Christian missions were involved very early in the history of colonisation in the Pacific. From the end of the 18th century, the conversion of local populations was a major challenge for the Western churches. It was seen as a divine mission: to "save" the souls of the "pagans" from the clutches of false divinities. Evangelisation, which was closely associated with the colonial process, was carried out by large religious organisations, such as the London Missionary Society in Polynesia and the Catholic Church through the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in Mangareva, as well as by a multitude of lesser-known missions, often stemming from Protestant currents of Christianity. Among these, one church in particular has left its mark on the history of the Solomon Islands archipelago to this day: the South Sea Evangelical Mission.

First of all, a quick look at the definition of Christianity. Or rather ChristianitieS. Although we tend to speak of it in the singular, Christianity is very far from being a unified religion, and it comprises many currents that are profoundly at odds with one another. There are three main streams: Catholicism, Protestantism and Orthodoxy. We will leave aside the latter, which has not taken root in the Pacific, and focus on the main differences between the first two. Protestantism emerged from the Reformation, a movement that took place in the 16th century under the impetus of a number of theologians, including Martin Luther and John Calvin. In their writings, they expressed their disagreement with what they perceived as the excesses of the Catholic Church, particularly its material wealth, but also with a number of fundamental issues. Under their impetus, a split was created between two movements: Catholics and Protestants. The Protestants rejected the authority of the Pope and the idea that priests had a privileged relationship with the divinity over other members of the faithful. Other concepts such as the cult of the saints and the existence of purgatory were also called into question. Generally speaking, Protestantism advocates a return to the Bible as the first and principal source of knowledge of the divine, accessible to all believers: this is known as sola scriptura.

Map of the Solomon Islands. © CASOAR

Catholicism and Protestantism are obviously not themselves totally unified movements. While Catholicism benefits from a certain institutional stability through the existence of a strong hierarchy, dominated by Rome and the figure of the Pope, God's representative on earth, Protestantism is marked by a phenomenon that sociologists call "Protestant precariousness".1 In Protestantism, the church as an institution is not considered to be sacred or to possess absolute authority, nor are pastors invested with any particular sacredness. A difference of interpretation of the Scriptures may well lead a member of a church to leave and found a new congregation of which he is the pastor. There are therefore a multitude of Protestant churches and movements, some of which are extremely different and vary greatly in size.

Among these major trends, one term that often comes up is evangelicalism. This word is frequently used to describe very diverse churches that are often in conflict with each other and in no way constitute a unified movement. Rather, evangelicalism is taken to mean a certain number of trends or concepts shared by these churches despite their differences.2 So-called evangelical movements generally consider the Bible to be the only source of truth and very often a historical document. They also place the figure of Christ, his death and his Resurrection at the centre of their doctrines and place particular emphasis on the importance of conversion, which they consider to be the only way to salvation. These movements are therefore very active in their proselytism. It is not unusual for them to adopt a political stance, as can be seen in the United States.

Florence S.H. Young

And it was in one of these evangelical churches that Florence Young, the future founder of the South Sea Evangelical Mission, was born in 1856.3 Raised in Victorian society, she grew up between New Zealand, England and Australia, where her brothers eventually established a sugar cane plantation called Fearymead, "the fairy meadow". Quite the programme. The second half of the 19th century saw the economic expansion of the Australian colony, particularly following the discovery of precious metal deposits in the late 1830s. Numerous plantations were then established in the Queensland region. To be profitable, these plantations required a large and, if possible, inexpensive workforce.

And what could be cheaper than going directly to neighbouring archipelagos to source workers from populations unfamiliar with salaried work and with low expectations in terms of pay? So from the late 1940s onwards, recruiting ships began to sail around Melanesia, in particular the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, which were not yet claimed by any Western state as colonies. These ships were responsible for "negotiating" the enlistment of workers for three years on Australian or Fijian plantations. In practice, the men were sometimes simply deceived or even abducted by force, which led to this method being described as blackbirding and likened to the practice of slavery. In the middle of the 19th century, there was no law regulating the recruitment or employment of Pacific peoples in Australia. Although legislation was gradually introduced to limit abuses and set minimum wages and better working conditions, blackbirding continued in practice until the early 20th century. Wages remained low, working conditions difficult, and at the end of the three years, the ships had the unfortunate tendency to take the men back to the wrong place in the archipelago to save time, thereby putting them in danger.4 Conflicts between recruiters and local populations were not uncommon and were generally met with violent repression by the colonial authorities. For all these reasons, blackbirding has been a traumatic experience and a major factor in social change in the societies affected. It also played a very important role in the conversion of these societies to Christianity.

