*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

A shopping bag. A handbag. A school bag. A mobile phone pouch. A fashionable accessory. A baby's cot. A valuable gift. A travel souvenir. An identity marker. An electoral propaganda support. A dance accessory.

In New Guinea, there is one type of object that can perform all these functions: the bilum.

Bilum is a Tok Pisin - the island's 'creole' – word and is found in both West Papua and Papua New Guinea. It can be translated as 'string bag'1 and is sometimes referred to as a 'net bag' in the scientific literature.2 The word refers both to the finished object and to the looping technique that is characteristic of these bags.3 Depending on the type of looping, the meshes can stretch more or less and thus fit the contents. Bilum bags come in different shapes, depending on the use and the user. There are also strong regional differences between cultures, so there is no 'standard' bilum shape.4 However, women's bags are generally larger than men's, as they are more suitable for domestic activities.

Despite its appearance and name, the manufacturing technique of a bilum does not correspond to that of a net bag such as one can find in Europe. This is because the latter have meshes that are knotted together, whereas in the case of the bilum, the meshes are made up of interlocking loops. In New Guinea, the two techniques co-exist and net-type meshes are used in particular for making fishing nets.5

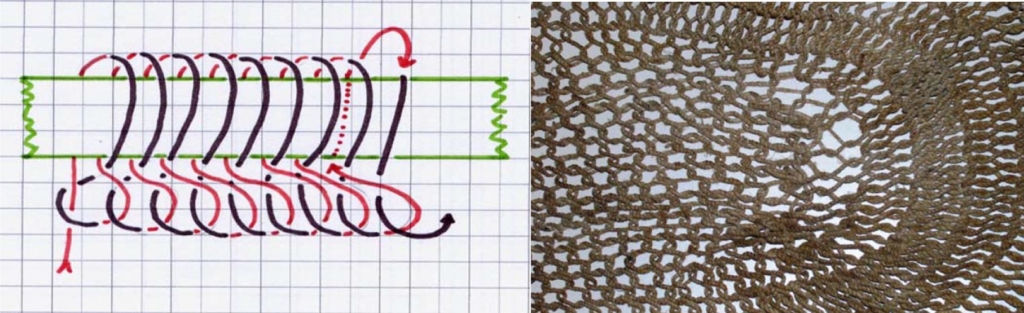

Diagram of the construction of a loop row and the type "eight figure" with a gauge and detail of a bilum with this type of loop in BOLTON, J., FYFE, A., 2009, p. 10, p. 8.

To make a bilum, it starts with the harvesting of the inner bark of certain tree species. These differ according to the geographical area but can include, for example, species from the hibiscus family.6 It is also possible to extract fibres from certain plants of the agave genus. These plants can be specially planted for this purpose. This raw material is treated with different processes depending on the region; "smoked", immersed in water, beaten.7 The extracted and cleaned fibres are then dried before they can be taken to the next stage of transformation. They are twisted and then rolled with the flat of the hand on the upper thigh to obtain threads. They will then be twisted and rolled together again to form stronger, two-stranded threads. This step is similar to textile spinning. The length required to make a domestic bilum has been estimated at 435-450 metres by Maureen A. Mackenzie in a study of the bilum from the Telefol region (Sandaun Province), which represents 44 hours of work.8 Depending on the region, these yarns are then dyed with dyes of natural origin (roucou, curcuma...) or left as is.9

Carrying net, East Sepik Region, late 20th century, dyed plant fibres, Philippe Peltier Mission © Musée du Quai Branly

The introduction of new materials since the 1930s has diversified the type of yarn used. Now, acrylic wool and nylon yarns are also used to make bilum.10 They have the advantage of requiring less work to prepare the fibre for bag making and come in a multitude of shimmering colours. However, they are usually doubled (two threads are rolled together using the same technique as for natural fibres) to obtain stronger threads of a standard size.11

These threads are then knotted using different techniques depending on the region, the type of bag and the different parts of the bag. The tools used to make the loops are limited in number: straight or more recently crochet needles, gauges to separate the rows of loops during the making of the bag, essential elements to succeed in keeping a good regularity of size. 12 The body, and in particular the fingers of the person looping the yarn, are also essential instruments not to be forgotten.13 This 5-minute video very effectively presents the different stages of making a string bag from natural fibres. The comments are from Florence Jaukae Kamel, who is the director of Jaukae Bilum Products, the creator of a bilum production cooperative based in Goroka (Eastern Highlands Province) but above all an artist known for having developed "bilumwear", clothing pieces made with the same technique as for bags.

