In the Eye of the Crocodile1 begins with a story of an 'encounter'2 between the author, Val Plumwood (born Val Morell, 1939-2008) and a crocodile. This 'encounter' takes place in the Northern Territory of Australia, in 1985, on the East Alligator River in Kakadu National Park. Plumwood, a connoisseur of the area, set out on a new trail, prepared by ranger Greg Miles, who offered to test it before it was opened to the public. Heavy rains, however, swelled the waters which soon erased the marks on the trail. Deciding to return, Plumwood suddenly spotted what looked like a stick:

As the current moved me toward it, the stick developed eyes. A crocodile! It did not look like a large one. I was close to it now but was not especially afraid; an encounter would add interest to the day. Although I was paddling to miss the crocodile, our paths were strangely convergent. I knew it would be close, but I was totally unprepared for the great blow when it struck the canoe.3

I won't tell the rest of the story in detail (I'd rather let you read it), but it is violent: Plumwood suffers the 'death roll'4 of her predator who, in the end, abandons her prey. She makes her way back to shore and is eventually found by her ranger friend. But more than violent, what follows is transformative for Plumwood, who writes: "I knew I was food for crocodiles, that my body, like theirs, was made of meat. But then again, in some very important way, I did not know it, absolutely rejected it ".5

When I first read this woman's story, I immediately thought of anthropologist Nastassja Martin's - as many ethnology students probably would have done, since the publication of her story published in 2019, In the Eye of the Wild.6 The latter did not 'encounter' the teeth of a crocodile, but the jawbone of a bear while walking in a forest on the Russian Kamchatka Peninsula. In this case, "the event [was] not: a bear attacks a French anthropologist [...]. The event [was]: a bear and a woman meet and the boundaries between worlds implode".7 As with Plumwood, Martin's experience was transformative or, in her words, provoked a rebirth that invites her to "live again"8 , differently, with the world.

I think I am alone, but I am not. A bear just as confused as I am is also walking on these heights [in the heart of the glaciers] [...]. We bump into each other [...]. When I see him he is in front of me, he is as surprised as I am. We are two metres apart, there is no escape for him or for me [...]. We collide, he makes me topple over [...].9

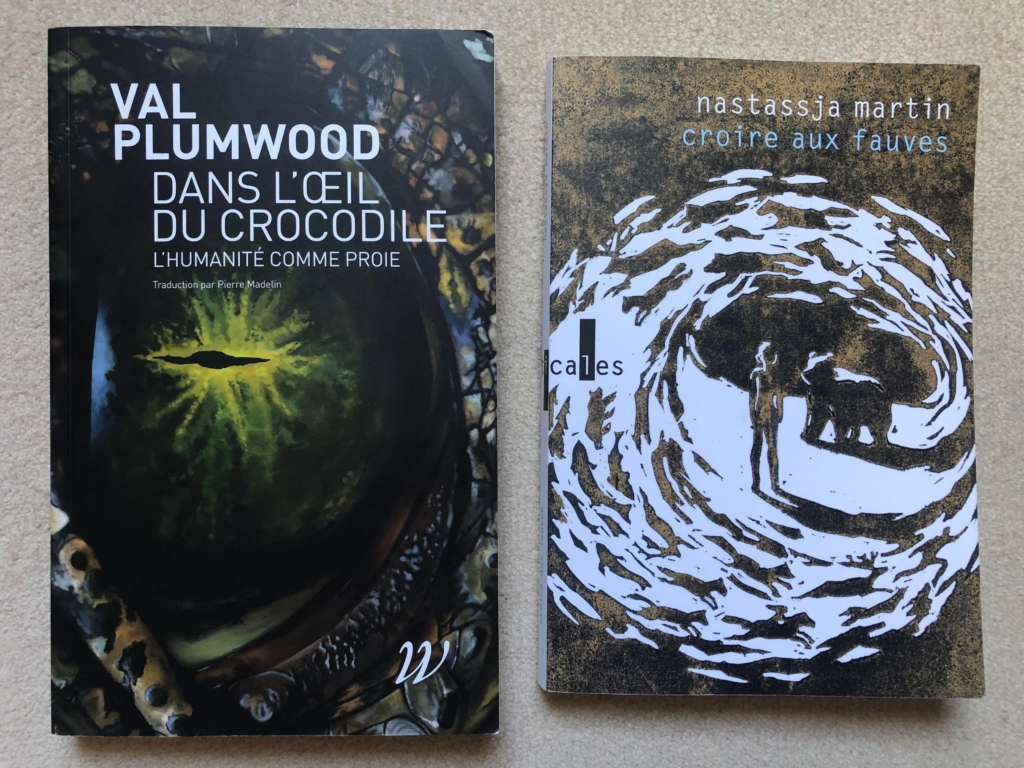

Dans l’oeil du crocodile and Croire aux fauves © Garance Nyssen

Nastassja Martin is a French anthropologist who first did her PhD at the École des Hautes Études en Sociales (EHESS, Paris) with the Gwich'in in Alaska, then continued her research with the Evens in Kamchatka, Siberia, where she 'met' a bear in 2015. For the Evens, with whom she lived in this Russian end of the world, she then became miedkha, half bear, half woman.sup>10 Before this 'encounter', she was already matukha, bear, because she likes blueberries and, above all, she often dreamt of bears.11

