The American nuclear bombs fell on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945. They sounded the death knell of the Second World War (1939-1945), but paved the way for the Cold War (1947-1991) whose two major protagonists were the United States (US) and the USSR. Between 1945 and 1961, both sides carried out numerous experiments with the aim of being the first to possess the most powerful atomic bomb. It was against this backdrop that, between 1946 and 1958, the United States carried out some sixty nuclear tests on several atolls in the Marshall Islands, the Micronesian archipelago that came under American rule after the Allied victory and remained so until its independence in 1986. 1

Today, CASOAR takes you back to one of the ruins of these experiments, the Runit dome, located on the atoll of Enewetak (Rālik chain, Republic of the Marshall Islands, RIM).

An update on the situation

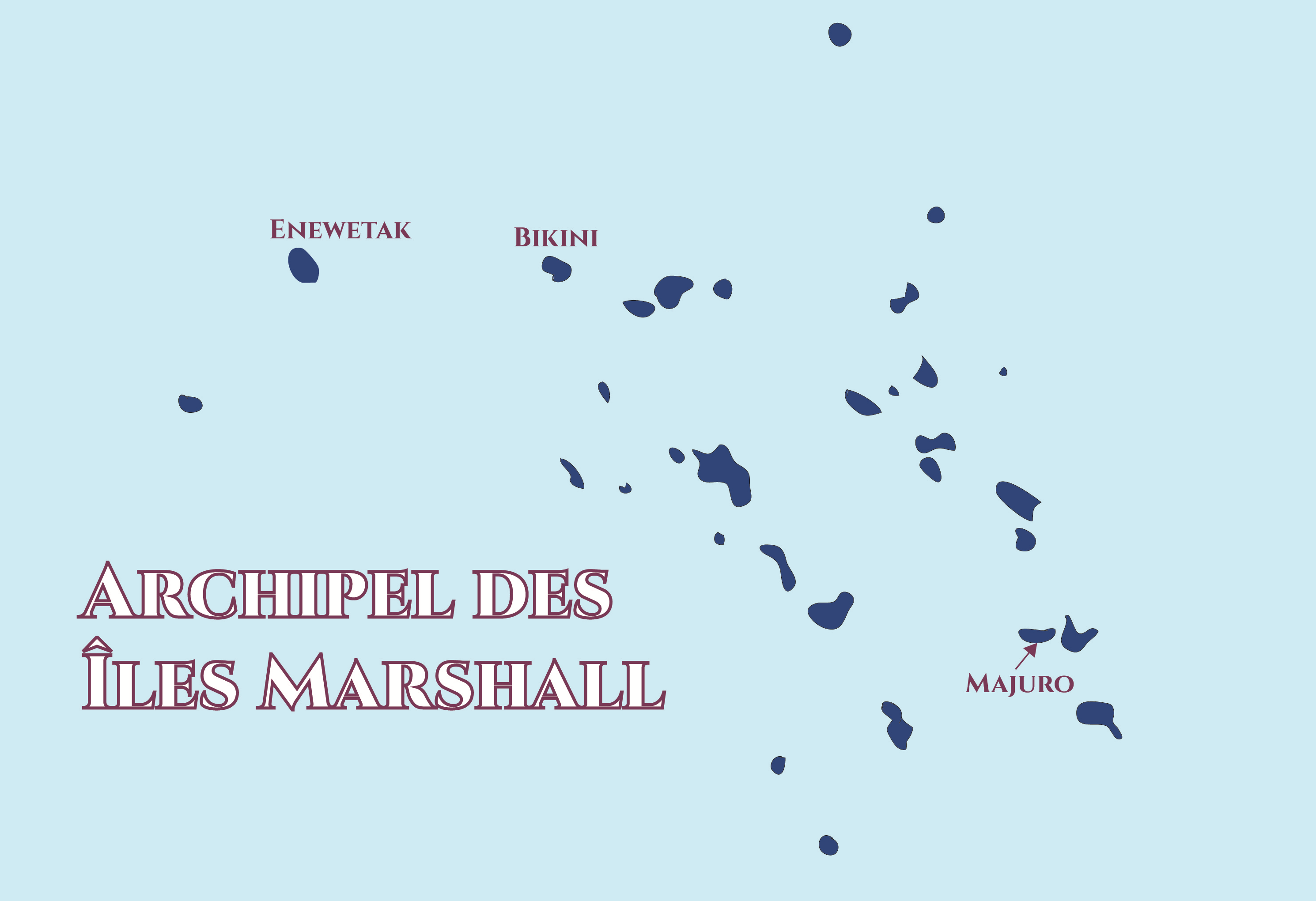

Marshall Islands map. © CASOAR

The Americans landed in a territory that had never heard of radioactivity, nuclear bombs and so on. So when the US Navy approached the chiefs of Bikini Atoll, to ask them for permission to use their land, they agreed. The Americans presented the operation in a positive light and the nuclear force as a saving power for humanity. The island's translator transposed the American speech to the inhabitants as follows: "He said that the USA wanted to use something powerful and transform it into something good and useful".2 How do you describe a phenomenon that you know nothing about, that you have never experienced? This was certainly the Americans' strength of conviction and manipulation, and it is very likely that if they had explained a little more about the ins and outs of radioactivity and nuclear bombs, the islanders would not have agreed to give up their land.

Today, history records a number of major explosions, including Castle Bravo on 1 March 1954; Ivy Mike (or Mike), the world's first thermonuclear explosion on 1 November 1952, both on Bikini; and Ivy King (or King) on 16 November 1952, this time on Enewetak atoll.

Although the US government put an end to these nuclear experiments on the atolls in 1958, it was not until 1970-1980 that their clean-up was organised.3 The top layers of soil were removed because they were impregnated with radioactive fallout. This work led to the inhalation of plutonium by Marshallese and American workers, some of whom brought their families with them. They had almost no protection and, above all, the American government did not really communicate about the risks involved.4 The waste was thrown into the sea, or in