*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

“It is high time that the people of this country held their heads high… and have pride in their country. If not now, when ?”1

On February 26, 2021, Michael Somare, one of the most important Pacific personalities of the 20th century passed away in Port Moresby after a long illness. Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea for seventeen years and four different terms, he was considered the father of the Papuan nation and architect of the country's independence.

The casket of Sir Michael Somare was carried into the East Sepik Provincial Assembly on Monday, the day before his burial in Wewak © https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/438562/png-s-founding-father-laid-to-rest

In 1936, when Michael was born on the island of New Britain, Papua New Guinea was a colony under Australian mandate. When he died forty-five years later, the country was independent and had a voice of its own in the Pacific. These radical changes are due in part to the political intelligence of this man who was able to bring people together and build a nation, despite the many obstacles on the way to independence.

Let's go back in time. In 1919, the Treaty of Versailles forced Germany to give up all of its colonies, including the northeast of New Guinea. It then came under the control of Australia, which already owned the south of the island. Following the Second World War, the United Nations confirmed Australia's mandate over the region, with clear objectives: Australia must prepare Papua New Guinea for independence and work for the economic, social and physical development of the local population.2 But in reality, despite the large sums of money injected into the education and health of Papuans, economic investments favoured private Australian companies. At the beginning of the 1960s, when it was decided to create a legislative assembly made up of a majority of Papuans, it was clear that it was going to be a challenging task to find Papuan politicians who spoke English and had received the necessary education to hold state office. Michael Somare, who took a seat in the legislature in 1968, became the symbol of a new generation of Papuans who were now willing to take on an important political role and were able to discuss with the Australian government.

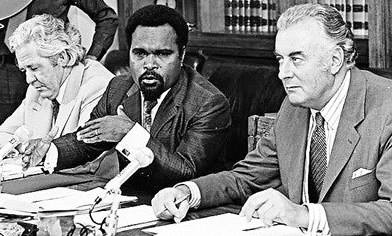

Territories Minister Bill Morrison, Michael Somare and Gough Whitlam at a press conference at Parliament House, Canberra January 1973 © https://www.pngattitude.com/2021/03/sir-michael-the-loss-of-a-giant.html

In the elections for the third legislative assembly, three main parties contested: a conservative United Party, the business-friendly People Progress Party and the Pangu Party, led by Michael Somare. The latter two parties joined forces to form a coalition government in 1972. Somare wanted independence as soon as possible. He opposed many critics who preferred to wait a few more decades before ending the Australian mandate.3 Without giving up his ambitions, Somare nevertheless recognised the many difficulties of his project. In his view, Australia had not fostered the emergence of a Papuan national consciousness,4 nor had it enabled the education of a sufficiently large body of public officials to be in charge of the country.5

Well aware of this disadvantage, Somare must also juggle with the many secessionist political associations that want independence for their region. Its slogan reflects the need to achieve national unity: "One name, one country, one people". What was important for Somare in the early 1970s was to create a desire in the hearts of Papuans to build together, despite the many ethnic and cultural disparities. Let's recall here a key figure on the plurality of Papuan identities: 830 languages are spoken in Papua New Guinea, by populations with very different ways of life (living in the highlands, in coastal regions, or on the river banks).6

This cultural wealth and these disparities explain the numerous debates linked to the creation of the Constitution of Papua New Guinea, especially the one focusing on Papuan citizenship. Initially envisaged only for children with both Papuan parents and grandparents, it was soon realised that some members of the assembly could not even become Papuans themselves. The proposal supported by Somare for a multi-ethnic society granting citizenship more broadly was eventually adopted. Another topic of debate were foreign investments in the country. Somare, who wanted to encourage foreign investment, was opposed by John Momis and John Kaputin, two other emblematic figures for independence, who were mostly concerned with protecting the island's natural resources and firmly opposed to Somare's more liberal vision.7

Despite these disagreements, a consensus was eventually reached. The constitution was finally adopted on 15 August 1975. It guaranteed all Papuans equal rights, freedom of expression and placed the development of men and women free from domination as its primary objective.8 As in all Commonwealth countries, the Queen of England was the official head of state, represented by a Governor-General and a Prime Minister. One month later, on 16 September 1975, the Australian flag was lowered in the capital, and replaced by the flag with the bird of paradise and the southern cross. The country was finally independent, after years of work and negotiations. However, there was very little joy on the ground! For most of the island's villagers, it was just another day, and the changes linked to independence were hardly noticeable in the countryside, which continued its routine life. Without any clashes or violence, Papua New Guinea had become one of the first independent nations in the Pacific... But there was still a lot of work to be done in the country. Economically, for example, the country was still very dependent on Australia: in 1975, 40% of PNG's budget still comes from the former colonial power, a figure that only fell slightly in the following decades.9 Another source of concern was that the national and cultural unity was only theoretical, and Papuans rarely identified with their new nation.