While visiting the family plantation, Florence Young then aged 26, decided to set up a Sunday school to teach the employees the principles of Christianity. To do so, she used Pijin, a Creole language created from a mixture of English and Melanesian languages, which enabled the men working on the plantations to communicate despite having very different mother tongues. Florence Young's enterprise met with some success and in 1886 led to the foundation of a full-scale mission: the Queensland Kanaka Mission (QKM).5

QKM was not affiliated to any church and was entirely voluntary, financed by external donations. The few members of the QKM saw their work as a divine mission. Florence Young herself described her arrival at Fearymead in these terms: "God put me in contact for the first time with men and women who had never heard of Christ and for whom nothing was being done to teach them the way to salvation. And that seemed horrible to me. [...] Surely God wanted us to do something about it."6 The aim of the QKM was therefore clear: conversion at all costs, everything else being considered largely superfluous. At the end of the 19th century, the mission grew and spread to other plantations in the region, but in 1901, the government published the Commonwealth Restricted Immigration Act, which prohibited the use of foreign workers and obliged planters to repatriate all their employees by 1906. The QKM thus lost its raison d'être, but a new question arose for the mission: how could evangelisation continue once the converts had returned to their archipelago of origin?

The fate of new Christians is also a matter of concern. With recommendations from the mission, converts from Vanuatu have the opportunity, on their return, to join one of the churches already established there. But for those from the Solomon Islands, things are a little more complex. Very few churches are already present in the archipelago and the QKM fears for the safety of converts, who risk being ostracized by their society, but also, and above all, for their faith, which they might be tempted to abandon once they are back in contact with their former religion. It is important to understand that for the QKM, the question of salvation takes precedence over that of physical safety.

To find out how the QKM became one of the most important churches in the Solomon Islands today, check out our next article!

