*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

[Please note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this article may contain images or names of deceased persons in photographs or printed material.]

Ten Canoes (10 canoes, 150 spears and three wives) is a film about Arnhem Land and its people, made with and by them. It is a film for Indigenous people and it is also an ambassador film for Aboriginal culture and therefore also made for an audience outside this culture. It is a story of forbidden love, brotherly bonds, kidnapping, witchcraft and revenge, treated with poetry and humour. In short, this is a rich work that CASOAR really recommends!

The film is set in the centre of Arnhem Land, in the Arafura swamp region, at a time when the Yolngu people lived according to rules and traditions ("the Law1") that their ancestors had been respecting for several thousand years.2This geographical space is presented at the opening of the film through a bird's eye view of the swamp and other characteristic landscapes of the area (river and waterways), in the manner of a mythical cartography to illustrate the actions of Yurlunggur, the first ancestor and founding principle of the landscape. This approach to the territory is significant because for the Yolngu "the ancestral force takes [...] form through the landscapes, and the Men who belong to them also become the protectors of these lands".3 The images of the Arafura Swamp are accompanied by the description of a Dreaming4narrated by David Gulpilil, a famous Aboriginal actor and filmmaker5 from Ramingining. In voice-over, the narrator tells us the story of several intertwined stories.

View from the sky of the Arafura Swamp. © Vertigo, Ten Canoes, 2007.

An inclusive creation process

À l’origine de Ten canoesoriginated in 2000 when director Rolf de Heer and David Gulpilil met for the first time in a film collaboration in which the actor played the lead role (The Tracker, Rolf de Heer, 2002). Shortly after this meeting, Gulpilil invited de Heer to spend several days with his family in Ramingining. During these moments of exchange and their excursions to the Arafura swamp, David Gulpilil expressed the wish that Rolf de Heer make a film in the swamp, with his people (the Yolngu) and in the language(s) of his people.6

Map of Arnhem Land, the Arafura swamp and Ramingining. © CASOAR

In Ten Canoes all the actors (non-professionals7 except Gulpilil) are from the Arafura swamp region, the majority being from the Ganalbingu clan or related. Ten Canoes This fact was not without consequence on the casting of the film, since the complex system of kinship with moieties determining the rules of marriage and relationships among other things, prohibited some actors and actresses from playing on screen the role of husbands and wives:

“Every Yolngu is classified as being of one of two moieties: everyone is either Yirritja or Dhua. A Yirritja man cannot be married to a Yirritja woman, and hence half the women in Ramingining, being Yirritja, were immediately excluded from consideration for that role.”8

The importance of kinship: (1) Ngulmarmar; (2) Marrakaywarr; (3) Djarri; (4) Gunyirrnyirr; (5) Ngulang #2; (6) Mangan; (7) Guminydju; (8) Dhulumburrk; (9) Dhunupirri; (10) Kikirri. Dessin fait par Louise Hamby à partir d’une photo de Thomson. IN HAMBY, L., 2007. “Thomson Times and Ten Canoes (de Heer and Djigirr, 2006)”. Studies in Australasian Cinema 1 (2), p. 131