From this basic framework, there is a wide variety of techniques to create different bag shapes, different types of loops, but above all an infinite number of colourful patterns. On some bilum, other elements are added: bird feathers, shells, nuts, seeds, ...14

Man bilum, Telefolmin, circa 1963, vegetable fibres and feathers, British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum

The equipment and technique required to make a bilum may seem simple, but it is not the easiest way to produce fabric (in the broadest sense of the word).15 Indeed, making such objects is time-consuming and involves a large technical repertoire. For example, MacKenzie estimates the total time to make a bilum from harvesting the fibres to the finished product at 163 hours (compared to 100 hours when the yarns are purchased directly). Making bilum is an almost exclusively female practice.16 Technical knowledge of their manufacture is fairly widespread and is not the preserve of a few specialists. The simple looping techniques are part of a shared cultural repertoire, the teaching of which is easily accessible.17 However, some women will distinguish themselves by their dexterity or creativity (especially in terms of patterns). The production is carried out in parallel with all the other work for which the women are responsible for a few hours a day. Thus split up, the making of a bilum can take between 6 to 8 weeks.18 If we add the economic investment that the purchase of synthetic yarns represents for them, we can understand why the bilum is a precious object. In Papua New Guinea, it is sold for between 40 and 120 Kina in the markets (i.e. between 5 and 30 euros).19 Women make string bags to sell in order to earn money and ensure their economic independence. 20 They also make them to give as gifts in their family and friend circle, during more or less formal exchanges. By giving the bilum as a gift, a woman transforms her work and creativity into a network of social relationships she can rely on.21

While worn by all in New Guinea, bilum remain associated with the idea of women and their labour, which they represent metonymically.22 They are also iconically related to the pregnant womb through their expansive capacity. These ideas of fertility and female reproductive capacity are also reflected linguistically, with the word 'bilum' in Tok Pisin also referring to a marsupial pouch or human placenta.23 The words for bilum in the different languages of the island do not all carry the same conceptual connections. For example, among thewosera-speaking Abelam, bilum is translated as wut, which refers to string bags, the womb, but also to parts of the men's house, which is considered a 'social substitute for the womb' in its ability to transform boys into initiated men.24 In the Eastern Highlands Province, bilum are more closely associated with the transport of surplus food and the protection of the young. The "big men" and "big women" are respectively called in the tairora languauge, nona tua’ora and nona tua naase (big bilum men and big bilum women), which shows their ability to protect people in the same way as a baby in its mother's bilum and their ability to maintain alliances through the exchange of surplus food. It is the protective aspects of the woman and her horticultural abilities that are emphasised through the string bags.25

There are therefore nuances in the way certain aspects of femininity and bilum are related across the island. However, the general idea of the association between women and the bilum remains and is used at a national level by the state of Papua New Guinea to make it a contemporary symbol of Papuan womanhood. The bilum allows Papua women to link together the different cultures that make up the country to participate in the creation of a national identity.26

Woman wearing a large domestic bilum.

Source: http://www.gudmundurfridrikssonblog.com/mount-hagen-markets-festivals-and-more/

At an individual level, the bilum contributes to the gender and social identity of individuals. The large open-mesh bilum worn on the forehead have a feminine connotation as their expansive capacity is more suited to the type of work that falls within women's remit such as gardening and carrying children. They also suggest an 'ancient' and more 'traditional' rural way of life for urban populations. The bilum with tight mesh (which hides the contents of the bag) have a more masculine connotation, as they were useful for carrying amulets or other precious objects without them being visible. In urban settings, this distinction tends to fade and women can be seen carrying rectangular string bags with tight loops on the shoulder. Indeed, bilum with tight loops are more suited to this lifestyle. The bilum are worn on the shoulder or around the neck so as to protect oneself from pickpockets, they are smaller in size as they are used to carry one's mobile phone, money, bible, cigarettes, ...27 Anderson suggests that the rise of smaller bags may also be related to the needs of young women in urban areas. Indeed, since they often have a wider social circle than in rural areas, they need to be able to make them more quickly so that they can give more of them away.28