September 16, 1975: Raising of the Papua New Guinea flag at Independence Hill © https://papuanewguinea.travel/png-independence-anniversary

The promise of independence raised questions about the cultural policies of the future country. Michael Somare played a key role in promoting a national culture. But how to define a national culture when the territory has such a great multiplicity of cultures? In this context, Somare's childhood was of particular benefit to him in this endeavour. Born in Rabaul, New Britain, he was the son of a policeman from Wewak. He grew up between these two cultures, learning three languages (Tok Pisin, Kuanua and Murik) at an early age. As a young man, he encountered Japanese forces on the north coast of New Guinea and later Australian forces.10 Somare's childhood was thus marked by encounters with different cultures, which influenced him greatly in his future political career. In his autobiography, he showed how these experiences helped him to develop this appreciation of a united culture and nation:

“One of our greatest and most urgent tasks in Papua New Guinea today is to forge a new national unity out of the multiplicity of cultures. In such a situation it is a distinct advantage to have been exposed to two cultures in one’s childhood. I always thought of myself as having two homes.”11

After his appointment as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Port Moresby National Museum in 1969, the promotion and the protection of the nation's cultural heritage became a major issue in Michael Somare's career. This museum, the heir to the hopes of Governor Hubert Murray, was established in 1954.12 Establishing control over national cultural properties and the management of the collections and the national museum became a means of asserting a desire for power change and the promotion of nationalist policies. Michael Somare was particularly concerned at the time with the draining of cultural items to Europe, Australia, and the USA. One of the major examples is the Seized Collection. In June 1972, 17 cases were seized by customs just before leaving the country. Each box contained artefacts of historical, artistic, or spiritual significance. One of them contained a mask from the Wewak region, Michael Somare's home region. The collection was eventually transferred to the National Museum in Port Moresby for display.13

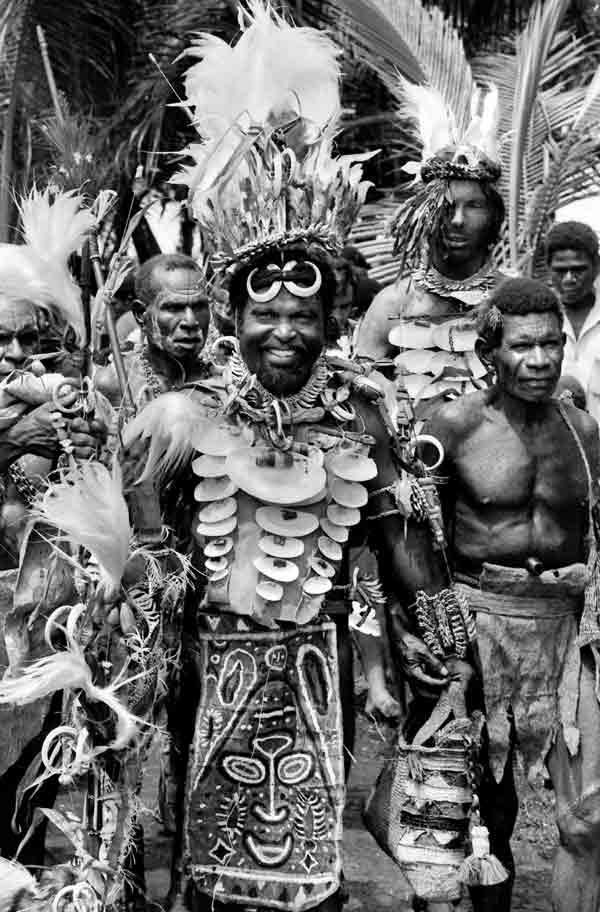

Sir Michael Somare after his initiation as Sana wearing yamdar ornaments, in Karau village, on December 1973 © Veronica Peek