the case of Runit at Enewetak, put into plastic bags and then thrown into the Cactus Crater.5 The Cactus Crater was created by the atomic explosion on Runit on 5 May 1958.6 The waste was mixed with contaminated concrete and metal structures present on the island at the time of the explosion. Finally, as a recent study shows, nuclear waste produced by experiments carried out in Nevada (USA) was brought to the Marshalls to be buried in the crater.7 The whole thing was covered with a plug, also made of concrete: this is what is known today as the Runit dome. This covered an astronomical quantity of plutonium 239 fragments with a half-life of 24,000 years and 437 plastic bags.8

Finally, in 1980, the US government began to resettle the population of Enewetak, who now live not so far from the Dome. However, maintenance of the Dome was not guaranteed. The Americans had built the Enewetak Radiological Laboratory to monitor the architecture of the Dome and the level of radioactivity on the island.sup>9 Lastly, some of the atoll's islands have been banned because the level of radioactivity was too high. For the Americans, the sea separating them from the other islands acted as a barrier to prevent the poison from being dispersed, which is clearly entirely false.

Radiations are not visible, palpable, odorous or noisy. It is therefore an invisible presence that is surely easy to forget in everyday life. In the case of Runit, this is compounded by the policies adopted by American institutions to make the islanders forget about radioactivity. The Dome was built of concrete and presented as a barrier to the noxious gases trapped inside. However, it acts more as a tangible indicator of the presence of radioactivity in Enewetak. In fact, it seems to be the focus of concern locally and throughout the archipelago, as it cracks and radioactive vapours escape into the sea and the atmosphere, contaminating humans and non-humans alike. At Enewetak school, children learn songs about their nuclear heritage10 and Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner, a Marshallese poet, teacher, activist, etc., has written Anointed (2018), a poem focusing on the Runit dome and the disastrous legacy it contains and embodies.11 Finally, we might add that, even if radioactivity cannot be perceived by the senses, its effects are clearly visible: baby jellyfish12, skin diseases, malformations, cancers, thyroid problems, poisoning of fish and therefore of individuals. Radioactivity is therefore "what [the Marshallese live in, depriving them] of any 'elsewhere'"13 and they are well aware of this, particularly through the presence of the Dome.

