The Casoar team respectfully advises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders people that this article includes images, works and names of deceased Indigenous people and may include images of artistic, cultural or intellectual property that may be of sensitive nature.

*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

Emily Kame Kngwarreye is probably one of the world's best known Aboriginal artists. Her painting Earth's Creation once held the record for the most expensive work by an Aboriginal artist in the world. But did you know that her career as a painter was as short as it was meteoric? And that her artistic work did not begin with painting but with textiles? Today, Casoar takes you on a journey to discover the story of one of the greatest artists of the late 20th century.

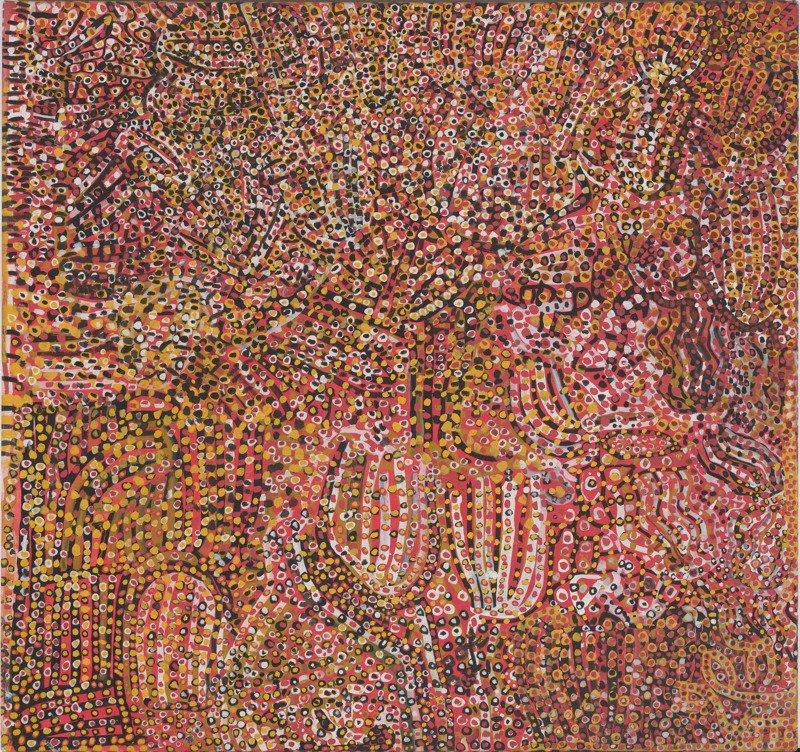

Yam Awely, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1995, acrylic on canvas, National Gallery of Australia

Emily Kame was born around 1910 in the Central Desert, in an area called Alhalkere, about 230 km North of Alice Springs. Alhalkere is a place where the Dreaming paths of several Aboriginal groups cross, including the Anmatyerre, to whom Emily belongs. At the time, Aboriginal people still lead a semi-nomadic life, following the routes traced by ancestral entities during the Dreaming, a mythical time that is at once past, present and future. However, the area was soon appropriated by Western ranchers, without regard for Aboriginal rights to the land, and was named Utopia, the name by which it is still known today.

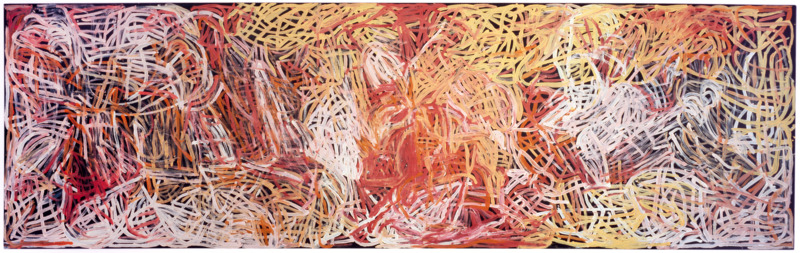

The Alhalkere Suite, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1993, acrylic on canvas, National Gallery of Australia

The Australian government's policy was to force Aboriginal people to settle down and to impose severe restrictions on their rights and freedoms. It should be remembered that on his arrival in Australia in 1770, British Captain James Cook declared the island uninhabited and Aboriginal people have only been fully recognised as Australian citizens since 1967.1

Map of Australia showing Utopia © CASOAR

Like many Aboriginal women at this time, Emily Kame underwent her first arranged marriage and worked as a domestic in the home of a white family - the Purvis at Woodgreen Station. 2 In the late 1930s, however, she remarried, this time for love, and took on what was then considered male work, including looking after livestock.3

Kame, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1991, acrylic on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria

The 1970s saw the development of a vast movement to claim civil and land rights from the Aboriginal populations. In 1967, full Australian citizenship was granted and in 1976, the Aboriginal Civil Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act allowed Aboriginal people to reclaim land which had been looted during colonisation.4 Numerous groups left pastoral properties and urban centres to return to their lands in the form of communities called outstations. Emily Kame and her family joined the community of Utopia.

