If during your holidays or wanderings in the Loire countryside you pass by the town of Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert in the Forez region, don't hesitate to take a break at the Daniel Pouget Museum of Civilisations. This municipal museum, which opened to the public in 1965 and is now a Musée de France, is located in the former priory of this town, at the foot of the Romanesque church. Created by the association of the Friends of Old Saint-Rambert, it aims to discover local civilizations (those of Forez), but also extra-European civilizations. How could a museum located far from the coasts and ports, gather more than 10,000 objects of extra-European art, coming from all the continents? As for many museums of extra-European art inland, thanks to passionate local figures, collectors, travellers...

In addition to a permanent thematically oriented tour, which we will return to briefly, the museum offers a temporary exhibition dealing with the arrival of the objects in the museum and the various concerns surrounding the paths of these objects and the men and women who donated them.

This exhibition, which is currently on display until 30 September but will probably be extended, is entitled "Objet-voyageurs: l'énigme du don". It deals in a comprehensive way with the question of the journey of objects, from their creation to their disposal in the museum's rooms, and even their restitution, taking as subjects of study the objects kept in the museum and the ethnologists, travellers and collectors who donated them.

View ofthe exhibition "Objets voyageurs, l'énigme du don", Musée des Civilisations Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert, 2022, © Margaux Chataigner

Regarding the museum's Oceanic collections, these personalities are mainly Daniel Pouget, founder of the museum, and Madeleine Rousseau, artist, art critic and activist.

Daniel Pouget (1937-2016), ethnologist and museum curator, was co-founder and first director of the museum between 1965 and 1997. He took part in several ethnographic missions, during which he collected numerous objects and stories, from which he drew many works. From the 1960s onwards, he collected for the exhibitions he prepared. Considering the objects as "ethnographic witnesses" and wishing to extend his mission when he left the Museum of Civilization, he founded a private museum, the Convent, Cabinet of Curiosities, in Chazelle-sur-Lavieu, where he exhibited the rest of his collections.1 In his collection, Daniel Pouget develops a link between extra-European practices and those of the Forez region, especially drawing up a comparative study of traditional extra-European and local healing techniques, thanks to the link created with the aboriginal healer Dawidi in the 2000s. He also travelled to the Asmat people in West Papua and to the Trobriand Islands, east of Papua New Guinea.2

Madeleine Rousseau (1895-1980) collected non-European art. In 1966, her collection of African art was exhibited at the museum. At the same time, she built up a substantial body of private archives from her readings of ethnographic texts, some of which are shown in the exhibition.3 After the Second World War, she was editor-in-chief of the magazine Le Musée Vivant , where she published articles on non-European arts. In the salon she held in her flat in Paris after the war, she was involved with French and African intellectuals in the debates on anti-colonialism. Throughout her career, she also campaigned for the opening and accessibility of art to all.

