates the object and the subject. As Tim Ingold points out, Aristotle's so-called hylemorphic thinking, which separates the element of form from the element of matter, has the consequence of considering form as imposed on matter and objects as passive and shaped by humans.3 Talking about thing thus allows us to extend the field of possibilities of what we consider to be alive or to have a possibility of action.

Returning to the tjuringa, they are seen as parts of the bodies of ancestors or mythical beings, left in the landscape as their trace and material presence.4 Their liminal, i.e. intermediary, status between mythical beings and humans and between the past and the present, makes them essential bridges between the world of the present and the Dreaming. Alchera, translated by Westerners as "Dream time" or "Dreaming" corresponds to the Arrernte cosmological organisation. It is in a way the organising process of the world, which links beings together. The interpretation of Alchera and its association with the notion of 'dream' has, however, been criticised. Marika Moisseeff, for example, proposes instead the idea of 'spatial dynamism', which implies not only that it is something in motion but also that it constantly creates and reorganises space.5 Tjuringa have an important role in this 'spatial dynamism', because they are parts of the mythical beings and because they create the link with humans. They are a physical presence of the immaterial 'dream time'. They are involved in initiations, but also in the maintenance of fertility and mediate between all ritual participants, and each tjuringa is linked to a particular initiate.6 Young men, during initiation ceremonies, are brought into the presence of their own tjuringa. Non-initiates, i.e. children and women, cannot attend these ceremonies and cannot see the tjuringa. Barbara Glowczewski therefore proposes that tjuringa are 'spiritual and geographical identity cards' because they mark the relationship of the person with his or her environment as well as with his or her territory.7 As the anthropologist Carl Strehlow has pointed out, tju means something secret and shameful and runga means one's own.8 This translation helps us understand why tjuringa are so important and personal, since a tjuringa is linked to an initiate and can only be shown to very specific people at the time of initiation. One can imagine the vulnerability of initiates when tjuringa are exposed to the public eye.

More generally, the term tjuringa applies to what is 'sacred'. Thus, names given to initiates or certain songs and ceremonies may be tjuringa.9 Moreover, they are linked to what has been translated as 'child-spirits', the ngantja, who are like parts of mythical beings and who will occupy the tjuringa until they enter a woman's womb. As anthropologist John Morton points out, 'each tjuringa is connected to a single ancestor and contains his [spirit], (ngantja) and each is capable of incarnating into the body of a person'.10 In addition to being connected to men and ancestors, tjuringa are also connected to the land, as they are kept in very secret places, linked to the travels of mythical beings, which are only known and accessible to certain initiates. For all the reasons mentioned above, we realise that the tjuringa, which to an outsider may be characterised by their materiality and inertia, are in fact connected to the living and in constant interaction with it. For this reason, tjuringa cannot be considered as mere 'objects' but rather as 'things', capable of action, as mentioned above. We understand that the distinction between object and subject is culturally relative and that the interactions of a certain population with its environment vary from one culture to another.

This is where the responsibility of researchers and museums comes into play, like with the Museum der Kulturen in Basel mentioned at the beginning of this article. The curators have decided not to show tjuringa because they are aware of the extremely offensive effect it can have on the people connected with them and they respect the importance of these things. Many museums are removing tjuringa from their display, deleting the images from their databases and initiating research into their provenance, also in order to know how to handle the collections in the storerooms. As heirs to collections that were often acquired without the consent of their original owners, museums have a role to play in the dialogue that is currently being initiated, in order to have a respectful approach to these so-called 'sensitive' collections. The exhibition Thirst for Knowledge Meets Collecting Mania shows that it is possible to inform the public about these issues and about this colonial heritage. It affirms a choice not to show certain things, for reasons of respect and ethics. The same applies to research, which in its methodology and vocabulary can have the effect of sweeping aside or missing the concerns and claims of the people concerned. It is for this reason, for example, that the sociologist Emile Durkheim, in his analysis of the data reported from several fieldwork sites in the Central Desert, particularly among the Arrernte, has been criticised in retrospect.11 Indeed, Barbara Glowczewski, in her article Replaying anthropological knowledge, from Durkheim to the Aborigines, questions the validity of the sociologist's dualistic analyses and his classificatory approach, linked to religion, which is specific to his time but which does not allow for an understanding of the complexity of the Arrernte value system.12 Beyond discussing an erroneous analysis, Glowczewski also worries about the institutionalisation and authority of Durkheim's thinking. This results in the erasure of Arrernte voices on their own traditions and in their attempt to define themselves and not from outside. It is for this reason that Pacific authors and intellectuals such as Linda Tuhiwai Smith call for the 'decolonisation of research',13 the adaptation of methods to the perspective of the 'studied' populations, so that the exchange made is no longer one of domination and data extraction on the part of the European researcher, but one that is two-way and useful to all. This decolonisation is necessary in the case of the tjuringa, in order to adapt museological principles as well as the rules of the art market, with a view to making amends for past mistakes and to a more respectful museum practice.