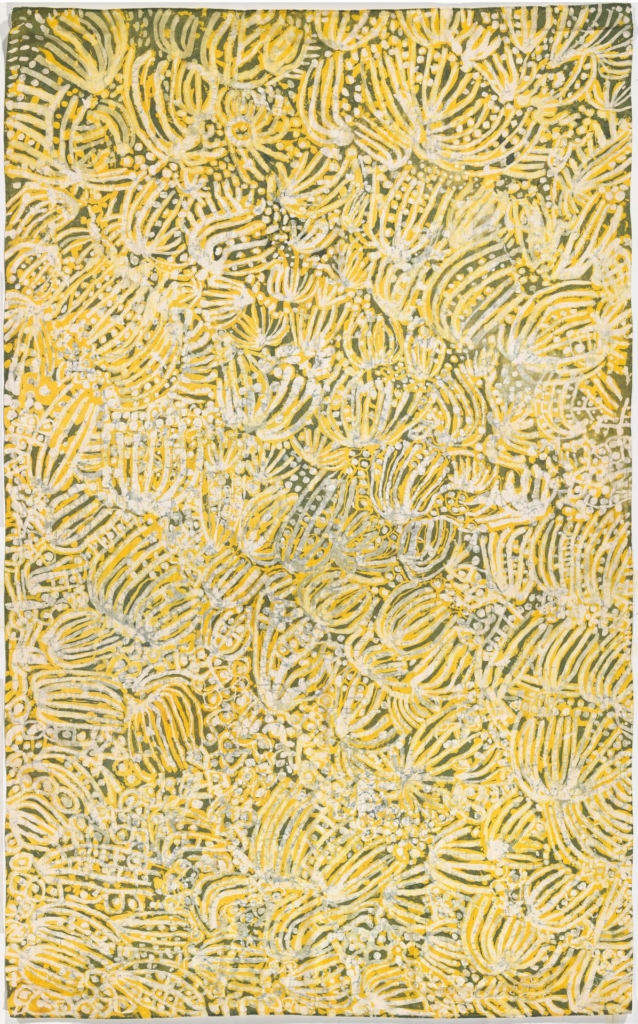

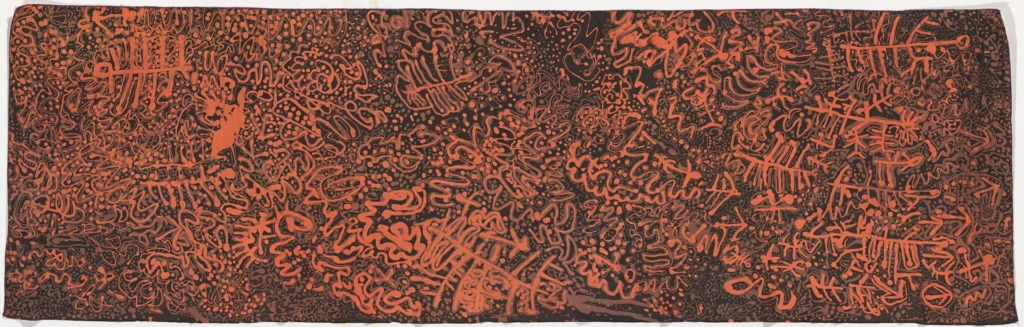

Kame, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1988, batik on silk, National Gallery of Victoria

This outstation quickly became a centre of artistic production. Spurred on by Jenny Green, a Western-born artist interested in the Aboriginal women's way of life. The Australian government funded an education programme in 1977 to teach batik to the women of Utopia. Batik is a textile dyeing technique that involves tracing wax patterns on fabric before dipping it in a dye bath. The wax protects the patterns from dyeing and only the undrawn parts are dyed: this is known as "reserve" dyeing. Artists are free to carry out several successive dye baths, adding or removing motifs each time. Once the dyeing is complete, the fabrics are plunged into boiling water to melt the wax. The women of Utopia quickly learnt this practice, in which they found a source of income and independence but also pride and affirmation of their knowledge.5

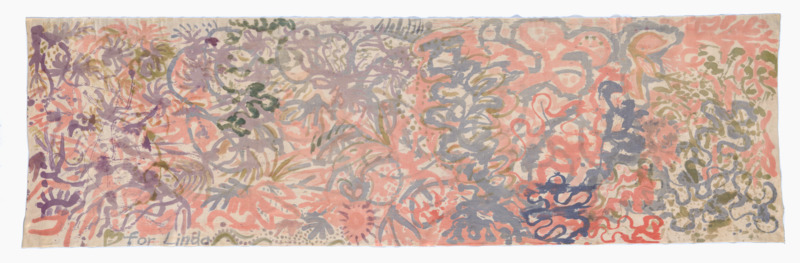

For Linda, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1981, National Gallery of Australia