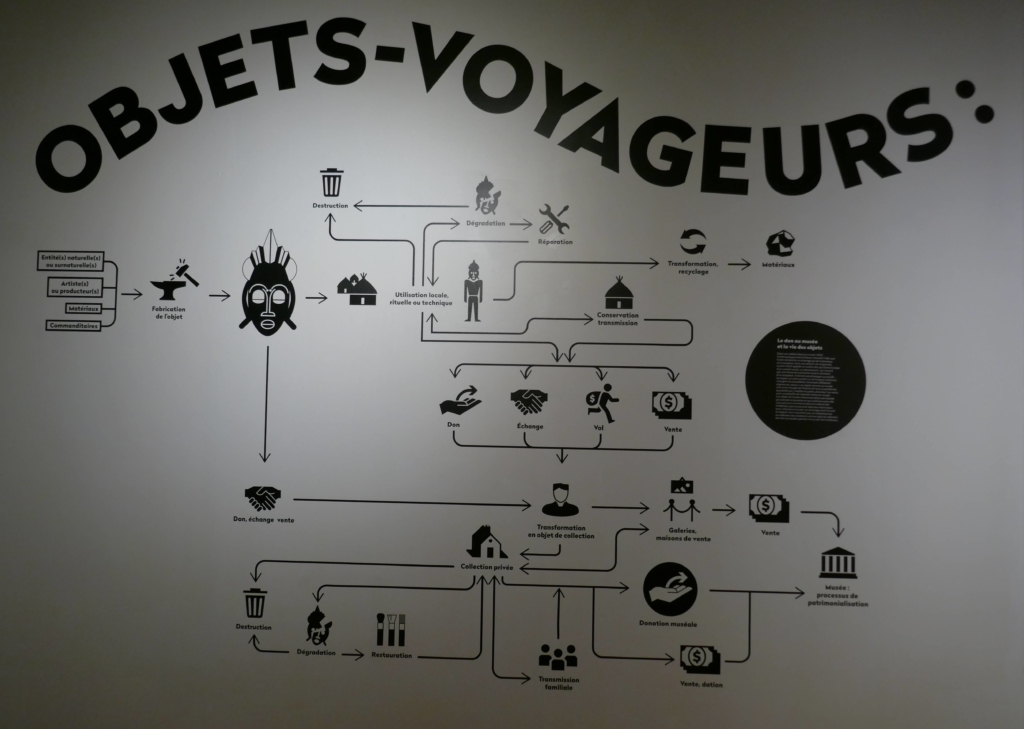

In addition to these fascinating characters,4 the exhibition also focuses on the objects they brought back from their expeditions or collected,4 and their paths to the museum. The texts are concise and the walls are decorated with diagrams and drawings that summarise the journeys of these objects in a very explicit and simple way. The curators raise the question of the "symbolic gift made to a museum", basing their statement in particular on Marcel Mauss'Essai sur le don (first published in 1925) and on the different regimes of value embodied by an object during its life. Evoking Mauss also makes it possible to address, as a thread in the exhibition, the way in which objects take on the history of their successive owners and remain attached to them.5

Introductory diagram for the exhibition "Objets voyageurs: l'énigme du don", Musée des Civilisations de Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert, 2022 © Margaux Chataigner

The diagrams and drawings invite us to understand and observe the complexity of exchanges at different periods. As an example, here is the journey of a Kohau Rongorongo tablet from Rapa Nui: Made by a Rapanui sculptor in his workshop, it is then sold as an example of local art and craft, inspired by traditional objects that are no longer used. Although we have little information on the use of these tablets, they may have been used as memory aids for storytellers, particularly with regard to genealogies. Purchased by Daniel Pouget in 1995, it was brought back for the Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert museum and exhibited, stored and inventoried in 2000 and 2017.

View of the exhibition "Objets voyageurs, l'énigme du don", Musée des Civilisations Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert, 2022, © photo Margaux Chataigner

In each room of the exhibition, a donor and his taste are highlighted, as well as the reasons for his collection (anthropological, scientific, aesthetic...) and numerous objects, some of which have a characteristic path, are highlighted and their trajectory is explained by diagrams similar to those on the Kohau RongorongoThe walls of the exhibition are occupied like a large school board and time is taken to explain everything that seems important for the good understanding of the public.

In addition to the process of production, exchange and the personalities presented, the final part of the exhibition focuses on the role of the museum itself. The curator of the exhibition6 raises the question of the gift to the museum, of a new change in the value of the object through its entry into the inventories and the status of patrimony. However, the exhibition discusses the entry into the museum as the last stage in the life of the object. Works that enter French collections are non-transferable and inalienable, i.e. they cannot be sold or owned by a private actor, in short, they cannot leave the museum's inventory. However, with the current issues of restitution and the commitment of museums over the past fifteen years to this approach, the decision to return the object to its home is being considered. The museum takes the example of the Maori heads (Moko Maoris) and their restitution in 2010, but also the more recent legislative framework, and the political implications, especially through the Savoy-Sarr report.7 The information is sometimes complex, but the illustrations on the walls throughout the exhibition make the subject clear and understandable. At the end of the exhibition, the public is invited "Beyond the debate on the merits of restitution, [...] to question the relationship we have with these objects according to our personal and family histories, to the place we give to the counter-gift in the phenomena of cultural appropriation”. The exhibition develops the notion of gift and counter-gift at the level of the visitor and questions his or her link with these modes of cultural exchange.