After her 'encounter' with the crocodile, Val Plumwood was often nicknamed 'crocodile woman' by her contemporaries, which she did not like.12 Plumwood was not an anthropologist but an Australian ecofeminist philosopher13 whose ecosophical thinking14 marked the intellectual landscape from the 1970s until her death in 2008. Beyond this academic profile, Plumwood was an ardent activist who defended forests and certain animals, such as wombats.15 The Fight for the Forests is the book that made her and her husband, Richard Sylvan (born Richard Routley, 1935-1996), famous. The couple wanted to break away from Western philosophy and think differently about the forest as an ecosystem. Plumwood makes a feminist contribution, pointing out that historically, in the West, the contempt for women and the contempt for nature/earth only fed off each other insofar as women were considered inferior because they are close to nature and nature can be exploited because it is feminised. Plumwood adds that this value system forces other categories of beings to be inferior (indigenous people, workers, etc.), all within a complex hierarchy.16

After divorcing her husband a few years before her 'encounter' with the Kakadu crocodile, Plumwood decided to stay in the house they had built with their own hands, in the mountain south of Canberra. She changed her surname to the name of a tree on the mountain: the plumwood (Eucryphia moorei). In doing so, she embodied her "commitment to a particular geographical place, to which [she] feels [she] owes her identity". This is what she calls 'bioregionalism', which was inspired in particular by Australian Aboriginal thought.17

Plumwood was slow to write about her 'encounter' with the crocodile. She began to do so in 1996, eleven years later, although for philosopher Kate Rigby, who was Plumwood's student, her mentor probably thought of writing about the experience in the days that followed, from her hospital bed.18

When Plumwood died in 2008, her close circle assumed that she was working on a book about the event. Lorraine Shannon, her editor, eventually found three chapters in her computer files that were more or less complete. Shannon decided to publish them anyway - although the third chapter came to an abrupt halt. They were accompanied by earlier writings whose themes resonated with those from her story with the crocodile: the question of predation and the position of humans in the food chain; and communication with non-humans, such as animals or stones.19 With her husband, Plumwood had, as early as the 1970s, put forward the idea that in Western culture, other beings "can only be taken into consideration insofar as they are useful".20 The Eye of the Crocodile was also an opportunity to publish texts that evoked ecological animalism, referring to her theory that reverses this utilitarianism of beings (non-human and sometimes human), based on the nature/culture dualism. I would like to digress for a moment: this dualism refers to a particular way of seeing the world, called naturalism or multiculturalism, depending on the authors. In short, in the West, we tend to classify things in two categories that do not interpenetrate: the natural and the cultural, the latter dominating the former. If you're interested, Casoar has already mentioned the subject here.

Returning to Plumwood, her theory of ecological animalism is, on the contrary, based on "a dialogical ethic [based] on sharing, negotiation and cooperation between humans and animals".21 Finally, as death has been a particular feature of the philosopher's life, she has given it much thought, and the book therefore closes with a reflection on this subject. She places death in the continuity of her conception of the place of humans within the food chain: prey when they are alive, they continue to be prey when they are dead. In short, a dead body is food for other beings and it is necessary to rethink our funeral rituals.22

Martin and Plumwood are different. One is an anthropologist, the other was a philosopher, and they live/have lived their academic and personal lives at different times and in different places. However, they are both attentive to the beings that live around humans, as well as to those humans (and particularly humans for Plumwood) who suffer the results of patriarchy, colonisation, conversions and the debris of extractivist capitalist policies.

Is Nastassja Martin an ecofeminist? I wouldn't venture to answer yes or no. But her position as a woman, as a researcher, as a miedkha in this embrace with the bear, and the descriptions of her relationships with her "informants" (like Daria), in the field, make me want to associate her with those narratives that women have been formulating for a long time now, inviting their listeners to "live further" - jit dalché, in Evene -, that is to say to "maintain a form of communication with the beings that share the world".23 Martin explains that we need to think of the "common[s]"24, that which binds beings together, even if what binds us together today is often unpleasant: climate change, for example; or Covid-19, which has shattered our untouchable certainties as it gallops across the globe. From these often ruined borders, other things could emerge. From the implosion of worlds resulting from the 'encounter' between Martin and the bear, many new things seem to have been born. In In the Eye of the Wild and in other more academic publications, Martin reveals personal as well as epistemological and methodological reflections for anthropology.

