*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

How can I describe a father’s suffering who is separated from his wife and children for six years?

How can I describe a mother witnessing her small kids growing up for six years in a prison camp?

How can I describe a young man who was full of life but has lost his opportunity to continue his education, to find love, has lost his health, his family, his hope, has lost many opportunities that you take for granted?1

Behrouz Boochani, TedxSydney Writing is an act of resistance.

Behrouz Boochani, a Kurdish journalist became the voice and face of resistance against Australian migration politics. Through different press articles, book and movie, he offers a strong and intimate counter-narrative to the official Australian discourse on illegal immigrants. He realised in 2017 the movie Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time with Arash Kamali Sarvestani, a Dutch-Iranian filmmaker. The following year, Boochani published his book, No Friend but the Mountainsresult of his work with his translator, Omid Tofighian, an Iranian-Australian philosopher. Both works were made possible thanks to mobile phones smuggled into the prison (offshore processing centre). The book was written and sent via WhatsApp to Omid Tofighian and images were recorded and sent to Arash Kamali Sarvestani. The movie depicts the story of Boochani, an imprisoned journalist and his relation with Janet Galbraith, an Australian journalist. She asks Boochani to provide her documents and evidence on a prison cell called Chauka (which is also the name of a local bird). In this search of evidence, images and sounds provide another way to represent the pain and suffering imposed by the prison and its ideology. With regard to the book, the narrative unfolds in a broader timeline. The reader follows Boochani from Indonesia to his attempts to join Australia on rickety boats. He is then captured and detained for a month in Christmas Island before being sent to Manus prison where he stayed for six years. Both projects were widely praised by the general public and academic circles. The movie toured in festivals and the book won in January 2019, the Victorian Prize for Literature and the Victorian Prize for Non-Fiction, Australian highest literary awards.

Manus prison, or what is known by the Australian government as Manus Regional Processing Centre, is located on Los Negros Island in Manus Province, Papua New Guinea. Even if the territory is part of Papua New Guinea, independent since 1975, Australian authorities manage this centre since 2001. The other “offshore processing centre” is on the island of Nauru, in Micronesia. Both countries of Nauru and Papua New Guinea are economically dependent on Australia. Since 1992, all “unauthorised” asylum seekers are removed from public consciousness by detaining them in these detention centres. In the history of Australian migration politics, the first policy was The Pacific Solution by John Howard’s government in 2001. At that time, the “centres” of Nauru and Manus were established. The indefinite detention of all asylum seekers - including women and children - arriving in Australia is justified by the Migration Act 1958. Through the mechanism of complex administrative and legislative measures, this indefinite detention is made possible and legal. During Kevin Rudd’s tenure (2007-2010), the detention of asylum seekers was stopped. The centres in Nauru and Manus were resumed in 2012 and 2013 under Julia Gillard’s government through a new migration policy, The Pacific Solution II. This policy was even stricter than the previous since the resettlement in Australia of those sent to Nauru and Manus was prohibited. Manus prison was shut down in October 2017 after the Papua New Guinea Supreme Court ruled the prison illegal. But the detainees were forcefully transferred to other centres on Manus Island. Boochani is now living in New Zealand but by June 2021, 125 detainees were still in Papua New Guinea and 108 in Nauru, living under highly precarious conditions.2

On top of the geographical remoteness from Australia, the detainees are also made invisible and unheard through media blackouts and information bans. In order to conceal the reality of these prisons, the Australian government create legal paraphernalia. Amendments were made in 2014 to the Australian Security Intelligence Organization Act 1979 against the freedom of the press regarding these prisons by prohibiting media reporting of “special intelligence operations.” Moreover, media were controlled through the enactment of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Act 2015. The government had new powers to ask for “journalist information warrants” so that telecommunications have to provide the metadata of journalists and reveal therefore their sources.3

The importance of Behrouz Boochani’s work is therefore even more important. He was able to make his voice and narrative heard and visible in the mainstream media in Australia and across the world. Both his book and his movie tackle the issues of representation of pain and suffering. How to represent his pain and suffering to an outside audience? This was the main struggle for Boochani. He wanted to avoid the pitfall of depicting his experience and the ones of his co-detainees as miserable, without agency, without power, without personhood and completely reduced to his current situation as an immigrant. This discourse and images of the Other suffering are mainly depicted by three “genres”: journalism, documentary photography and documentary movies. They create and circulate stereotypical images of asylum seekers as Others. Their language is intimately rooted in the power structures in which the Manus prison takes place.4 Both in his book and the movie, Boochani reveals the issues with the rationality of these genres. In the book, he particularly mentioned his problems with the journalists and the photographers on Christmas Island. The camera was used as a weapon, dominating and claiming ownership over their bodies. The camera materialises this imbalanced power relationship in which the refugee is reduced to the desire of the photographer to take a picture that “evokes the most heightened sense of compassion possible.”5 In this perspective, the identity and personality of the photographed subject do not matter. Boochani describes precisely this power of the camera to dehumanise the refugees. When transiting from Christmas Island to Manus prison, the photographers and journalists on the tarmac operate in the same way as the police officers.