The didactic aspect of the exhibition is also present during our visit, as the reserves can be visited by the public. On several floors, packaged behind glass, objects from the reserves are on display for visitors to see, some of them semi-dissimulated, inviting curiosity and gymnastics to catch a glimpse of them. These rooms also allow visitors to perceive the backstage of a museum, where objects of all origins rub shoulders. In the case of the Oceanic collections, we discover masks from the Baining of New Britain, tree ferns from Vanuatu, Iatmul pottery from the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea, etc. The problem we encounter in these storerooms is the lack of information about the collections presented. However, this can be justified by the fact that, as a reserve, it does not constitute an exhibition in itself. In addition, in order to preserve the collections, the museum staff is currently carrying out a major inventory and packaging exercise, which will lead to the concealment of a large number of objects in conservation boxes.

Mask of the Baining of New Britain, view from the storeroom of the Musée des Civilisations Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert, 2022, © Margaux Chataigner

In addition to the storerooms and the temporary exhibition space, the museum has several permanent exhibition spaces. One of these spaces is dedicated to a collection of Aboriginal bark and acrylic paintings, probably collected by Daniel Pouget during his stays in Australia. This room, entitled "Aboriginal art, an art of resistance", chooses to underline the role and evolution of Aboriginal painting in echoing their claims to their rights on the Australian territory (On this subject, you can consult an article by Casoar here ).

Painting on eucalyptus bark, representation of an anteater, rooms of the Australian Aboriginal collections, Musée des Civilisations Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert, 2022, © Margaux Chataigner

