In recent years, provenance research has become a central issue and has been mobilised by the museum world, research institutions and public authorities. The bill on the circulation and return of cultural property belonging to public collections, adopted by the Senate on first reading on 10 January 2022, which pays particular attention to the development of provenance research, bears witness to this trend. But what exactly is it about? This week, CASOAR deciphers provenance research in theoretical and practical terms.

Multi-faceted research on collections

The discipline emerges with the desire to question the legitimate ownership and conservation of objects acquired in colonial contexts in museums. This research is interdisciplinary, due to the plurality of meanings encompassed by the term "provenances". It can refer to the geographical provenance of objects, in order to link them to the territories and populations that created and used them. It also describes the trajectory of the objects: contexts of collection, circulation through public or private collections and modes of acquisition, exhibitions, etc. Although art market actors are equally confronted with this question of provenances, this article focuses on public collections. Provenance research about the origin of objects and their lives in collections are of course intertwined. The question of the "provenances" of objects must be thought of in a transnational and relational manner, seeking to blend Euro-North American and Oceanic points of view. This is one of the proposals defended in the report submitted by Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy to the President of the French Republic Emmanuel Macron in November 2018 on the restitution of African heritage.1 While the search for provenances is linked to the current debates on restitution, it goes far beyond that, as pointed out by Marie Cornu and Noé Wagener:

"[...] beyond this material aspect of the restitution of cultural property, and behind the issue at stake, there is something else at stake, the aspiration to write this colonial history [...]. Hence the importance of taking a closer look at the trajectories of objects, the question of provenance, the capture of heritage more broadly inscribed in other histories, social, political and economic".2

The history of provenance research applied to Oceanic collections is relatively old. This is recalled by Hélène Guiot and Magali Mélandri in the introduction to issue 152 of the Journal de la Société des Océanistes.3 This text is a comprehensive overview of the work already done and gives an idea of the research underway in French museums. The first stage consisted of a census of the Oceanic holdings in French public collections. Marie-Charlotte Laroche carried out this survey in 1945, just after the Second World War. She drew up a negative assessment of the state of Oceanic collections in France, and launched an urgent appeal to undertake an inventory of all these collections, which were poorly known and poorly preserved at the time. In particular, she expressed concern about the destruction of collections in museums affected by the bombings of the Second World War, such as those in Brest, Caen and Douai.4 Research on Oceanic collections developed over the following decades, thanks to the numerous works of Anne Lavondès from the end of the 1970s, of Sylviane Jacquemin in the 1990s, and more recently of Claude Stéfani and Hélène Guiot.

In the 1980s, this research was in response to a period of intense reflection on Oceanic collections in France and throughout the world. At the time, these collections were generally not well exhibited in museums and were poorly documented. In some museums, the modes of exhibition and discourse were old and outdated and no longer in line with the contemporary reality in Oceania. The numerous researches undertaken are also linked to a great cycle of renovation of museums and exhibition spaces undertaken from the 1990s onwards. These renovations led to new circulations of objects between public collections: the creation of the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac and the bringing together of the Oceanic collections of the former musée des arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie and the Musée de l'Homme are proof of this.

In practice: some important examples and milestones in the history of provenance research in France

To illustrate more precisely what provenance research is, let us now look at some examples of practical cases that have marked the history of provenance work in museums in France.