Margaux Chataigner

Image à la une : Vitrine présentant un tjuringa sans le montrer, Bâle, Musée des Cultures, exposition « La quête du savoir rencontre la soif de collectionner », Septembre 2020.

© photographie Clémentine Débrosse.

1 The exhibition is opened until 22 novembre 2020.

2 MOISSEEFF, M., 1994. « Les objets cultuels aborigènes : ou comment représenter l’irreprésentable». Genèses, no.17, p. 19.

3 INGOLD, T., 2010. “Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials”. Realities, University of Manchester, working paper #15, p.1.

4 TESTART, A., 1993. « Des Rhombes et des tjurunga. La question des objets sacrés en Australie». L’Homme no. 125, XXXIII, p. 49.

5 MOISSEEFF, M., 1994. « Les objets cultuels aborigènes : ou comment représenter l’irreprésentable». Genèses, no.17, p. 16.

6 Ibid, p. 29.

7 GLOWCZEWSKI, B., 2001. “Culture Cult. Ritual Circulation of Inalienable Objects and Appropriation of Cultural Knowledge (Northwest and Central Australia).” In JEUDY-BALLINI, M. et JULLIERAT, B., (eds.) People and things – Social Mediation in Oceania. Durham, Carolina Academic Press, p. 270.

8 MOISSEEFF, M., 1994. « Les objets cultuels aborigènes : ou comment représenter l’irreprésentable». Genèses, no.17, p. 19.

9 TESTART, A., 1993. « Des Rhombes et des tjurunga. La question des objets sacrés en Australie». L’Homme no. 125, XXXIII, p. 46.

10 MORTON, J., 1987. “Singing Subjects and Sacred Objects: More on Munn’s Transformation of Subject into Object in Central Australian Myth”. Oceania, vol. 58, no. 2, p. 112.

11 In Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse, Durkheim analysed in 1912 the data that had been collected about Aboriginal Australians, particularly through the early 20th century writings of Spencer and Gillen on the Arrernte people and other groups in Central Australia.

12 GLOWCZEWSKI, B., 2014. « Rejouer les savoirs anthropologiques : de Durkheim aux Aborigènes». Horizontes Antropológicos, Porto Alegre, no. 41, p. 386.

13 TUHIWAI SMITH, L., 2008 (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies. Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books, London.

Bibliography

- GLOWCZEWSKI, B., 2001. “Culture Cult. Ritual Circulation of Inalienable Objects and Appropriation of Cultural Knowledge (Northwest and Central Australia).” In JEUDY-BALLINI, M. et JULLIERAT, B., (eds.) People and things – Social Mediation in Oceania. Durham, Carolina Academic Press, pp. 265-288.

- GLOWCZEWSKI, B., 2014. « Rejouer les savoirs anthropologiques : de Durkheim aux Aborigènes». Horizontes Antropológicos, Porto Alegre, no. 41, pp. 381-403.

- INGOLD, T., 2010. “Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials”. Realities, University of Manchester, working paper #15.

- MOISSEEFF, M., 1994. « Les objets cultuels aborigènes : ou comment représenter l’irreprésentable». Genèses, no.17, pp. 8-32.

- MORTON, J., 1987. “Singing Subjects and Sacred Objects: More on Munn’s Transformation of Subject into Object in Central Australian Myth”. Oceania, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 100-118.

- TESTART, A., 1993. « Des Rhombes et des tjurunga. La question des objets sacrés en Australie ». L’Homme, no. 125, XXXIII, pp. 31-65.

- TUHIWAI SMITH, L., 2008 (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies. Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books, London.

Pingback: Bibliographie en cours sur le thème de la restitution | Bildungsblog