Alice Bernadac

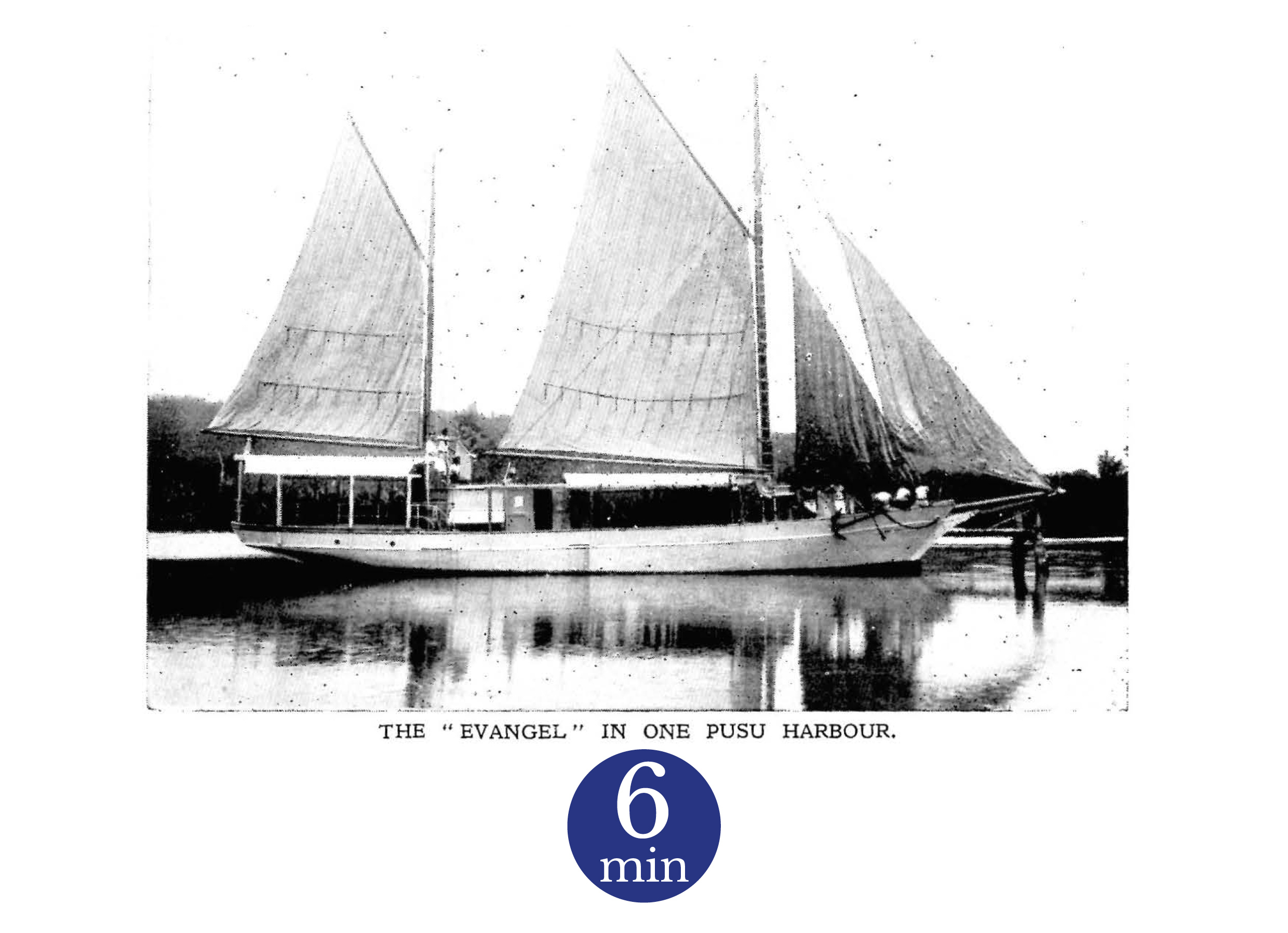

Cover Picture: The Evangel, the mission ship

1 On these questions see: WILLAIME, J.-P., 1992. La Précarité Protestante. Sociologie du Protestantisme Contemporain. Genève, Labor et Fides.

2 COLEMAN, S. & HACKETT, R. (éds.), 2015. The Anthropology of Global Pentecotalism and Evangelicalism. New York, New York University Press.

3 On the biography of Florence Young see: YOUNG, F., 1925. Pearls from the Pacific. London, Edinburgh, Marshall Borthers, Ldt.

4 On the history of blackbirding see chapter 3 of LAWRENCE, D., 2014. The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. Canberra, ANU Press. As well as BENNETT, J., 1987. Wealth of the Solomons. A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978. Honolulu, Pacific Islands Studies Program, Center for Asian and Pacific Studies, University of Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press.

5 HILLIARD, D., 1969. « The South Sea Evangelical Mission in the Solomon Islands. The Foundation Years », The Journal of Pacific History. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, pp. 41- 64.

6 YOUNG, F., 1925. Pearls from the Pacific. London, Edinburgh, Marshall Borthers, Ldt, p.47.

Bibliography:

- BARKER, J., 1990. Christianity in Oceania. Ethnographic Perspectives. Lanham, New York, University Press of America.

- BENNETT, J., 1987. Wealth of the Solomons. A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978. Honolulu, Pacific Islands Studies Program, Center for Asian and Pacific Studies, University of Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press.

- BURT, B., 1993. Tradition and Christianity : the Colonial Transfomation of a Solomon IslandsSociety. Chur, Switzerland, Philadelphia, Hardwood Academic Publishers.

- COLEMAN, S & HACKETT, R. (éds.), 2015. The Anthropology of Global Pentecotalism

and Evangelicalism. New York, New York University Press. - DECK, J.-N., 1945. South from Guadalcanal. The Romance of Rennell Island. Toronto,

Envangelical Publishers. - GRIFFITHS, A., 1977. Fire in the Islands ! The Act of the Holy Spirit in the Solomon. Wheaton,

Harold Shaw Publishers. - HILLIARD, D., 1969. « The South Sea Evangelical Mission in the Solomon Islands. The

Foundation Years », The Journal of Pacific History. Melbourne, Oxford University Press,

pp. 41- 64. - LAWRENCE, D., 2014. The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. Canberra, ANU Press.

- WILLAIME, J-P, 1992. La Précarité Protestante. Sociologie du Protestantisme Contemporain. Genève, Labor et Fides.

- YOUNG, F., 1925. Pearls from the Pacific. London, Edinburgh, Marshall Borthers, Ldt.