The editors of the introduction to In the Eye of the Crocodile consider that Plumwood's 'encounter' with the crocodile "obviously [gave] her, as a philosopher of ecology, an exceptional legitimacy to talk about death and its place in nature".25 I am not sure that this 'encounter' immediately constituted a particular legitimacy, from Plumwood's perspective. The identity turmoil caused by Martin's 'encounter' with her bear, as recounted by the anthropologist, may suggest that it also existed for Plumwood - though certainly in a different way.26 The legitimacy of writing, of feeding this experience into her (personal and) scientific thinking, does not seem to have been immediately self-evident for Martin. The time it took Plumwood to write about her story is perhaps (but this is only my hypothesis) the result of this crisis of personal qualification and this new effort to situate herself in the world.

Finally, both Plumwood and Martin use the narrative mode to tell their stories.27 This alternative form to academic writing aims to reach a wider readership, taking a more sensitive form. As I said, their trajectories are not the same, nor are their goals, but when I read them, I found that what connected them was also this way of writing.

In her later years, Plumwood focused on ecocriticism, that is, the way nature/land is depicted in literature and the power of the written word to produce new narratives that allow us to change our relationship to the world.28 For her part, Martin calls for the provocation of 'encounters' between disciplines to find alternatives to academic writing. It is necessary, she argues, to give voice to those who do not have it and to tell not only the conclusions of a research project but also its context.29 In the Eye of the Wild and In the Eye of the Crocodile are two books constructed on narrational mode that allow us to engage in these projects and put in motion both Western philosophy and anthropology.

My readings have led me to briefly introduce Val Plumwood and Nastassja Martin jointly, which is perhaps not a very well-founded academic connection, but never mind! Their works have touched me because of their form, that of the narrative, which is no less instructive than an academic text (it is perhaps even more so!). Despite their differences, both of them propose, from the stories of their fracturing but creative 'encounters' (animal, human, etc.), another way of thinking about oneself, in which it is advisable to accept what binds us to worlds.

Garance Nyssen

Cover picture: Detail of Val Plumwood's canoe, repaired following 'her' encounter with the crocodile. The boat is held in the collections of the National Museum of Australia under the inventory number 2012.0031.0001 © National Museum of Australia

1 PLUMWOOD, V. (trad. Pierre Madelin), 2021. Dans l’œil du crocodile. L’humanité comme proie. Marseille, Editions Wildproject. This book was first published in English in 2012 by ANU Press under the title The Eye of the Crocodile. It is available as a free download here: https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/eye-crocodile.

2 To use the title of Chapter 1: « Rencontre avec le prédateur », dans Ibid, p. 27.

3 PLUMWOOD, V., 1996. « Being Prey », Terra Nova, vol.1, n°3, pp. 32-44.

4 Marine crocodiles drown their prey several times in water before eating it.

5 PLUMWOOD, 2021, op. cit., pp. 29-30.

6 MARTIN, N., 2019. Croire aux fauves. Paris, Gallimard.

7 Ibid, p. 137.

8 MARTIN, N., 2016. « Vivre plus loin. Une rencontre d’ours chez les Even du Kamtchatka », Terrain, 66, pp. 142-155, p. 154.

9 MARTIN, 2016, op.cit., pp. 149-150.

10 In her account, Martin specifies that this term, not without bringing with it its ambivalences, refers to those who "live between the worlds", human and animal. MARTIN, 2016, op.cit., p. 35.

11 MARTIN, 2016, op.cit., p. 146.

12 « Part of the feast: the life and work of Val Plumwood, a celebration of Val’s life and legacy », 7 mai 2013, National Museum of Australia (Canberra), https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/collection/highlights/val-plumwood-canoe, accessed on 21/06/2022.

13 For an introduction to ecofeminism see, HACHE, E., (dir.), 2016. Reclaim. Recueil de textes écoféministes. Paris, Cambourakis, pp. 13-57. The texts published in this book date mainly from the 1980s, before the institutionalisation of ecofeminism - that is, its entry into the academy - in the 1990s. "In philosophy [Plumwood's discipline], ecofeminist thinking is reformulated in the field of environmental ethics', which leads to the erasure of the political aspect of early ecofeminist voices and often to an absence of references to its beginnings (ibid: 28).

14 This concept, founded in the 1960s by the philosopher Arne Næss (1912-2009), aims to rethink the place of humans in the world. Næss considers that humans do not dominate living things, but are an integral part of them.