Michael Somare was very concerned about the looting of the national heritage, a concern that is highlighted in his autobiography. In particular, he describes his animosity towards the missionaries who looted objects from the men's houses ( haus tambaran) in the 1920s.14 He also described his first opposition to the white man when missionaries broke sacred flutes in his village.15 Michael Somare's cultural policy was particularly concerned with protecting the national heritage thanks to the modern institutions set up (the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies or the national museum, for example) while respecting local customs and authorities. In this respect, the example of the kakars figures is particularly interesting. Particularly anxious to keep a trace of these sacred artefacts, he negotiated with the gapars, the initiated people who had authority over the objects, to be able to photograph them. Somare was too young and therefore uninitiated to see the objects, but he went with the older Professor Ulli Beier. Somare's account of this episode shows the enormous sacrifice made by the gapars. By letting him see and photograph these objects, they could no longer be gapars and thus initiate the next generation to this position.16

The promotion of a national cultural policy was particularly helped by the Australian government's donation of AU$5 million over 5 years from 1973.17 This money was invested in the national museum and also in the creation of various cultural institutes established in 1963: the University, the Institute of PNG Studies, and a Creative Arts Centre.18 The national cultural policy attempted to promote contemporary artists. These artists were described by Michael Somare and Bernard Narakobi as "national treasures".19 This development of national contemporary art was also linked to the presence of two expatriates. The first one was Tom Craig, a visual arts teacher in Goroka. The second one was Georgina Beier, a teacher at the University of PNG since 1967. Her students include Timothy Akis, Ruke Fame, and Mathias Kauage, major figures in emerging national contemporary art.20

Georgina Beier, together with her husband Ulli, were key figures in the development of national culture at the time of independence. They first worked in Nigeria with the Yoruba people, developing their arts and literature. They then went to PNG to teach at the university in 1967.21 Ulli Beier met Sir Albert Maori Kiki, another founding member of Pangu Parti, at Brisbane airport. Their meeting led to the publication of Maori Kiki's autobiography in 1968, Ten Thousand Years in a Lifetime: A New Guinea Biography.22 This was followed by Michael Somare's publication in 1975, Sana: An Autobiography of Michael SomareBoth stories are of course closely linked to the nationalist and anti-colonial political context, but they also echo a national context of great creativity in all fields: visual arts (Kauage, Fame or Akis), theatre (Arthur Jawodimbari), poetry (the Papua Pocket Poets series) but also fiction.23 Ulli Beier published the first national fiction novel, The Crocodile, written by Vincent Eri in 1970.24 These creations capture a context of transition, hope, and excitement about a change in power. Somare's autobiography is particularly interesting in this respect because, although written in English, it emphasises the importance of traditional knowledge and value systems (note, for example, the importance of the Tok Pisin terms which are not always translated) and the importance of different cultures coming together to form a strong, united nation. Conflict resolution through discussion is particularly valued. Michael Somare appears both as an important political figure and as Sana, the title of authority in the Wewak region. Sana Michael Somare is the one who resolved the conflicts of a modern nation while respecting traditional knowledge and customs.

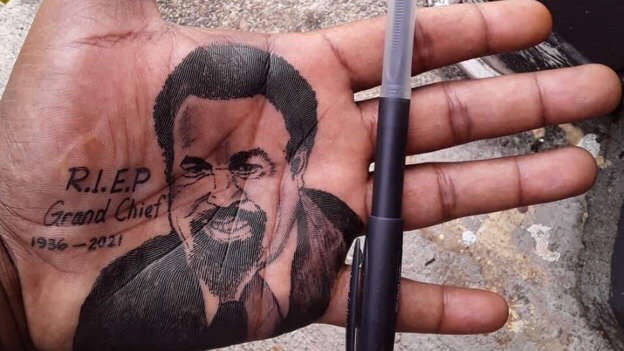

Ink portrait of Sir Michael Somare in the hand of the artist Derrick Lendu, shared on social media on the 3rd of March 2021 © Derrick Lendu

It is easy to understand why Sir Michael Somare was and still is so important to PNG. His tragic death in February this year was followed by a large number of gatherings, including artistic creations in his memory. A portrait of Somare done in ink in the palm by art student Derrick Lendu has been circulating widely on social media.

“The name Somare was the name we often hear when you're small, growing up, so when he passed on we faced a great loss to the country […] We appreciate what he did for the country in achieving independence and everything in his life ... so I felt like I should do a proper tribute.”25

Camille Graindorge et Enzo Hamel

Cover picture: Sir Michael Somare breaking an arrow to show the friendship between Papua New Guinea and Australia before giving a piece to Whitlam and another to Oala Oala-Rarua. Sitting behind him, Albert Maori Kiki and Senator Don Willesee as well as three Mekeo dancers. Photograph taken by Australian Investigation Services © SOMARE 1975

1 RéMichael Somare's answer to Anto Parao in 1972 who wished for a later independence, In WAIKO, 1993, p.183.

2 ZIMMER-TAMAKOSHI, 1998, p.6.

3 Especially foreigners who wanted to protect their commercial interests but also the conservative United Pary. WAIKO, 1993, p. 192 et 183.