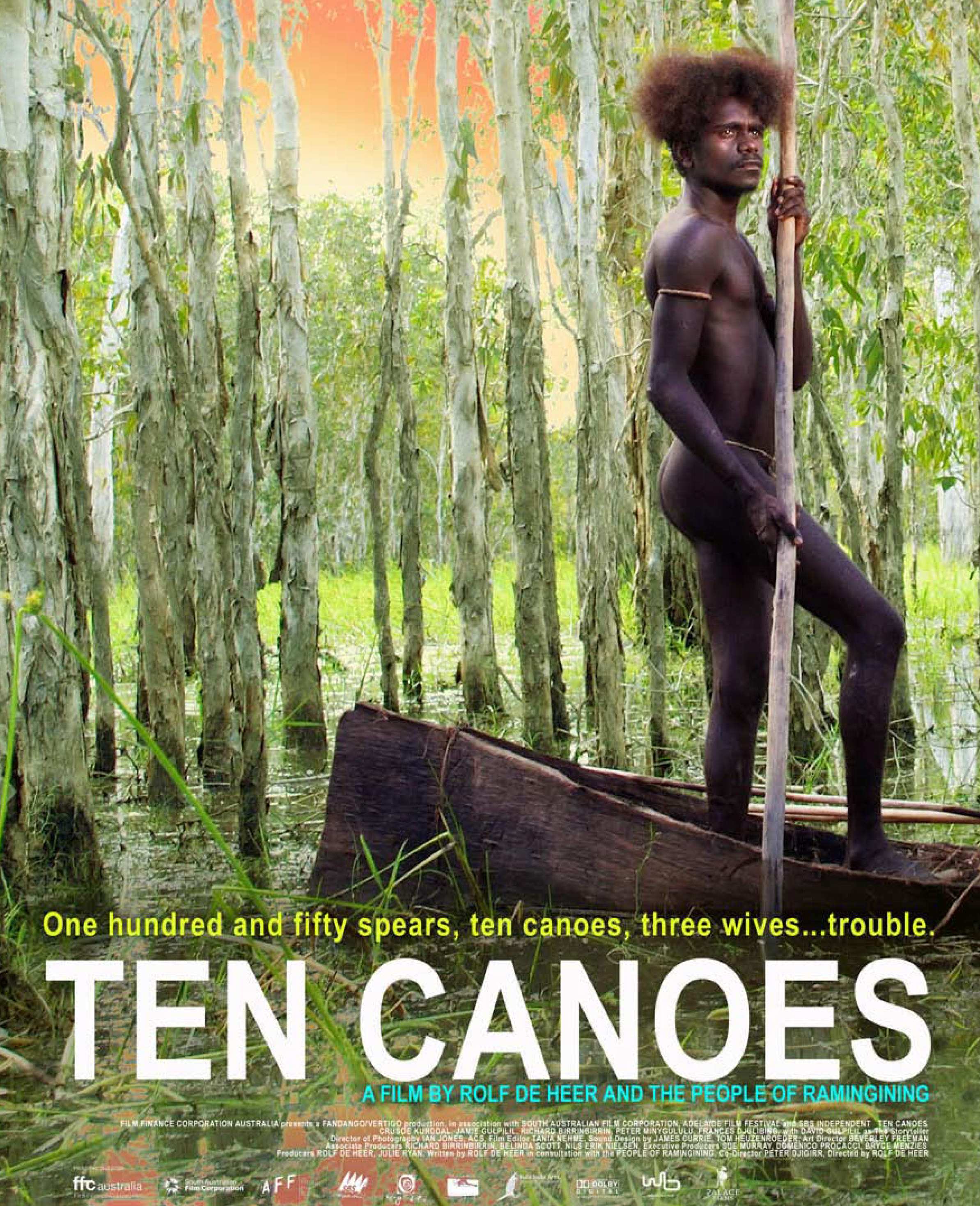

In addition to their role as actors, the people hired on the set were responsible for making the artefacts used in the film, such as the canoes, spears, thrusters and huts. As we shall see, they also played a role in the development of the script. This co-production is mentioned on the original poster of the film: "a film by Rolf de Heer and the people of Ramingining”.

Poster of the film. Ten Canoes© Vertigo

Regarding the language issue raised by Gulpilil, it was of primary importance for this project. Born in the community of Ramingining, a place with many Aboriginal languages (sixteen clans for eight language groups), Ten Canoes Ten Canoes involved speakers of different languages - and for whom English is sometimes only the fifth or sixth language, not always spoken fluently.9 A language is usually clan-specific, but this does not impede understanding between members of different clans, as most languages in the same area are well understood by all, although everyone speaks in their own language. Thus, among the film crew, while David Gulpilil speaks Mandalpingu, other actors speak Ganalbingu.10 This linguistic diversity is reflected on screen, with different Yolngu languages being used in the dialogues depending on the mother tongue of each actor. What is important here is the use of local languages, although English is also used in order to spread Yolngu culture.

“They know that all indigenous languages are under threat in this country and they want theirs to stay alive. There’s an incredible desire to show their stories to the rest of Australia.”11

Three versions of the film were produced: one with dialogue in Yolngu languages and narration and subtitles in English; one with dialogue in Yolngu languages, narration in Mangalpingu and subtitles in English; and one without subtitles only in Yolngu languages. These last two versions make Ten Canoes Ten Canoes the first feature film entirely in Aboriginal languages.