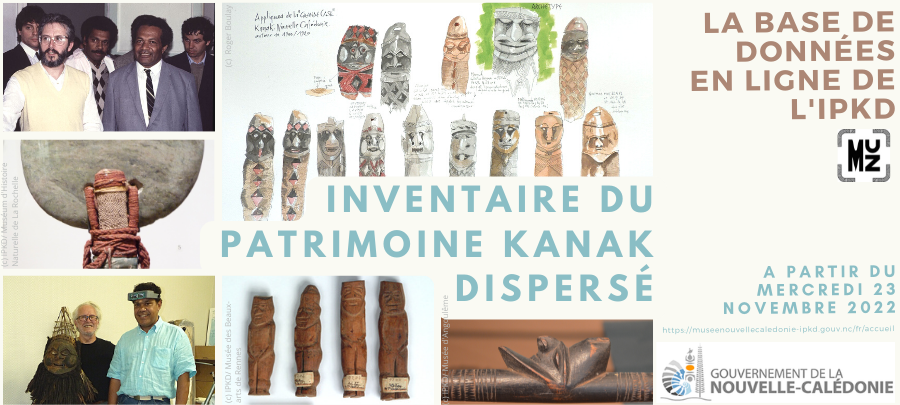

Announcement of the IPDK going live. © Musée de Nouvelle Calédonie

A major case is the inventory of dispersed Kanak heritage (IPKD). This inventory campaign began in the early 1980s at the request of Jean-Marie Tjibaou (1936-1989), a Kanak activist and politician. He commissioned the anthropologist Roger Boulay to carry out a survey of the kanak collections held in museums, first in mainland France and then in Europe. He was interested in three principal questions: Where are the objects? How are they preserved? What discourse is conveyed through them about kanak populations?5 Between 2011 and 2015, this research took on greater scope with the creation of the IPKD mission, which received financial support from the New Caledonian government. The team included Roger Boulay, Emmanuel Kasarhérou (then cultural director of the Agence de Développement de la Culture Kanak in Nouméa) and Étienne Bertrand (museographer), as well as several interns, including Marianne Tissandier (curator-restorer, responsible for the collections of the Museum of New Caledonia in Nouméa) and Jean-Romaric Néa (head of the Heritage Development Department in the Northern Province of New Caledonia). The exhibition Carnet Kanak, voyage en inventaire curated by Roger Boulay and Emmanuel Kasarhérou, at the Rochefort-sur-mer Museum of Art and History (24 February - 4 June 2022) was devoted to this work. It is currently being presented at the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac: a way of immersing oneself in research through action!6 Thus, this inventory project of the Kanak collections illustrates several issues specific to provenance research: the long-term work sometimes undertaken over several decades, the collaboration of plural and multidisciplinary teams demonstrating a broad spectrum of skills, as well as the collaborative dimension of such projects.

Mati, « Mon musée pour m’amuser », 2012, Indian ink and watercolour on paper, digital editing. © monmuseepourmamuser, https://www.instagram.com/monmuseepourmamuser/

With a view to integrating all Oceanic objects, the Ministry of Culture carried out a survey of Oceanic collections in museums in France. The mission was directed by Roger Boulay. In 2007, it was possible to estimate that there were some 65,000 Oceanic objects in 116 museums, both private and public. The Annuaire des collections publiques françaises d'objets océaniens, on the Joconde database, includes a classification of the collections by museum and indicates the most important collections in terms of number, geographical origin and the personalities who have participated in their creation.7 More localised research has been undertaken on the collections. This is the case of the Oceanic collections held in the museums of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, which were studied by the collections officers as well as Roger Boulay and Sylviane Jacquemin in the 1990s. This work was turned into an exhibition, thus making the region's collections better known and their history more visible. Entitled Oceania, Curious, Navigators and Scholars, it was held at the Natural History Museum in Lille before travelling to other museums in the region in 1997. The catalogue published on this occasion remains an important source for research.

Cover of the exhibition catalogue Oceania, curious, navigators and scholars. Lille: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1997.

Numerous research projects are currently underway. Based on the IPKD model, the government of French Polynesia is funding a comprehensive inventory of Polynesian collections scattered around the world.8 Initiated during the preparation of the exhibition Matahoata, Arts and Society in the Marquesas Islands, presented at the musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in 2016, the project is led by Hélène Guiot, Véronique Mu-Liepmann and the Musée de Tahiti et des îles-Te Fare Mahana. The database can be consulted by registration, with limited access, for museums whose collections have been inventoried. Providing funding for this research is another crucial issue. The BnF and the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac have been offering research grants for the past few years on the history and development of non-European collections. For the year 2021, Marine Vallée, curatorial assistant at the Musée de Tahiti et des Îles, post-doctoral fellow at the EATSCO EA4241 laboratory (University of French Polynesia), was the laureate with her project "Tracés de collections et d'expositions: la Polynésie française dans le paysage muséal parisien".