But why did the United States build a concrete dome on an atoll?

The Runit Dome was built using concrete, an inexpensive material that can be poured on site, making it possible to work quickly. However, concrete is not very durable over time. It crumbles, cracks and deteriorates, as can be seen in the case of the Dome, and is exacerbated by climatic events: rising sea levels and increasingly violent and frequent typhoons. As the anthropologist Tim Ingold14 points out, an object is constrained by uses, contexts, its material(s), etc. that share its environment: the concrete of the Dome, the radioactive waste, the inhabitants of Runit, the animals and plants that occupy the Dome, the sea, the journalists, the activists, the climate (the anthropologists!) and surely many other things that don't even come to mind. So the protection that the Dome is supposed to provide is no longer really relevant. We're a long way from the architectural challenges of containing nuclear remnants and shielding them from radiation. But, as the US itself has said, "the dome has served its 'primary purpose' - to contain the waste, not be a shield against radiation".15

Aerial view of the Dome. © Screen capture This Concrete Dome Holds a Leaking Toxic Timebomb- Foreign Correspondent, publiée par ABC News (Australia).

A tale of words

L’anthropologue Holly M. Barker montre que les Marshallais ont construit leur propre langage pour parler du nucléaire et le comprendre. En effet, les insulaires considèrent qu’ils sont les seuls en droit de parler de l’expérience nucléaire et que le discours américain sur celle-ci n’est pas valable. La parole locale se tient donc contre la parole scientifique et/ou politique des États-Unis.

Plusieurs travaux qui s’intéressent à la question de l’enfouissement des déchets nucléaires mentionnent l’importance de continuer à comprendre que la force contenue sous un dôme ou une structure en béton est dangereuse16. Le danger est de percevoir ces sites d’enfouissement comme des endroits « neutres »17. Ceux-ci ne seraient plus dotés d’aucune connotation, ce qui pourrait en mener certains à les pénétrer, alors qu’ils sont hantés par des humeurs invisibles et destructrices. Face à cette menace, certains préconisent le déploiement de techniques symboliques qui permettraient de connoter les lieux souillés à un concept distinct, assimilé et compris par tous. L’utilisation d’un champ sémantique non scientifique, c’est-à-dire de termes symboliques, pour parler de ces restes, pourrait être une solution. C’est ce que fait Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner dans son poème, Anointed (2018). Elle utilise plusieurs fois le mot « tombe/tomb », de même que le mot « sépulture/grave », pour décrire l’île ; tandis qu’elle appelle le dôme de Runit « dôme fissuré/cracked dome » ou encore « coquillage en béton qui abrite la mort/concrete shell that houses death ». Elle fait donc un rapprochement entre une tombe abritant un (la) mort et le Dôme. De plus, pour elle, il ne constitue en rien une barrière contre les déchets nucléaires. La poète insiste aussi sur le fait qu’il représente une partie muette de l’Histoire de l’archipel. À travers ce poème, elle cherche des réponses à ses questions et celles des Marshallais. Elle se demande comment se souvenir d’Enewetak, comme si la puissance du nucléaire avait brouillé le lien entre les Marshallais et leur atoll. Elle demande d’ailleurs qui a accordé aux Américains le pouvoir de détruire ses îles. Finalement, la poésie est pour elle une sorte de rituel18 qui permet de faire face au problème. Elle évoque le pouvoir de guérison qu’ont les mots, mais aussi son inquiétude concernant la création d’art à partir de cette « monstruosité »19. Enfin, elle présente aussi ce poème comme un moyen pour ne pas oublier cet héritage. Pour Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner, bien que certains vivent de nouveau à Enewetak, celle-ci n’est plus une île. Elle est devenue une tombe créée par la Science du nucléaire et le Dôme en est le signe le plus concret.

Derrière son poème et les expressions qu’elle utilise, l’auteure va bien plus loin que les scientifiques qui parlent de « déchets ». Elle s’extrait du neutre qu’aurait pu produire le Dôme. C’est cet « entretien symbolique »20 qui permet aux individus, dans une certaine mesure, de se protéger contre le dôme de Runit. Cependant, cet entretien devrait aller de paire avec un entretien technique de la structure même, ce qui n’est pas le cas ici.

Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner in the video of her poem Anointed © scree capture, video Anointed, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner et Dan Lin

When you arrive on Enewetak, you can see the Runit dome, painted on the atoll's Welcome Sign. It's enough to make you want to get the hell out of there. However, the inhabitants have learnt to live with the ghosts of the nuclear testing period, as well as with its most visible ruin. The strength of the islanders therefore lies in their ability to look beyond historical events, to go beyond the memory that would lead us to think of the Dome simply as a cenotaph or memorial. This freedom enables the creation of a balance of power between the inhabitants and the Dome; the islanders and the American government; the activists and the polluters from all over the world. "Freedom/haunted: two sides [of the same experience]21 that enable the Marshallese to establish themselves on the world stage as an archipelago active in the fight against climate change. Indeed, as Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner's mother – Hilda Heine, the penultimate President of the Republic of the Marshall Islands – points out, the nuclear issue is closely linked to that of climate change.22 From this perspective, the Dome becomes one of the symbols of this new identity for the inhabitants of Enewetak and the Marshall Islands, as the foam is already licking its edges and the structure is threatened with destruction.

Enewetak's welcome sign © Screen capture This Concrete Dome Holds a Leaking Toxic Timebomb - Foreign Coresspondent published by ABC News (Australia).

Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner's work is being heard both locally and globally, thanks to her website and her presence at global events such as the Climate Conference in Paris (COP 21), Marrakech (COP 22), Bonn (COP 23) and UN.23 The nuclear legacy that she and her people carry enables the creation of new relationships and new narratives. The poem Rise: From one island to another,24 written by Marshallese poet and Inuit author Aka Niviâna, is a good illustration of these new relationships. It brings together the inhabitants of the Marshall Islands and Greenland in the face of melting ice and rising sea levels. Through poetry, they create links between the situations facing their islands and seek to mobilise all nations to fight climate change, of which they are the first victims.

The Runit dome is a ruin in the strict sense of the word. It is crumbling and therefore looks like a ruin, but it is also The Ruin par excellence of American nuclear experiments in the Marshall Islands. The Dome has become the symbol of the geological lifespan of these remains. At the same time, it symbolises the very short term nature of the dangers posed by climate change, which is causing the waters to rise. As an oxymoron, the Runit dome is the starting point and the symbol of the new construction of the Marshalls, particularly on the world stage.

Finally, the issue of burying nuclear waste is reminiscent of the problem we face in managing this type of waste in our territories. Although the Dôme is not exactly the answer to the deep burial solution that is currently the "reference solution "25, it does allow us to reflect on the situation. As we have pointed out, if the waste is to be permanently buried kilometres underground, we will still have to "remember to forget" and therefore "produce the memory of danger "26. To achieve this, projects developed by artists have been proposed. They must produce "fear and terror "27 but must not fascinate or attract. One of these projects is by musicians and actors Valentina Gaia and Rossella Ceccili. Against the backdrop of the Bure site in France, they have invented a song for children to teach them about the history of nuclear power and the risks they run if they dig up the remains. It's reminiscent of the songs learnt at school by the pupils of Enewetak... And yet, the Runit dome fascinates as much as it frightens and terrifies. Some people go there for inspiration (to write a poem), to photograph or film it (ABC News Australia and many others), to discover it and try to find its cracks.

Garance Nyssen

Cover picture: Aerial view of Runit, Enewetak, Marshall Islands. © Google Maps

1 In 1947, Micronesia became the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI), following a decision by the United Nations Security Council. The USA became the administrator. In 1986, the Marshall Islands left the dissolved TTPI and became a republic in free association with the United States, which did not make it a truly independent territory.

2 " He said the USA they want people to use something strong and turn it into something good and helpful », cette phrase est issue des documents d’archives regroupés dans le documentaire Radio Bikini in BARKER Holly M., Bravo for the Marshallese: Regaining control in a Post-Nuclear, Post-colonial World, Belmont CA, Wadsworth/Thompson, 2004, p. 80.