A dense and ramified story

It is a plot with a complex stratigraphy that is presented to us. The narrator takes us back in time through several stories. One of them is a wild goose egg hunt in which some of his ancestors participate. Undated, the episode is described as taking place in a distant historical time, 'in the time of [his] ancestors'.12 During the hunt, and while the men are building the canoes that will allow them to access the marsh where the geese lay their eggs, one of the warriors offers to tell his brother a story. The warrior, Miningululu, knows that his younger brother Dayindji is in love with the youngest of his wives and wishes to warn him against this prohibition by means of the legend of two other brothers: Ridjimiraril and Yeeralparil.

This legend is the second story in this film, which is presented to us in alternation with the first: in mythical times, after the Beginning and when men were already complying with the great ceremonies and the Law respected by the hunters of historical times13, the young Yeeralparil also coveted the wife of his elder brother. Their adventures (the arrival of a stranger on the territory, a strange disappearance and other adventures that we let you discover) are told by the narrator in voice-over, and played on screen by Miningululu who tells Dayindji about them. Hunting techniques, social rules ("the proper way"14), mythical stories, Dayindji "There is much for him to learn on this hunting”.15

A complex and original narrative device

The initiation myth told to Dayindji by Miningululu aims both to help the young man grow up and to transmit values to those who will hear it. The narrator says that he tells these stories in the hope that it will help the viewers in the same way that it helped Dayindji.16 Mocking the formal codes of Western storytelling, he begins his intervention with an ironic "once upon a time", which serves to introduce a situated narrative, in which the narrator addresses viewers who are strangers to his culture ("this is not your story, it's my story", "my people, my land"17"). In this way, the film has a pedagogical aim and a role in putting images into the picture ("then you can see the story and understand it"18). The film is actually aimed at two audiences from different cultures, and seeks to be enjoyable and intelligible to both:

“The Yolngu storytelling tradition is strong, but its conventions are very different to those of Western storytelling. It was soon clear that the challenge would be to create a story, to make a film, that would not only satisfy Western cinema going audience, used to Western storytelling conventions, tastes and requirements, but that would also satisfy Yolngu requirements.”19

Meeting the requirements of the Yolngu narrative tradition necessarily meant telling a story that was both substantively believable and consistent with the formal modalities of a mythic narrative - for "a good story must be told correctly".20 The result is a deliberate complexity, a story with many layers, or to use the narrator's metaphor, many branches. One can then easily find oneself navigating between five different narratives contained within each other, through phenomena of reported speech and telescoping perspectives. For example:

- the narrator in voice-over tells us about the goose egg hunt during which:

- Miningululu, while participating in the elaboration of the canoes, tells Dayindji a mythical story during which:

- Ridjimiraril, Yeeralparil and their people notice the arrival of a stranger in their territory, which leads to a discussion during which:

- everyone hypothesises about the reason for the stranger's presence in the area durin which::

- the stranger is seen to act in accordance with each character's assumptions.

The assumptions made by the characters, as well as some of the reported speeches, are present both in the protagonists' dialogue and on the screen. To put it another way, when someone talks about something, we see that something happen on film. The result is a great plurality of points of view, as if no opinion or aspect of the story should be omitted, as if “all the parts of the story have to be told for proper understanding”21 of the whole. Myth is not a monologue, it is a dialogic22 and polyphonic story.

The multiplicity of stories and levels of narration, the multiplicity of points of view translated into images is faithful to the mythical tale told by Miningululu. Quickly, like the one told to Dayindji, “the story 's growing into a large tree now, with branches everywhere”.23 In addition, the narrator addresses the audience directly. The fourth wall is very regularly broken to challenge, clarify a point or help follow the progress of the story ("the story must stop for a moment"24). There are also intriguing moments that need explaining (to the viewer and to Dayindji), which creates a discontinuity in the narrative.

All this questions our own linear relationship to time, whereas on the contrary the time of the Dreaming "is not based on a past History tending to continue in a distant future, but takes place in an active present".25 This conception of mythical time as "a world similar to ours, which evolves and acts on our present world"26 is consistent with the frequent back and forth between the adventures of Miningululu and Dayindji on the one hand and Ridjimiraril and Yeeralparil on the other. To make the superimposition of the different narrative threads more intelligible, the image is treated alternately in colour (for the mythical time when Ridjimiraril and Yeeralparil's actions took place) and in black and white (for the interludes illustrating the historical time of the collection of goose eggs by Miningululu, Dayindji and their group).