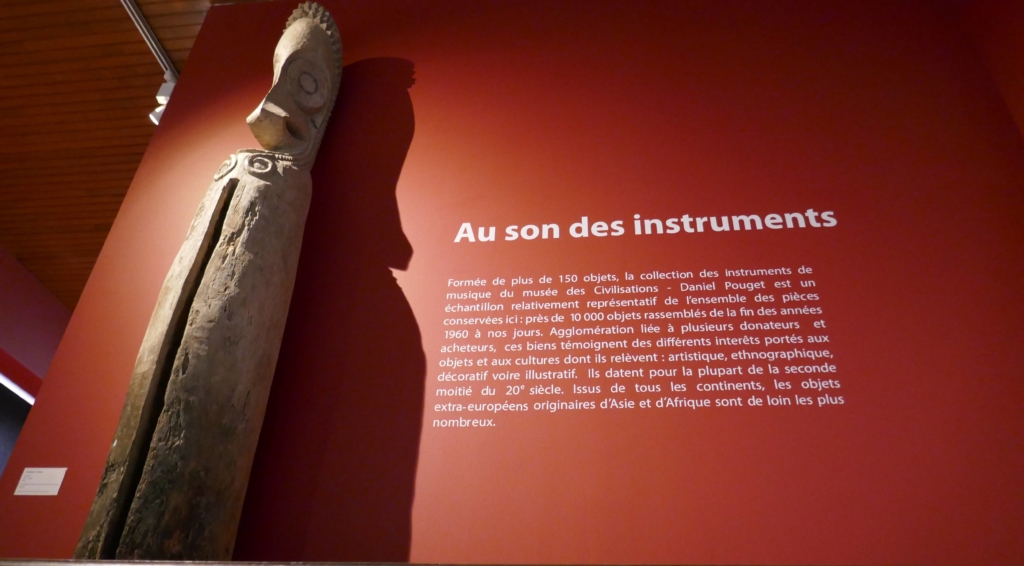

The rest of the permanent exhibitions, in addition to a room of African collections and a room entitled "Beauties of Japan", choose two angles of approach. On the one hand, there is a focus on musical instruments from around the world. A large slotted drum from Vanuatu welcomes visitors. The room text insists on the fact that an object cannot speak for itself, and that one must take into account its manufacture, the way it is played, the sound it produces and its context of use. Without condemning ethnocentrism, which can be a legitimate first angle of approach, it is specified that using one's own references in understanding the culture of the other is however very limiting, and that it is necessary to go beyond this. Finally, several rooms are dedicated to the human figure through the peoples, showing the multiplicity of what it can represent or evoke. Regarding Pacific collections, a tree fern from Vanuatu is presented. This fern does not represent a person or a deity in particular, but rather is a symbol of the person's place and power in a hierarchical social system.

Ambrym slit drum, Vanuatu, musical instruments room, Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert Museum of Civilization, 2022, © Margaux Chataigner

The Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert Museum of Civilization has collected more than 10,000 objects donated since the 1960s to the present day. Daniel Pouget, for whom the museum is now named, played a major role in the creation of these collections and in the discovery of other peoples by the local population. This museum of distant lands, which is not necessarily expected in the heart of Forez, offers fascinating and enriching exhibitions, aimed at a wide audience. The tools used by the museum here are its own collections, their history, and the role of the museum itself as a place of preservation of memory and heritage, but also as a place for discussion of contemporary curating issues and problems, which anyone can understand, if one takes the trouble to explain them.

I would like to thank Audrey and Laurence Paris, director of the museum, for taking the time to talk with me and answer my many questions.

Margaux Chataigner

Cover picture Exhibition rooms of the Australian collections of the Musée des Civilisations Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert, 2022, © Musée des Civilisations - Daniel Pouget, photo by Margaux Chataigner

1 This museum houses, among other things, Oceanic collections.

2 See BOUHIN, P., 1994. "Daniel Pouget ou mémoire d'un voyageur". France 3 Lyon, INA archives.

3 Madeleine Rousseau's archives are kept in the Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert museum.

4 The exhibition presents these donors under several categories: ethnologists, collectors, cooperators, and ordinary travelers. We focus here on those who have a connection with the Oceanic collections.

5 For more information on this writing, see the following article published in Casoar: https://casoar.org/en/2018/12/22/merry-christmauss/

6 The curator of this exhibition is Arnaud Morvan, an anthropologist at the social anthropology laboratory of the Collège de France. This exhibition is the result of two years of research that he conducted on the museum's donors

7 This report, delivered by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr to the President of the Republic in 2018, highlighted the problem of the ownership of 26 works from the Royal Treasure of Abomey, and their restitution from the Quai Branly -Jacques Chirac Museum to the Republic of Benin. In order to proceed with the declassification of these objects (i.e. their removal from public collections), law no. 2020-1673 of 24 December 2020 was adopted. Concerning the Moko Maori, see the Casoar article here.

Bibliography:

- Site internet de la ville de Saint-Just-Saint-Rambert, https://www.stjust-strambert.fr/sorties-et-loisirs/culture-et-evenements/musee-des-civilisations-daniel-pouget/

- BOUHIN, P., 1994. « Daniel Pouget ou mémoire d’un voyageur. » France 3 Lyon, archives de l’INA.

- FLAGEY, H., 27 octobre 2016. « Daniel Pouget : la passion de la découverte et de la rencontre. », Le Progrès, https://www.leprogres.fr/loire/2016/10/27/daniel-pouget-la-passion-de-la-decouverte-et-de-la-rencontre, dernière consultation le 25 juillet 2022.

- BERTHEAS, D., 31 août 2016. « Les aborigènes ont un respect de la vie qui manque à nos sociétés. », Le Progrès, https://www.leprogres.fr/loire/2016/08/31/les-aborigenes-ont-un-respect-de-la-vie-qui-manque-a-nos-societes, dernière consultation le 25 juillet 2022.

- MAURICE, D., 2008, « L’art et l’éducation populaire : Madeleine Rousseau, une figure singulière des années 1940-1960 ». In Histoire de l’art, n°63, Femmes à l’oeuvre, pp. 111-121.