3 Ibid, p.37.

4 ABC NEWS (AUSTRALIA), 27 novembre 2017, « This Concrete Dome Holds a Leaking Toxic Timebomb- Foreign Correspondent ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=autMHvj3exA>, dernière consultation le 17 septembre 2018.

5 JETÑIL-KIJINER Kathy, 25 janvier 2018(a), « New year, new monsters, new poems » . Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.kathyjetnilkijiner.com/new-year-new-monsters-and-new-poems/>, dernière consultation le 26 octobre 2018.

6 In total, it seems that 9 tests were carried out on the islet of Runit, including Holly, Butternut and Magnolia.

RUST Susan, 10 novembre 2019, « How the U.S. betrayed the Marshall Islands, kindling the next nuclear disaster », LA Times. Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.latimes.com/projects/marshall-islands-nuclear-testing-sea-level-rise/>, consulté le 15 novembre 2019.

7 The study was carried out by a team of journalists from the LA Times and students from Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism. It shows that, despite the signing in 1986 of an agreement between the two countries committing the US not to withhold information from the RIM, they made no mention of the waste coming from Nevada, or of the fact that they had conducted biological weapons tests on Enewetak after the nuclear tests. According to the US government, the archives concerning the Speckled Start Test (also known as Deseret Test Center Test 68-50) are still classified. It was conducted between September and October 1968 at Enewetak.

ANONYME, s.d., « Project 112/ SHAD, Fact Sheets », Health.mil. Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Health-Readiness/Environmental-Exposures/Project-112-SHAD/Fact-Sheets>, dernière consultation le 21 août 2020.

RUST Susan, Op. cit.

8 Plutonium is used in the nuclear industry because it has a higher probability of fission/fusion than uranium 235. When we talk about half-life, we mean the time it takes for a substance to lose half its potency.

JETÑIL-KIJINER Kathy, Op. cit., 2018(a).

9 ABC NEWS (AUSTRALIA), 27 novembre 2017, « This Concrete Dome Holds a Leaking Toxic Timebomb- Foreign Correspondent ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=autMHvj3exA>, dernière consultation le 17 septembre 2018.

10 Ibid.

11 JETÑIL-KIJINER Kathy, 16 avril 2018(b), « Dome Poem Part III: ‘Anointed’ Final Poem and Video ». Disponible à l’URL: <https://www.kathyjetnilkijiner.com/dome-poem-iii-anointed-final-poem-and-video/>, dernière consultation le 23 août 2020.

12 Nickname given by the Marshallese to babies born without eyes, arms and/or legs and with transparent skin.

13 HOUDART, Sophie, « Les répertoires subtils d’un terrain contaminé », Techniques & Culture, issue 2 (n° 68), 2017, p. 88-103, p.101.

14 INGOLD Tim, Faire, Anthropologie, Archéologie, Art et Architecture, Bellevaux, Editions Dehors, 2017 [2013].

15 RUST Susan, Op. cit.

16 MOREAU, Yoann, « Être en reste face aux résidus nucléaires », Techniques & Culture, 65-66 « Réparer le monde. Excès, reste et innovation », 2016, p. 92-109 ; The Atomic Priesthood Project (APHP). Disponible à l’URL : <http://theatomicpriesthoodproject.org/>, dernière consultation le 2 octobre 2018 ; The Ray Cat Solution. Disponible à l’URL : <http://www.theraycatsolution.com/#10000>, dernière consultation le 2 octobre 2018.

17 MOREAU, Yoann, Op. cit.

18 JETÑIL-KIJINER Kathy, Op. cit., 2018(a).

19 Notre traduction : « monstrosity" , Ibid.

20 MOREAU, Yoann, Op. cit.

21 TSING, A. L., Le champignon de la fin du monde. Sur la possibilité de vivre dans les ruines du capitalisme. Paris, La découverte, 2017 [2015], p. 132.

22 DEMOCRACY NOW!, 14 novembre 2017, « First Female President of the Marshall Islands & Her Poet Daughter : We Need Climate and Nuclear Justice ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f52IZgyLL8U>, dernière consultation le 27 octobre 2018.