An important challenge for the institutions initiating the research is to make them visible and share them with a wide audience. Initially accessible only to the Museum of New Caledonia, the IPKD database is now accessible online to the public since November 2022.9 In addition, the research programme "Vestiges, indices, paradigms: places and times of African objects (14th-19th centuries)" directed by Claire Bosc-Tiessé at the French National Institute for the History of Art (INHA) includes a section devoted to mapping museums holding collections of African and Oceanic objects.10 This mapping is based on the Kimuntu directory piloted by Émilie Salaberry at the Musée d'Angoulême, which aimed to give visibility to regional collections and, above all, to put those responsible for collections of these objects – sometimes not specialised in these regions – in contact with each other.

Screenshot of the "Le Monde en Musée" database. © INHA, https://monde-en-musee.inha.fr/

The discipline of provenance research has tended to become more professional in recent years, through training (University Diploma at the University of Paris-Nanterre since January 2022, Master's seminar at the École du Louvre) and the development, by European museums or museum associations, of methodologies applied to collections from colonial contexts. The three volumes published by the German Association of Museums, for the use of museum professionals, are among the richest and most relevant for understanding such research.

Provenance research: essential in restitution processes

In May 2003, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Wellington) was officially mandated by the New Zealand government to take charge of the returns of māori and moriori ancestors.11 The Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme was established, and became an internal unit of the national museum. Between 1st July 2003 and 1st May 2017, the programme enabled the return of 420 māori and moriori human remains held in collections internationally (see here the article on the return of māori heads by France).

Restitution ceremony, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, 13th July 2018, US Embassy from New Zealand.

The process of returning Māori and Moriori human remains, as undertaken by the Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme from its inception, does not have the Te Papa Museum as its final destination. Te Papa's role is in negotiating with institutions and governments internationally and in organising the repatriation process. Upon arrival, the human remains are temporarily stored in a wāhi tapu, a repository considered sacred, within the museum. Two wāhi tapu are provided by Te Papa. The first is located within the walls of the museum, and the second is located on Tory Street in Wellington, in the collections research building. Access to the wāhi tapu is extremely limited, restricted to certain researchers, and under specific conditions regarding the handling of remains for example. However, returned human remains are not included in the museum's collections. Te Papa makes it clear that it does not claim ownership of these remains but acts as a kaitiaki (custodian) for them.12

The aim of the Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme is to enable the return of human remains for burial to the iwi, hapū or whānau concerned.13 These domestic repatriations are only carried out at a later stage, after a thorough study of the human remains, carried out by the repatriation team headed since 2007 by Te Herekiekie Haerehuka Herewini (repatriation manager) and under the expertise of an advisory committee composed of specialists in Māori culture, customs and history. Since 2003, Te Papa has reportedly returned 52 of the 420 ancestral remains returned from overseas.

Te Papa offers free access on their website to a methodological guide in provenance research, adapted and dedicated to research conducted on māori and moriori human remains. The document is addressed to museums undertaking research on their collections. The first section - 'Repatriation research: Where to start' - addresses the preparation and creation of a research protocol, the creation of a checklist, the identification of the main research questions, the creation of a database to record all the information and evidence collected, and the creation of a biographical directory of those involved (collectors, successive owners, etc.). The second section - "Repatriation research: Where to look" - details the sources that need to be exploited to carry out the research: archives, online databases, museums, universities, libraries, private collections and collectors, the network of researchers as well as the communities of origin. The third and final section addresses the final phase of the research, namely proofreading by Māori experts and communities of origin - iwi, hapū or whānau - depending on the degree of accuracy of the known provenance. Nine provenance research reports, written between 2008 and 2016, are accessible from the Te Papa website. Each report describes the human remains and any associated labels or inscriptions, and details the history of their collection and movement, as accurately as possible. This is accompanied by a survey of the area in question, with particular attention given to archaeological burial sites and the identification of the concerned iwi.