Giving life to ethnographic photographs

The choice of black and white to deal with the historical period, but also the goose egg hunt as a narrative thread and the presence of the ten canoes as a prominent feature of the film, were suggested by the actor David Gulpilil:

[…] just before I left […] David came in. And said we need ten canoes. And I said, what? And David said we need ten canoes. So what, why, do we need ten canoes for? And he said for the film. And David you know we don’t even know what the film is really going to be about. How can we need ten canoes? And he said aaagh as if I was an idiot, […] and he just walked out. […]

Half an hour later he came back with this battered plastic blue folder and opened it up and shoved the Thomson ten canoes photos in front of my face and I looked at it and went baaaagh, this is so cinematic; this so fantastic what an image. This is brilliant. So I looked at the photo and I looked up at David and said right we need ten canoes. 27

This photograph that David Gulpilil showed to Rolf de Heer was taken by Donald Thomson in the 1930s in the Arafura Swamp region where Ten Canoes was shot. Ten CanoesDonald Thomson (1901-1970) was an Australian anthropologist who worked extensively with the Yolngu people in Arnhem Land between 1935-37 and 1942-3. During his years of fieldwork, Thomson collected 5500 objects and took 2500 ethnographic photographs and 1500 natural history photographs; all of these are now part of the Museums Victoria collection in Melbourne.28 During his time in Arnhem Land, Thomson shot 22,000 feet (6700 metres) of cinefilm to make a documentary about Yolngu people, sadly all this work was destroyed in 1946 in a fire at the Commonwealth Film Unit of the Department of Information (Melbourne) where it was stored.29

Donald Thomson (1901-1970), State Library of Victoria, Australie.

While Thomson was never able to make the documentary film he wished to make to complete his research amongst Yolngu, Ten Canoes this project was given a second life with Ten Canoes. Indeed, as explained earlier, Ten Canoes Ten Canoes is based on an alternation of black and white images with images in colour. While the coloured images depict the mythical time, that of the Dreaming, the black and white moments are a depiction of “Thomson Time”.

“Thomson Time” is a way to talk about the 1930s, when Donald Thomson was in Arnhem Land and which is seen by Yolngu people as “the time when [they] practised their traditional cultural ways, unaffected by contact with outsiders”.30 To this extent, “Thomson Time” and the images in black and white in Ten Canoes Ten Canoes are meant to be depictions of an untouched Yolngu “tradition” which is cherished by Yolngu people themselves.

The film as a way to foster a cultural revival

Left: Kikirri, a Ganalbingu man, is placing the goose eggs in the canoe while Djarri, a Djinba man, stands behind. Photograph by D.F. Thomson, Museum Victoria.

Right: In the re-created scene for Ten Canoes, Jamie Gulpilil is placing the eggs and Peter Minygululu is behind. Photograph by James (Jackson) Geurts. © Fandango Australia and Vertigo Productions.

Ten Canoes Ten Canoes was built around Thomson’s pictures which provide a way to structure the film’s story. The people of Ramingining wanted the film to depict a goose egg hunting expedition, as was the case in Thomson’s photographs. While this practice was common during “Thomson time”, it had not been practiced by anybody for decades. In this matter, Ten Canoes Ten Canoes allowed for the revival of a discontinued practice. While this is a pretty uneventful practice, the goose egg hunt is used as a background setting for the story to unravel in the Arafura swamp. This location is the same as that of Thomson’s photographs and is also continued in the mythological moment of the film shot in colours. Filming in the swamp proved to be exhausting for the crew who not only had “to relearn old skills, such as polling a bark canoe through thick reeds without falling out, but they had to learn the new skills associated with screen acting” in an environment which was full of mosquitoes, crocodiles and leeches.31 The black and white scenes which were reproducing almost exactly Thomson’s images were very slow and tiresome to shoot. Their technique which was very close to that of Thomson who used a slow shutter speed for most of his photographs, so that both Thomson’s and Rolf de Heer’s aesthetics and their “careful staging” created a pictorial composition. 32