Florence Jaukae Kamel (Jaukae Bilum Products), Gilda Lasibori (Bilum Export promotion association), Barbara Pagasa (bilum creator) source: https://pcf.org.nz/news/2018-04-06/bilum-bags-a-hit-at-pasifika

This type of tightly looped string bag is also more conducive to intricate colourful patterns, which are a primary element of the bilum. Indeed, the beauty of the pattern is an important criterion for the wearer of the bag. These patterns can be divided into three categories: traditional patterns (which are culture-specific, and cannot be copied if one does not own the right to do so), modern patterns (which are more or less free of rights, their precise origin is not known) and new patterns. 29 The popularity of these categories of designs depends on the region, some remain more attached to traditional designs while others value inventiveness. Women are then constantly on the lookout for new and remarkable patterns. Bilum designers having the ability to reproduce a pattern after glancing at it just once, the most popular patterns can spread rather quickly. 30 The names of modern patterns are derived from contemporary culture ("soccer ball", "noodles", "chrismas tree"...) but the patterns themselves are generally abstract and lurid. Bags with brand or flag motifs are popular. The choice of patterns and thread colours is subject to real fashion effects, although certain colours, such as those found on the flag of Papua New Guinea (red, yellow, black), remain very popular.

Having a beautiful bilum is important for one's social prestige. First of all, it must be clean. Parents make sure that schoolchildren's bags are always very clean, and the same applies to young men and women in particular and to the rest of society in general. However, the imperative is less strong for the older generations.Wearing a dirty bilum exposes one to remarks from relatives or colleagues and compromises the reputation of not only the wearer, but also those close to him or her. In the city, if one is carrying a bag characteristic of the region from which one comes from, one should wear it in a way that highlights one's region of origin. String bags are usually washed by hand, as washing machines are known to damage them.31 In addition to the need for cleanliness, the bag should also look "new", i.e. not faded or deformed. In order to meet these criteria, new bilum often have to be acquired. According to Garnier, this consumption can be estimated at around one bag per year for someone of average age.32 This demand explains why the bilum creation sector is very dynamic in New Guinea and how it can be subject to fashion effects.

Ái Vuong, ceremony bilum at the Goroka show, 2018 © The Asia Foundation

If young people are particularly concerned with these imperatives of cleanliness and novelty, it is because bilum are means of seduction. Owning a bag with beautiful, flashy designs is a good method of drawing attention to oneself and engaging in conversation. In the city, this applies to both men and women. Once married, string bags are then used to display the prosperity of the new home and the social status of the individuals. When one becomes older, carrying a bag as attractive as the young ones would be a bit inappropriate. Social networks are currently a way of posting oneself with this or that bag depending on the image of oneself one wants to give. 33 It is also interesting to point out that different bilum are used depending on the event and that there are "everyday" bags as well as "party" bags.34

In New Guinea, bilum are ubiquitous and indispensable objects in everyday life. They are characteristic "traditional" bags that still resist competition from other imported products and whose technique is perpetuated among new generations of women, whether from rural or urban backgrounds. The presence of these bags, even in the city, confirms the persistence of old practices within the evolution of Papuan society. More importantly, global trade, in the form of coloured acrylic yarns in this case, has allowed the production of string bags to flourish in the form of an expanded iconographic repertoire and evolving forms. Unlike other types of artistic creation (such as painting), production was mainly for the domestic market.35 Only faint echoes of the great dynamism of contemporary bilum reach Europe. Indeed, the string bags are very discreet in French museums and remain unknown to the general public even though they are probably the most representative production of contemporary artistic creation in Papua New Guinea and especially of the taste of its population.