To date, the definitive restitutions of goods incorporated into French collections, which have been made from hexagonal France to Oceania, have concerned only human remains: twenty toi moko (mummified māori heads) in 2012, and the skull of Atai in 2014. The processes of these restitutions, described in previous articles here and here, have so far been localised and specific, carried out in mainland France by a limited number of individuals. The proposal for a framework law mentioned in the introduction proposes, in particular, restituability criteria for heritage human remains. The establishment of such criteria, which have yet to be discussed, would aim to surround future restitutions with generalised conditions. This is likely to be a further step in the process of increasing provenance research, which has yet to be carried out in detail for many Oceanic objects.

Marion Bertin & Soizic Le Cornec

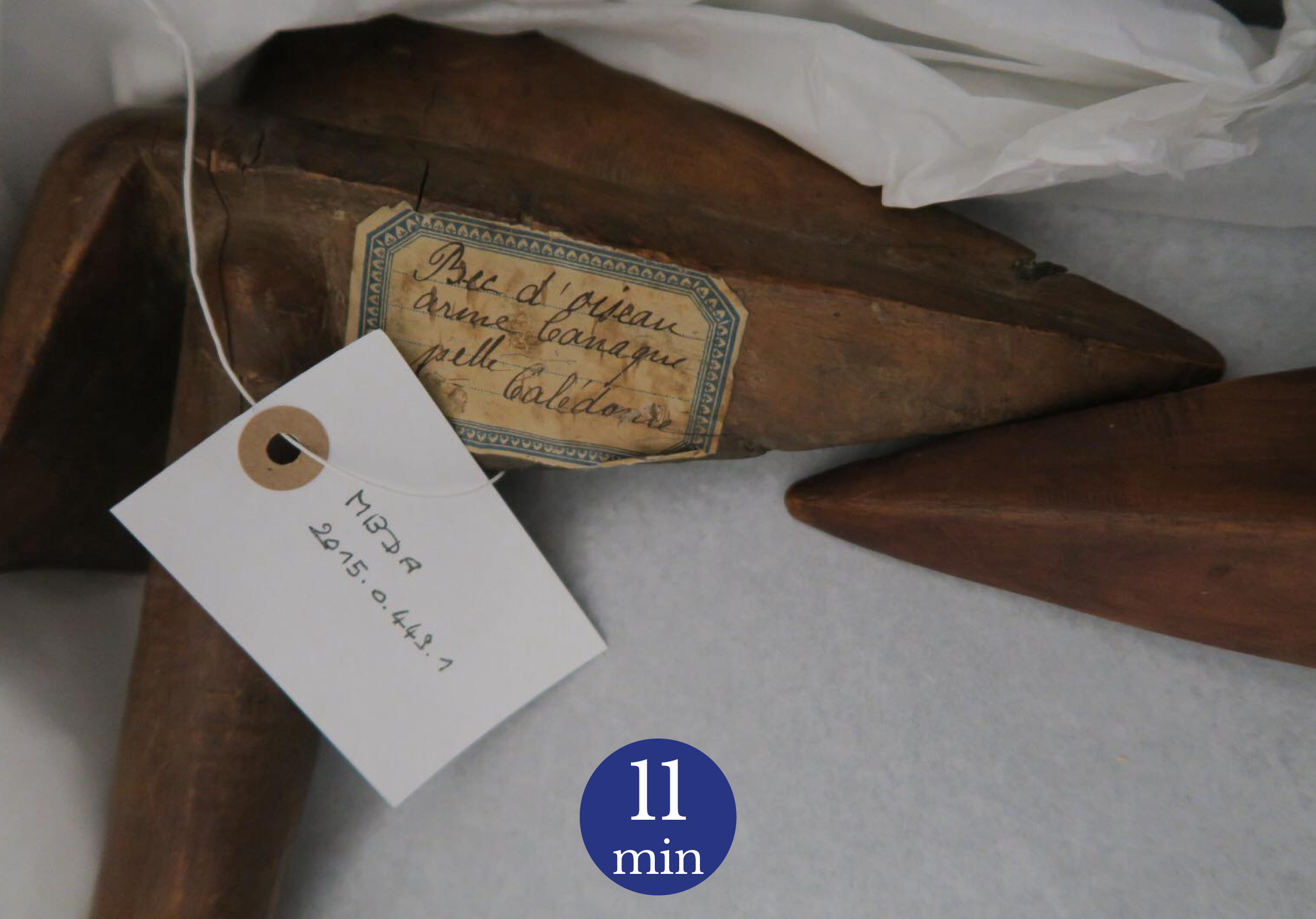

Featured image: Club, wood, L. 68 cm, New Caledonia, Le Rat donation, Musée des Beaux-Arts et de la Dentelle d'Alençon, 2015.0.449.1 © Soizic Le Cornec

1 https://www.vie-publique.fr/rapport/38563-la-restitution-du-patrimoine-culturel-africain, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

2 CORNU M., WAGENER N., 2022, « La propriété de ce qui est à tous : le débat sur la restitution des biens culturels », dans BORIES C., 2022, Les restitutions des collections muséales. Aspects politiques et juridiques, Mare & Martin.

3 MELANDRI, M., GUIOT, H., 2021. « Introduction. Pour un inventaire des collections océaniennes en France : regard rétrospectif en 2021 ». Journal de la Société des Océanistes (152), pp. 5-20. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/jso/13023 , dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

4 LAROCHE, M.-C., 1945. « Pour un inventaire des collections océaniennes en France ». Journal de la Société des Océanistes 1, pp. 51-57. URL : https://doi.org/10.3406/jso.1945.1485), dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

5 BOULAY, R., 2015. « Les collections extra-européennes en France : 25 ans après ». La Lettre de l’ocim (158), pp. 31-34.

6 https://m.quaibranly.fr/fr/expositions-evenements/au-musee/expositions/details-de-levenement/e/carnets-kanak-38717, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