As mentioned earlier, the filming of Ten Canoes Ten Canoes was not only a way to revive goose egg hunting, but also led Yolngu people to “mak[e] all the artefacts needed for the production: the spears and stone axes; the dilly bags and canoes; the armbands and the shelters”. 33 Through this practice, it was a “feeling […] of cultural renewal, of bringing back the old times” 34 for people of Ramingining. Thomson’s photographs were consulted for the techniques used to make the bark swamp canoes, but people like Peter Minygululu and Philip Gudthaykudthay who were in their sixties and seventies had knowledge and expertise in these techniques making. Building a “Thomson canoe” was a “real pride” for everybody and a tangible proof of the revival of once “forgotten aspects of their culture”.35 While objects were the tangible elements of the revival for Ramingining people, Ten canoes as well act as well as a tangible object through which this knowledge about canoe making is kept alive thanks to the recording of the practice in the film. In Peter Djigirr’s words – co-director of Ten Canoes –, the film is a way for white people to see that culture is still alive.36 Although Ten Canoes Ten Canoes is a fiction, the film is “based on a skeleton of veracity” 37 , which make some people consider it as an ethnographic film.

In multiple aspects of the film, whether it is because of the similarity in the style of Thomson’s and de Heer’s images, the use of cultural artefacts, or the revival of “cultural traditions”, we can talk of a cultural continuity and fluidity of the different time periods evoked in the film. Furthermore, Ten Canoes Ten Canoes is not an isolated project: another eight Canoe projects now exist. Each one of these projects is based on the Ramingining community. For example, “Eleven Canoes”, which started before Ten Canoes Ten Canoesaimed at teaching teenagers how “to make documentary films about the renewal of cultural practices resulting from the making of the film”.38 « Fourteen Canoes » est un livre qui « contient de nombreuses photos en noir et blanc de Donald Thomson qui sont au cœur du film ainsi que des images en couleur recréées par James (Jackson) Geurts ». 39 Finally, when visiting Twelve Canoes's website, we can see that the project will be updated in 2021. Ten Canoes Ten Canoes and the photographs of Donald Thomson are far from having told the whole story of the people of Ramingining who are at the core of all these projects.

Margot Duband & Clémentine Débrosse

Image à la une : Jamie Gulpilil in Ten Canoes © Vertigo Productions

1 « The Law »

2 TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p.2.

3 GRAINDORGE, C., 2018. « En finir avec nature et culture ? L’exemple de la peinture en Terre d’Arnhem. CASOAR : https://casoar.org/2018/05/23/en-finir-avec-nature-et-culture-lexemple-de-la-peinture-en-terre-darnhem/

4/ Notion complexe traduite généralement en français par « Temps du rêve », et qui constitue un temps à la fois révolu et continuant d’évoluer parallèlement au nôtre et d’agir sur notre monde. Voir à ce sujet nos précédents articles :

– GRAINDORGE, C., 2018. « En finir avec nature et culture ? L’exemple de la peinture en Terre d’Arnhem. CASOAR : https://casoar.org/2018/05/23/en-finir-avec-nature-et-culture-lexemple-de-la-peinture-en-terre-darnhem/

– NYSSEN, G., 2018. « À l’origine : le Rêve – Les peintures corporelles en Australie ». CASOAR : https://casoar.org/2018/01/03/a-lorigine-le-reve-les-peintures-corporelles-en-australie/

5 Crocodile Dundee (1986), Australia (2008), etc.

6 TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p.9.

7 S’ils ne sont pas professionnels du cinéma, de nombreux acteurs du film occupent une place importante dans la vie culturelle de Ramingining, en tant que peintres, danseurs, membre de la coopérative Bula’Bila Arts Aboriginal Corporation (https://bulabula.com.au/about/) ou « ceremonial leader ».

8 “Every Yolngu is classified as being of one of two moieties: everyone is either Yirritja or Dhua. A Yirritja man cannot be married to a Yirritja woman, and hence half the women in Ramingining, being Yirritja, were immediately excluded from consideration for that role.” TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p.12.