Morgane Martin

Cover picture: Alberto Ricci, modern bilum made out of synthetic fibres, private collection. Reproduced In GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch. Photomontage made by the author of the article.

1 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 8.

2 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 11.

3 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 253.

4 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 19.

5 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 11.

6 GARNIER, 2016, p.15. For more information on the names of the species used, see BOLTON, J., FYFE, A., 2009, Knots, Loops & Braids : an examination of fibre craft technique in the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea, [online] website of the Upper Sepik-Central New Guinea Project, https://www.uscngp.com/papers, p. 4.

7 BOLTON, J., FYFE, A., 2009. Knots, Loops & Braids : An Examination of Fibre Craft Technique in the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea, [online] website of the Upper Sepik-Central New Guinea Project, https://www.uscngp.com/papers, p. 4.

8 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p.77

9 BOLTON, J., FYFE, A., 2010, String bag patterns and colour dyes of the upper Sepik basin and Border Mountains, [online] website of the Upper Sepik-Central New Guinea Project, URL : https://www.uscngp.com/papers, p. 3.

10 ANDERSON, B., 2015. « Style and Self Making : String Bag Production in the Papua New Guinea Highlands ». In Anthropology Today, vol. 31, n°5, p. 17.

11 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 15.

12 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 13.

13 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 69.

14 BOLTON, J., FYFE, A., 2009. Knots, Loops & Braids : An Examination of Fibre Craft Technique in the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea, [online] website of the Upper Sepik-Central New Guinea Project, https://www.uscngp.com/papers, pp. 5-6.

15 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 69.

16 According to Garnier, there are small bags made by men but their production is a very marginal activity.

GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch,p. 19.

17 ANDERSON, B., 2015. « Style and Self Making : String Bag Production in the Papua New Guinea Highlands ». In Anthropology Today, vol. 31, n°5, p. 17.

18 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 78.

19 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 13.

20 COCHRANE, S., 2009. « Bilum Breakout : Fashion, Artworld, National Pride ». In Artlink, vol. 29, n°2, p. 63.

21 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 14.

22 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, 1986, p. 14.

23 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 253.

24 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 254.

25 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 255.

26 MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University, p. 256.

27 ANDERSON, B., 2015. « Style and Self Making : String Bag Production in the Papua New Guinea Highlands ». In Anthropology Today, vol. 31, n°5, p. 16.

28 ANDERSON, B., 2015. « Style and Self Making : String Bag Production in the Papua New Guinea Highlands ». In Anthropology Today, vol. 31, n°5, p. 20.

29 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 55.

30 ANDERSON, B., 2015. « Style and Self Making : String Bag Production in the Papua New Guinea Highlands ». In Anthropology Today, vol. 31, n°5, p. 17.

31 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 43.

32 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 47.

33 ANDERSON, B., 2015. « Style and Self Making : String Bag Production in the Papua New Guinea Highlands ». In Anthropology Today, vol. 31, n°5, p. 18.

34 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 49.

35 GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, p. 57.

Bibliography:

- ANDERSON, B., 2015. « Style and Self Making : String Bag Production in the Papua New Guinea Highlands ». In Anthropology Today, vol. 31, n°5, pp. 16-20.

- BOLTON, J., FYFE, A., 2009. Knots, Loops & Braids : An Examination of Fibre Craft Technique in the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea, [online] website of the Upper Sepik-Central New Guinea Project, https://www.uscngp.com/papers

- BOLTON, J., FYFE, A., 2010. String Bag Patterns and Colour Dyes of the Upper Sepik Basin and Border Mountains, [online] website of the Upper Sepik-Central New Guinea Project, https://www.uscngp.com/papers

- COCHRANE, S., 2009. « Bilum Breakout : Fashion, Artworld, National Pride ». In Artlink, vol. 29, n°2, pp. 62-65.

- GARNIER, N., 2016. Bilum : sacs en ficelle et sociétés en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée. Issoudun, Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch.

- MACKENZIE, M., 1986. The Bilum is the Mother of Us All : An Interpretative Analysis of the Social Value of the Telefol Looped String Bag. Master Thesis, The Australian National University.

4 Comments