"Pandemonium breaks loose at the airport. Dozens of police officers stand by the plane in military mode. A few journalists have their cameras ready. All of them are waiting for us. The interpreters are there, also. […] I can’t work it out; I can’t understand why they have to securitise that space. I am frightened by the journalists; I am frightened by the cameras they hold.

Journalists inquire into everything. They are always seeking out horrific events. They acquire fodder for their work from wars, from bad occurrences, from the misery of people. I remember when I used to work for a newspaper I would become agitated from listening to all the news about, for instance, a coup d’état, a revolution, or a terrorist attack. I would begin work with great fervour and scramble for that kind of research like a vulture; in turn, I fed the appetite of the people.

The journalists are staking out the situation like vultures: waiting until the wretched and miserable exit the vehicle; eager for us to come outs quickly as possible, to catch sight of the poor and helpless and launch on us -

Click, click/

Waiting to take their photos/

Click, click

- and dispatch the images to the whole world. They are completely mesmerised by the government’s dirty politics and just follow along. The deal is that we have to be a warning, a lesson for people who want to seek protection in Australia.”6

And the description goes on later pages:

I looked so debilitated. I was walking around as though my mind could no longer guide my legs. As I walked, I felt as though I was sitting on a boat swayed by tides. When we disembarked, those nosy journalists and their contemptible cameras bombarded us. I was too weak to put my hand up to cover my face. No doubt, the spectacle of travellers saved from drowning and miraculously reaching dry land was sensational subject matter.

This is the second time in a short period that we have become the objects of inquiry for these intrusive people. The airport on Christmas Island has become a studio for a photo shoot. It seems that they are waiting in ambush, waiting for the time they can see me helpless and fragile. They are waiting to make me subject of their inquiry. They want to strike fear into people with the movement of my possessed corpse.

[...] No matter who I am, no matter how I think, in these clothes, I have been transformed into someone else.

All this aside, how can I pass by all these cameras? In particular, these few young blonde women with a strange enthusiasm for taking photographs - and from such close range, from almost no distance at all. I shouldn’t show any weakness. I throw caution to the wind and exile the vehicle. The giants are waiting for me. They immediately lock biceps with my biceps and walk towards the aeroplane. I hold my head high - I take long steps - I want to end this painful scene as quickly as possible.

We get close to the journalists. One of the blonde girls takes some steps away and kneel down, taking a few artistic photographs of my ridiculous face. No doubt, she will create an excellent masterpiece which she can take back and show her editor-in-chief, and then receive encouragement for showing initiative. That thin body underneath this baggy, sloppy clothes - all from the point of view of someone positioned below the waist. And it really will be a brilliant piece of art. My head I hold up high, dignified, and I try to maintain that as I climb the steps to the plane. But my steps are more like the steps of someone trying to run away.”7