15 Wombats (Vombatidae) are marsupial mammals that live in the forests of Australia. In this regard, I invite you to read the touching and instructive chapter in PLUMWOOD, 2021, op.cit. "A wake for a wombat: in memoriam Birubi': 97-106, memoriam to Birubi, the wombat with whom she shared much of her life.

16 RAÏD, L., 2015. « Val Plumwood : La voix différente de l’écoféminisme », Cahiers du Genre, n°59 (2), pp. 49-72, p. 56.

17 Ibid, p. 69.

18 PLUMWOOD, 1996, op.cit. ; Kate Rigby dans, « Part of the feast: the life and work of Val Plumwood, a celebration of Val’s life and legacy », 7 mai 2013, National Museum of Australia (Canberra), https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/collection/highlights/val-plumwood-canoe, accessed on 21/06/2022.

19 Lorraine Shannon dans ibid.

20 FREYA et al. dans PLUMWOOD, 2021, op.cit., p. 16.

21 The author also contrasts ecological animalism with ontological veganism, which, in her view, does not break out of the nature/culture dualism. By considering that humans and animals cannot be consumed, ontological veganism places animals outside of 'nature', which according to Plumwood does not allow for an ecological worldview. PLUMWOOD, "Chapter 6: Animals and Ecology, for a Better Understanding", in PLUMWOOD, 2021, op.cit. pp. 147-148.

22 PLUMWOOD, « Chapitre 7 : Insipide : Vers une approche alimentaire de la mort », dans Ibid, p. 180.

23 MARTIN, 2016, op.cit, p. 154. Let us emphasise here, although I will not elaborate on it, that in his narrative Martin borrows an animistic worldview from the Evens. On this notion, see again Alice Bernadac's article for CASOAR: 14 December 2018, "Le guide du routard ontologique", CASOAR, https://casoar.org/2018/12/14/le-guide-du-routard-ontologique/, accessed on 3/07/2022.

24 MARTIN, N., 2021. « Dire la fragilité des mondes. L’anthropologie ou l’écriture du commun », Revue du Crieur, n°18 (1), pp. 4-19.

25 FREYA et al. dans PLUMWOOD, 2021, op.cit., p. 22.

26 MARTIN, 2019, op.cit., p. 56 for example.

27 For Fanny Boutinet and Alix Cazalet-Boudigues, who explore the work of Nastassja Martin, writing is also a remediator here, i.e. it "assumes a therapeutic function". It was perhaps also therapeutic for Val Plumwood. BOUTINET, F., & CAZALET-BOUDIGUES, A., 2022. « L’écriture comme suture dans Croire aux fauves de Nastassja Martin », Les chantiers de la créations, 14, [DOI : 10.4000/lcc.5480], accessed on 03/07/2022.

28 MATHEWS et al., 2021, op.cit., p. 20.

29 MARTIN, 2021, op.cit., pp. 9-13.

Bibliography:

- BERNADAC, A., 14 décembre 2018, « Le guide du routard ontologique », CASOAR, https://casoar.org/2018/12/14/le-guide-du-routard-ontologique/, accessed on 3/07/2022.

- BOUTINET, F. & CAZALET-BOUDIGUES, A., 2022. « L’écriture comme suture dans Croire aux fauves de Nastassja Martin », Les chantiers de la créations, 14, [DOI : 10.4000/lcc.5480], dernière consultation le 3/07/2022.

- MARTIN, N., 2021. « Dire la fragilité des mondes. L’anthropologie ou l’écriture du commun », Revue du Crieur, n°18 (1), pp. 4-19.

- MARTIN, N., 2019. Croire aux fauves. Paris, Gallimard.

- MARTIN, N., 2016. « Vivre plus loin. Une rencontre d’ours chez les Even du Kamtchatka », Terrain, 66, pp. 142-155.

- HACHE, E. (dir.), 2016. Reclaim. Recueil de textes écoféministes. Paris, Cambourakis.

- « Part of the feast: the life and work of Val Plumwood, a celebration of Val’s life and legacy », 7 mai 2013, National Museum of Australia (Canberra), https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/collection/highlights/val-plumwood-canoe, accessed on 21/06/2022.

- PLUMWOOD, V. (trad. Pierre Madelin), 2021. Dans l’œil du crocodile. L’humanité comme proie. Marseille, Editions Wildproject.

- PLUMWOOD, V., 1996. « Being Prey », Terra Nova, vol.1, n°3, pp. 32-44.

- RAÏD, L., 2015. « Val Plumwood : La voix différente de l’écoféminisme », Cahiers du Genre, n°59 (2), pp. 49-72.