7 https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Thematiques/Musees/Les-musees-en-France/Les-collections-des-musees-de-France/Decouvrir-les-collections/Annuaire-des-collections-publiques-francaises-d-objets-oceaniens , dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

8 Op. cit., MELANDRI, M., GUIOT, H., 2021

9 Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie, 2022. « Mise en ligne de l’Inventaire du Patrimoine Kanak Dispersé (IPKD) », Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie, 23 novembre 2022. URL : https://museenouvellecaledonie.gouv.nc/actualites/thematique/le-musee/mise-en-ligne-de-linventaire-du-patrimoine-kanak-disperse-ipkd, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

10 https://monde-en-musee.inha.fr/ , dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

11 The Moriori are the inhabitants of the Chatham Islands of Aotearoa New Zealand, located to the east of the two main islands.

12 SIMON. J., 2021, « Le Musée national Te Papa Tongarewa de Wellington, ou la reconnaissance d’un système administratif biculturel », dans BLIN M., NDOUR S., Musées et restitutions : Place de la Concorde et lieux de la discorde, Rouen et Le Havre, PURH, p. 173–193.

13The Māori population is structured into iwi, the largest customary social units, whose members are related to a single common ancestor, for whom the origin dates back to the time of settlement and the arrival of the first people under sail. The iwi are subdivided into hapū, themselves consisting of several whānau ('extended family').

Bibliography :

- BERTIN, M., TISSANDIER, M. (préf.), 2019. « Archives délaissées, archives retrouvées, archives explorées : les fonds calédoniens pour l’étude du patrimoine kanak dispersé ». Les Cahiers de l’École du Louvre (14). https://journals.openedition.org/cel/3737, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

- BOULAY, R., 2015. « Les collections extra-européennes en France : 25 ans après ». La Lettre de l’ocim (158), pp. 31-34.

- Carnets kanak. Voyage en inventaire de Roger Boulay, 2020. Paris, musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac.

- CORNU M., WAGENER N., 2022, « La propriété de ce qui est à tous : le débat sur la restitution des biens culturels », dans BORIES C., 2022, Les restitutions des collections muséales. Aspects politiques et juridiques, Mare & Martin.