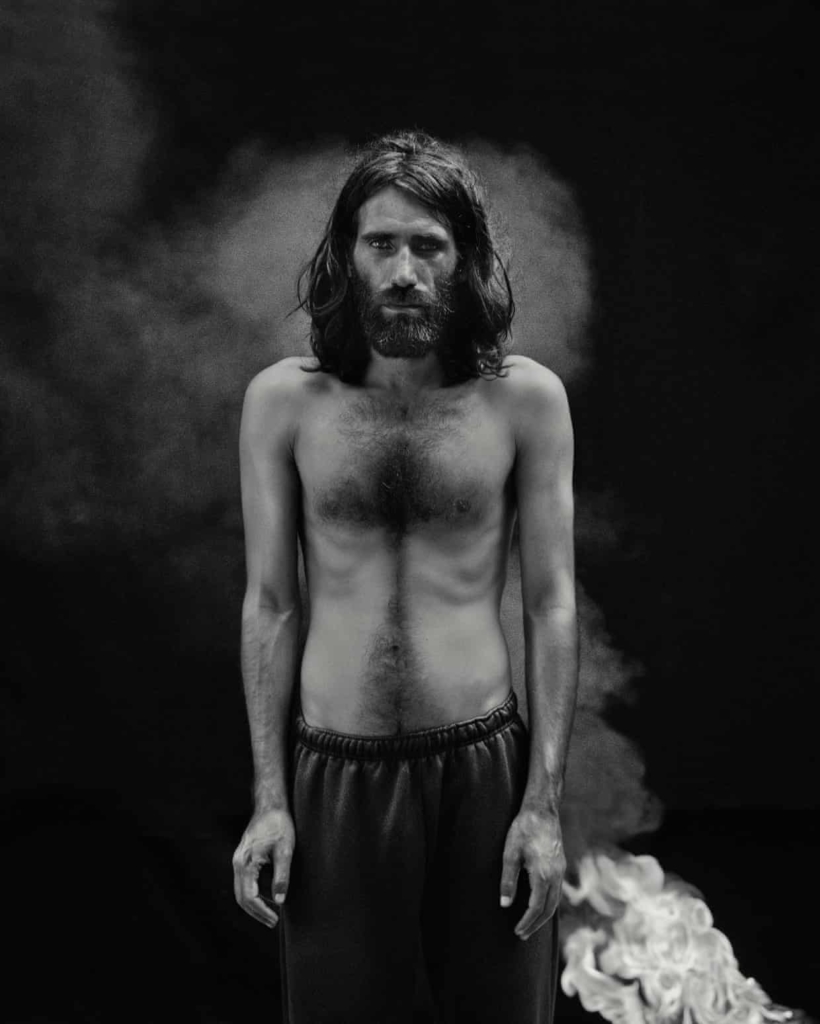

Portrait of Behrouz Boochani made at Manus Prison in 2018 by the photographer Hoda Afshar. The image won the Bowness Photography Prize the same year © Hoda Afshar

L’intrigue de Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time ’s plot also revolves around Boochani’s distrust of journalism. Being detained, he realises that the language of journalism based on evidence and documents cannot transcribe his experience in the prison. The prison and its ideology take place within a complex system which he calls “The Kyriarchal System”. The term kyriarchy was first coined by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza to denote interrelated social systems created for domination, oppression and submission.8 This particular system involves some physical violence but also and foremost psychological violence. The problem with journalism’s language is that, if one looks at the evidence and documents regarding Manus prison, the prison is legal and the detainees seem well treated.9 Nevertheless, the reality is different. “They must queue for hours for the simplest necessities, such as food, soap, water and access to a toilet; communication with the outside world is restricted and at times banned with mobile phones confiscated; translators are rarely available for those without knowledge of the English language; and access to healthcare is difficult—even for those with life-threatening conditions.” 10 The system of domination is maintained through the manipulation of stereotypical images. Australian officers are managing the prison but the main workers are the local inhabitants of Manus island. The Kyriarchal system creates fear: Australian officials informed the refugees before their arrival that the Manusians are primitive cannibals and in the same way they introduce the refugees to the Manusians as dangerous terrorists.11 Each group fears the other in order for the system to rule and to maintain itself. Dividing is also one of the main goals of the constant queuing for food, telephone and medicine. This process creates rivalry, tensions and divisions between groups. This domination is also reinforced by ongoing surveillance of the detainees. They are constantly observed by guards and CCTV.12

If the rationality of journalism cannot transcribe his experience and suffering, Boochani explores new languages to write and fight the prison which aims at reducing people to numbers, erasing their histories, identities. Finding a new language also aims at fighting the commodification and objectification of refugees’ pain and suffering in journalism, documentary photography and movies.13 Boochani strongly believes in the power of words. His main example is the term “offshore processing centre.” It is created and used by Australian officials to describe the prison to undermine what is happening inside. The term is often reiterated by media and organisations such as humanitarian ones. By calling it a prison, Boochani shifts the perspective and bring light into the reality of these places.14

It is important to consider No Friend but the Mountains and Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time as creative works of art. Through this creative process, Boochani is able to assert his identity and agency and therefore resist the system. In the book, he introduces other ways to resist the Kyriarchal system with Maysam the Whore. He does not break any rules but he is playing with them by performing, dancing and singing. This person goes beyond what the system has imagined.15 In the same way, Boochani goes beyond what the system has expected from the detainees by writing on his mobile phone. Boochani describes his role as a writer as follows:

“When I arrived in Manus, I created another image for myself. I imagined a novelist in a remote prison. Sometimes I would work half-naked beside the prison fences and imagine a novelist locked up right there, in that place. This image was awe-inspiring. For years I maintained this image in my mind. Even while I was forced to wait in long queues to get food, or while enduring other humiliating moments.”16

This is particularly visible when he describes the Green Zone, a sector of the prison from the roof of a building.