4 DERLON, 1999, p. 76.

5 Et en effet : “[…] les politiques australiennes en matière d’éducation avaient été si peu performantes qu’en 1960, un quart seulement des enfants en âge d’être scolarisés allaient à l’école primaire, et qu’aucun d’entre eux n’avait pu atteindre les deux dernières années de l’enseignement secondaires dans une école des Territoires.”, DERLON, 1999, p. 76.

6 6 BRUTTI, 2007, p. 36.

7 WAIKO, 1993, p. 189.

8 Préambule de la Constitution de la Papouasie Nouvelle-Guinée, [en ligne] , https://perspective.usherbrooke.ca/bilan/servlet/BMDictionnaire?iddictionnaire=1755.

9 WAIKO, 1993, p. 196.

10 SOMARE, 1975, p. 1-14.

11 SOMARE, 1975, p. 1.

12 COCHRANE, 2011, p. 255.

13 CRAIG, 1992, p. 1543.

14 SOMARE, 1975, p. 13-14.

15 SOMARE, 1975, p. 41.

16 SOMARE, 1975, p. 30.

17 SMIDT, 1977, p. 227.

18 COCHRANE, 2011, p. 255.

19 ROSI, 2002, p. 241

20 ROSI, 2002, p. 244.

21 TRIST, P. in BEIER, 2005, p. xiii.

22 BEIER, 2005, p. 21-27.

23 RITCHIE, 2015, p. 23.

24 WINDUO, 1990, p. 37.

25 STÜNZNER, I. & N. FOGARTY, 2021

Bibliography:

- BEIER, U., 2005. Decolonising the Mind: The impact of the University on culture and identity in Papua New Guinea, 1971-74. Canberra, Pandanus Books.

- BRUTTI, L., 2007. Les Papous, une diversité singulière. Paris, Gallimard.

- COCHRANE, S., 2011. “Mr Pretty’s Predicament: Ethnic Art Field Collectors in Melanesia for the Commonwealth Arts Advisory Board, 1968-1973.” In QUANCHI, M. & S. COCHRANE (eds.) Hunting the collectors : Pacific collections in Australian museums, art galleries and archives. New Castle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, pp. 235-266.

- Constitution de la Papouasie Nouvelle-Guinée, [en ligne] , https://perspective.usherbrooke.ca/bilan/servlet/BMDictionnaire?iddictionnaire=1755.

- CRAIG, B., 1992. “National Cultural Property in Papua New Guinea: Implications for policy and action.” Journal of Anthropological Society of South Australia, vol. 30, no 2, pp. 1529-1554.

- DERLON, B., 1999. “Traditions et politiques de l’Etat en Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée : le cas de la province de Nouvelle-Irlande”. Journal de la Société des Océanistes, Vol. 109, No. 2, pp. 71-81.

- RITCHIE, J., 2015. “Political Life Writing in Papua New Guinea What, Who, Why?”. In CORBETT, J. & B. V. LAL (eds.) Political Life Writing in the Pacific: Reflections on Practice. Canberra, ANU Press, pp. 13-31.

- ROSI, P. S., 2002. “ »National Treasures » or « Rubbish Men »: the disputed value of contemporary Papua New Guinea (PNG) artists and their work”. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 241-267.

- SOMARE, M., 1975. Sana: An Autobiography of Michael Somare. Port Moresby, Niugini Press

- STÜNZNER, I. & N. FOGARTY, 2021. “PNG pays tribute to Sir Michael Somare with hand, hair and oil portraits”. ABC radio, 12 March 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/radio-australia/programs/pacificbeat/png-somare-art/13241688

- SMIDT, D., 1977. “The National Museum and Art Gallery of Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby”. Museum International, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 227-239

- WAIKO, J., 1993. A short history of Papua New Guinea. Melbourne, Oxford University Press Australia.

- WINDUO, S. E., 1990. “Papua New Guinean Writing Today: The Growth of a Literary Culture”. Mānoa, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 37-41.

- ZIMMER-TAMAKOSHI, L., 1998. Modern Papua New-Guinea. Kirksville, Thomas Jefferson University Press.