9 TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p.11

10 TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM,, p.11

11 “They know that all indigenous languages are under threat in this country and they want theirs to stay alive. There’s an incredible desire to show their stories to the rest of Australia.” TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p.11

12 Film “The time of my ancestors”, 4’27’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

13 Film, 12’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

14 Film “The proper way”, 9’40’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

15 Film “There is much for him to learn on this hunting”, 8’10’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

16 Film, 9’40’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

17 Film « It’s not your story, it’s my story », “my people, my land”, 1’28’’ et 1’45’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

18 Film “Then you can see the story and know it”, 1‘49‘‘ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

19 “The Yolngu storytelling tradition is strong, but its conventions are very different to those of Western storytelling. It was soon clear that the challenge would be to create a story, to make a film, that would not only satisfy Western cinemagoing audience, used to Western storytelling conventions, tastes and requirements, but that would also satisfy Yolngu requirements.” TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p.10.

20 Film, “A good story must have proper telling », 59’40’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

21 Film “All the parts of the story have to be told for proper understanding”, 55’45’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

22 Théorisé par le philosophe et théoricien de la littérature Mikhail Bakhtine, le dialogisme est l’interaction entre le discours du narrateur principal (ici David Gulpilil) et les discours des autres personnages. Cette polyphonie narrative permet la représentation de points de vue variés, conférant à l’ensemble une certaine neutralité, sans pour autant masquer les opinions divergentes derrière un monologue dominé par le narrateur principal. Mikhaïl M. Bakhtine, Esthétique et théorie du roman, Paris, Gallimard, 1978, 488 p.

23 Film, “the story ‘s growing into a large tree now, with branches everywhere” puis 55’41’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

24 Film, “the storytelling must stop for a while », 13’23’’ – VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

25 GRAINDORGE, C., 2018. « En finir avec nature et culture ? L’exemple de la peinture en Terre d’Arnhem. CASOAR : https://casoar.org/2018/05/23/en-finir-avec-nature-et-culture-lexemple-de-la-peinture-en-terre-darnhem/

26 Ibid.

27 DE HEER, R., 2006, interview about the role of Donald Thomson with L. Hamby and L. Allen, Adelaide, 16 March.

28 HAMBY, L., 2007. “Thomson Times and Ten Canoes (de Heer and Djigirr, 2006)”. Studies in Australasian Cinema 1 (2), p. 127.

29 RUTHERFORD, A., 2012. “Ten Canoes and the Ethnographic Photographs of Donald Thomson: ‘Animate Thought’ and ‘the Light of the World”. Cultural Studies Review 18, p. 128.

30 TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p. 7.

31 TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p. 13.

32 RUTHERFORD, A., 2012. “Ten Canoes and the Ethnographic Photographs of Donald Thomson: ‘Animate Thought’ and ‘the Light of the World”. Cultural Studies Review 18, p. 111.

33 TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM, p. 12.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 VERTIGO, 2007. Interview of Peter Djigiir. Ten Canoes.

37 HAMBY, L., 2007. “Thomson Times and Ten Canoes (de Heer and Djigirr, 2006)”. Studies in Australasian Cinema 1 (2), p. 145.

38 Ibid, p. 135.

39 Ibid, p. 136.

Bibliography:

- DE HEER, R., 2006, interview about the role of Donald Thomson with L. Hamby and L. Allen, Adelaide, 16 March.

- GRAINDORGE, C., 2018. « En finir avec nature et culture ? L’exemple de la peinture en Terre d’Arnhem. CASOAR : https://casoar.org/2018/05/23/en-finir-avec-nature-et-culture-lexemple-de-la-peinture-en-terre-darnhem/

- HAMBY, L., 2007. “Thomson Times and Ten Canoes (de Heer and Djigirr, 2006)”. Studies in Australasian Cinema 1 (2), pp. 127-146.

- NYSSEN, G., 2018. « À l’origine : le Rêve – Les peintures corporelles en Australie ». CASOAR : https://casoar.org/2018/01/03/a-lorigine-le-reve-les-peintures-corporelles-en-australie/

- RUTHERFORD, A., 2012. “Ten Canoes and the Ethnographic Photographs of Donald Thomson: ‘Animate Thought’ and ‘the Light of the World”. Cultural Studies Review 18, pp. 107-137.

- TUDBALL, L., and LEWIS, R., 2006. Ten Canoes: A Study Guide. ATOM.

- VERTIGO, 2007. Ten Canoes.

1 Comment so far