“But I write my reflections as though I were an observer, an observer with a view from above, enabling me to cut through my experiences like a knife, cut through with aggression, with tongue like a sword, cutting deep within oneself, cutting deep within, like those moments after waking from a nightmare, a nightmare depicting an arid and freezing night, a nightmare depicting life itself.”17

The narrative in No Friend but the Mountains confuses the reader. Boochani mixes the genres. He gives nicknames to all the persons depicted to protect their identity but it also transforms them into characters. The name often emphasises elements of their personality or physical features.18 By doing so, certain parts of the book can be read as fictional stories with often humour. But the reality always comes back and hit the reader. Certain parts of the book tend towards a more rational description and analysis of the situation. Moreover, the book is built around poems. If Boochani mixes genres, he also plays with multiple references to Kurdish and Iranian cultures and literature but also to Western literature or philosophy.19 This is another important part of Boochani’s work: they are meant for a Western audience. The creative approach enables him to confuse the reader to make him think and act on the situation. A similar confusion can be seen in the movie between what we hear and what we see. Images and sounds seem disconnected. By doing so, the viewer cannot watch and listen passively; he has to hear Boochani and his fellow detainees’ testimonies.20

“I am really sorry, sorry that I make you uncomfortable, but I think that I don’t have a choice other than to make you uncomfortable because this is my story.”21

Enzo Hamel

Cover picture: Screen capture of the movie Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time depicting the continuous fumigation of Manus Prison © Boochani & Sarvestani 2017

1 BOOCHANI, 2019a.

2 ROYO-GRASA 2021, pp. 1-2 & TAZREITER, 2020, p. 197

3 TAZREITER, 2020, p. 197.

4 TAZREITER, 2020, pp. 201-202.

5 TAZREITER, 2020, p. 202.

6 BOOCHANI, 2018a, pp. 91-92.

7 BOOCHANI, 2018a, pp. 93-97.

8 BOOCHANI, 2018a, p. 124.

9 BHATIA & BRUCE-JONES, 2021, pp. 83-84.

10 TAZREITER, 2020, p. 200.

11 GALBRAITH, 2019, p. 195.

12 ROYO-GRASA, 2021, p. 4.

13 BOOCHANI, 2019a.

14 BOOCHANI, 2018a, pp. xxvii-xxviii.

15 BHATIA & BRUCE-JONES, 2021, p. 85.

16 BOOCHANI, 2019b.

17 BOOCHANI, 2018a, pp. 263-264.

18 BOOCHANI, 2018a, p. xxvii.

19 BOOCHANI, 2018a, p. xxiii.

20 GALBRAITH, 2019, p. 194.

21 BOOCHANI, 2019a.

Bibliography:

- BHATIA, M. & E. BRUCE-JONES. 2021. “Time, torture and Manus Island: an interview with Behrouz Boochani and Omid Tofighian”. Race & Class, Vol. 62, no. 3 pp. 77-87.

- BOOCHANI, B. 2017. “I write from Manus Island as a duty to history”. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/dec/06/i-write-from-manus-island-as-a-duty-to-history

- BOOCHANI, B. 2018a. No Friend but the Mountains. Londres: Picador.

- BOOCHANI, B. 2018b. A letter from Manus Island. Adamstown: Borderstream Books.

- BOOCHANI, B. 2018c. “Manus prison poetics/our voice: revisiting ‘A Letter From Manus Island’, a reply to Anne Surma”. Continuum, Vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 527-531.

- BOOCHANI, B. 2019a. Writing is an act of resistance | Behrouz Boochani | TEDxSydney. LIEN

- BOOCHANI, B. 2019b. “Behrouz Boochani’s literary prize acceptance speech – full transcript”. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/01/behrouz-boochani-on-literary-prize-words-still-have-the-power-to-challenge-inhumane-systems

- BOOCHANI, B & A. K. SARVESTANI. 2017. Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time.

- GALBRAITH, J. 2019. “A Reflection on Chauka, Tell Us the Time”. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 18, pp. 193-198.

- ROYO-GRASA, P. 2021. “Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend but the Mountains: A Call for Dignity and Justice”. The European Legacy, online article, last access on October 5, at https://doi.org/10.1080/10848770.2021.1958518

- SARVESTANI, A. K. 2020. “On the Path to Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time”. PARSE, Vol. 10, online article, last access on October 5 at https://parsejournal.com/article/on-the-path-to-chauka-please-tell-us-the-time/

- TAZREITER, C. 2020. “The Emotional Confluence of Borders, Refugees and Visual Culture: The Case of Behrouz Boochani, Held in Australia’s Offshore Detention Regime”. Critical Criminology, no. 28, pp. 193-207.