23 JETÑIL-KIJINER Kathy, 24 septembre 2014, « United Nations Climate Summit Opening Ceremony – A Poem to my Daughter ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.kathyjetnilkijiner.com/united-nations-climate-summit-opening-ceremony-my-poem-to-my-daughter/>, dernière consultation le 21 novembre 2018.

24 350.org, s.d., « Debout, toi l’insulaire ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://350.org/fr/debout-toi-linsulaire/#projet>, dernière consultation le 10 novembre 2018.

25 This solution requires digging several metres underground in a geologically stable environment, but future human projects around the site must also be taken into account.

POIROT-DELPECHE, S. & RAINEAU, L., « Le stockage géologique des déchets nucléaires: une capsule anti-temporelle » In Gradhiva, numéro 28, 2018, p.143- 169, p. 144.

26 Here they quote one of the principal characters of the film Into Eternityde Michael Madsen (2011) in POIROT-DELPECHE, S. & RAINEAU, L., « Le stockage géologique des déchets nucléaires: une capsule anti-temporelle » In Gradhiva, numéro 28, 2018, p.143- 169, p. 154.

27 Ibid, p.154.

Bibliography:

- ABC NEWS (AUSTRALIA), 27 novembre 2017, « This Concrete Dome Holds a Leaking Toxic Timebomb – Foreign Correspondent ». Disponble à l’URL : <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=autMHvj3exA>, dernière consultation le 17 septembre 2018.

- BARKER, Holly M., Bravo for the Marshallese : Regaining control in a Post-Nuclear, Post-colonial World. Belmont CA, Wadsworth/ Thompson, 2004.

- DEMOCRACY NOW!, 14 novembre 2017, « First Female President of the Marshall Islands & Her Poet Daughter : We Need Climate and Nuclear Justice ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f52IZgyLL8U>, dernière consultation le 27 octobre 2018.

- HOUDART, Sophie, « Les répertoires subtils d’un terrain contaminé », Techniques & Culture, issue2, n° 68, 2017, pp. 88-103.

- INGOLD Tim, Faire, Anthropologie, Archéologie, Art et Architecture. Bellevaux, Editions Dehors, 2017 [2013].

- MOREAU Yoann, « Être en reste face aux résidus nucléaires », Techniques & Culture, 65-66 « Réparer le monde. Excès, reste et innovation », 2016, pp. 92-109

- POIROT-DELPECHE, S. & RAINEAU, L., « Le stockage géologique des déchets nucléaires : une capsule anti-temporelle » In Gradhiva, 2018, numéro 28, pp. 143- 169.

- TSING, A. L., Le champignon de la fin du monde. Sur la possibilité de vivre dans les ruines du capitalisme, Paris, La découverte, 2017 [2015].

- JETÑIL-KIJINER Kathy, 24 septembre 2014, « United Nations Climate Summit Opening Ceremony – A Poem to my Daughter ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.kathyjetnilkijiner.com/united-nations-climate-summit-opening-ceremony-my-poem-to-my-daughter/>, dernière consultation le 21 novembre 2018.

- JETÑIL-KIJINER Kathy, 25 janvier 2018(a), « New year, new monsters, new poems ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://www.kathyjetnilkijiner.com/new-year-new-monsters-and-new-poems/>, dernière consultation le 26 octobre 2018.

- JETÑIL-KIJINER Kathy, 16 avril 2018(b), « Dome Poem Part III: ‘Anointed’ Final Poem and Video ». Disponible à l’URL: <https://www.kathyjetnilkijiner.com/dome-poem-iii-anointed-final-poem-and-video/>, dernière consultation le 23 août 2020.

- The Atomic Priesthood Project (APHP). Disponible à l’URL : <http://theatomicpriesthoodproject.org/>, dernière consultation le 2 octobre 2018.

- The Ray Cat Solution. Disponible à l’URL : <http://www.theraycatsolution.com/#10000>, dernière consultation le 2 octobre 2018.

- 350.org, s.d., « Debout, toi l’insulaire ». Disponible à l’URL : <https://350.org/fr/debout-toi-linsulaire/#projet>, dernière consultation le 10 novembre 2018.