- DEBROSSE, C., 2018. « L’Inventaire du Patrimoine Kanak Dispersé se retrouve au musée Anne de Beaujeu à Moulins ». CASOAR, 28 mars 2018. https://casoar.org/2018/03/28/linventaire-du-patrimoine-kanak-disperse-se-retrouve-au-musee-anne-de-beaujeu-a-moulins/, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

- DEUTSCHER MUSEUMS BUND, 2021. Guide relatif au traitement des biens de collections issus de contextes coloniaux. https://www.museumsbund.de/publikationen/guide-consacr-aux-collections-musales-issues-de-contextes-coloniaux/, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

- GUIOT, H., STEFANI, C., 2002. Les objets océaniens, série polynésienne, vol. 1. Chartres, musée des Beaux-Arts.

- JACQUEMIN, S., 1990-1991. « Origine des collections océaniennes dans les musées parisiens : le musée du Louvre ». Journal de la Société des Océanistes (90), pp. 47-52.

- JACQUEMIN, S., 1994. « Des objets océaniens rescapés de l’expédition d’Entrecasteaux (1791-1794) », Journal de la Société des Océanistes (99), pp. 207-208.

- LAROCHE, M.-C., 1945. « Pour un inventaire des collections océaniennes en France ». Journal de la Société des Océanistes 1, pp. 51-57.

- LAVONDES, A., 1976. « Collections polynésiennes du musée d’histoire naturelle de Cherbourg ». Journal de la Société des Océanistes 32 (51-52), pp. 185-205

- LAVONDES, A., 1990. Vitrine des objets océaniens : inventaire des collections du Muséum de Grenoble. Grenoble, Muséum d’histoire naturelle.

- LAVONDES, A., 1994. « Les collections océaniennes du muséum de Perpignan ». Annales du muséum d’histoire naturelle de Perpignan, pp. 3-12.

- Le Monde en musée, base de données. https://monde-en-musee.inha.fr/, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

- LE CORNEC, S., 2022. « De la lutte d’Ataï à la lutte pour le retour d’Ataï – Restes humains et restitutions des musées en France ». CASOAR, 11 août 2022. https://casoar.org/2022/08/11/de-la-lutte-datai-a-la-lutte-pour-le-retour-datai-restes-humains-et-restitutions-des-musees-en-france/, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

- MELANDRI, M., GUIOT, H., 2021. « Introduction. Pour un inventaire des collections océaniennes en France : regard rétrospectif en 2021 ». Journal de la Société des Océanistes (152), pp. 5-20.

- MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE, 2022. « Annuaire des collections publiques françaises d’objets océaniens », Ministère de la culture, novembre 2022. https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Thematiques/Musees/Les-musees-en-France/Les-collections-des-musees-de-France/Decouvrir-les-collections/Annuaire-des-collections-publiques-francaises-d-objets-oceaniens

- Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie, 2022. « Mise en ligne de l’Inventaire du Patrimoine Kanak Dispersé (IPKD) », Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie, 23 novembre 2022. https://museenouvellecaledonie.gouv.nc/actualites/thematique/le-musee/mise-en-ligne-de-linventaire-du-patrimoine-kanak-disperse-ipkd, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

- Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie, s.d. « L’inventaire du patrimoine kanak dispersé (IPKD) », Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie. https://museenouvellecaledonie.gouv.nc/collections/linventaire-du-patrimoine-kanak-disperse-ipkd, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

- MUSÉE DU QUAI BRANLY, 2019. « Recherches sur l’origine et l’histoire des collections du musée du quai Branly–Jacques Chirac », septembre 2019. https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Media/Medias-creation-rapide/Livret_Histoire_collections_MQB.pdf2, dernière consultation le 30 novembre 2022.

- SARR, F., SAVOY, B., 2018. Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle. Paris, Seuil.

- SIMON. J., 2021, « Le Musée national Te Papa Tongarewa de Wellington, ou la reconnaissance d’un système administratif biculturel », dans BLIN M., NDOUR S., Musées et restitutions : Place de la Concorde et lieux de la discorde. Rouen et Le Havre, PURH, pp. 173‑193.