Indeed, the Anmatyerre women have their own rituals, knowledge and initiation systems, of which Emily Kame, then over 60 years old, was one of the respected leaders. While this female knowledge differs from the rituals practised by the men of the group, it too has its source in the Dreaming and the paths of the ancestral entities. These ancestors have emerged from the ground in various places and shaped the Australian landscape through their interactions, leaving their mark on the place. Through their maternal and paternal ancestry, Aboriginal people are linked to one or more of these 'dreamings' and the places they pass through. Depending on their degree of initiation and knowledge, they can re-actualise the link with this 'ancestral present' through the performance of rituals during which ephemeral works are produced, painted on the ground or directly on the dancers' bodies. The motifs that make up these works are subject to strictly defined rights and not just anyone can represent any dreaming.6

The dreamings of Anmatyerre women are deeply linked to the wildlife elements that are central to their daily activities. In a semi-nomadic lifestyle, Aboriginal women were responsible for harvesting edible plants and hunting small prey, especially lizards. They also had extensive knowledge of medicinal plants. The rituals of the Anmatyerre women therefore give a central place to these elements and to their renewal through the dry season/wet season cycle. These rituals and the related knowledge in the care of Anmatyerre women are referred to as the Awelye.7

Untitled, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1980, batik on silk and cotton, National Gallery of Victoria

It is precisely this knowledge that the women of Utopia choose to represent on their batik, celebrating their knowledge and their connection to their territory. In 1978, they came together to form the Utopia batik women's group, of which Emily Kame was one of the founders along with Kathleen Petyarre, another major artist of the period. This group played a fundamental role in the recognition of the land rights of Aboriginal populations in the Utopia region. In 1979, several Utopia women, including Emily, performed an Awelye ceremony to prove their ancestral link to the area and to support their claims.8 The money from the sale of their batiks also helped to fund this struggle, which led to the recognition of the rights of the Anmatyerre to the Utopia region.

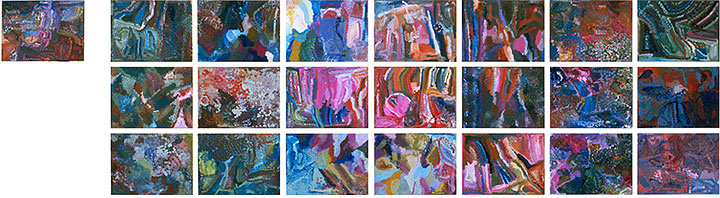

With the help of Julia Murray, artistic coordinator, several exhibitions were organised, including a highly advertised one in 1981 at the Adelaide Festival Centre. Several museums began to acquire the works of the Utopia women, but it was under the impetus of the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) that interest in these pieces exploded. In 1988, Rodney Gooch, artistic coordinator of CAAMA, organised a large exhibition of 88 batiks of the same dimensions entitled Utopia - A Picture Story. The exhibition was a great success and was shown internationally before its entire contents were acquired by the prestigious Holmes at Court Collection in Perth.

Earth’s Creation, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1944, acrylic on canvas, Mbantua Gallery

But although batik sold well, they did not enjoy the same artistic recognition as the paintings produced by Aboriginal men at the same period. In 1988, Rodney Gooch introduced the women of the Women's Batik Group to canvas paint. This marked the beginning of the best-known period of Emily Kame's work. In just eight years, at the age of 75, she produced more than 3,000 paintings, which were a resounding success. In the group's first group show in 1989, A Summer Project, Emily's works were noticed and the following year she had a solo show at the Coventry Gallery in Sydney.

The paintings and exhibitions continued until the artist's death in 1996. In the meantime, she had become a key figure in contemporary art and was chosen in 1997 to posthumously represent Australia at the highly prestigious Venice Biennale alongside Yvonne Koolmatrie and Judy Watson, two other Aboriginal women.9 Her work was to be the subject of a major retrospective at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra in 2008 entitled Utopia. The Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye.

Ntange Dreaming, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1989, acrylic on canvas, National Gallery of Australia

Emily's style in her paintings is very different from that of her batiks. Where the motifs of the fabrics were usually directly figurative, her paintings are less easy to read for a Western observer. There is a tendency to compare Emily Kame to Claude Monet, Willem de Kooning or Vassily Kandinsky. Yet the concepts of impressionism or abstraction do not apply to these works, which are entirely rooted in the culture and ritual practices of Anmatyerre women.9

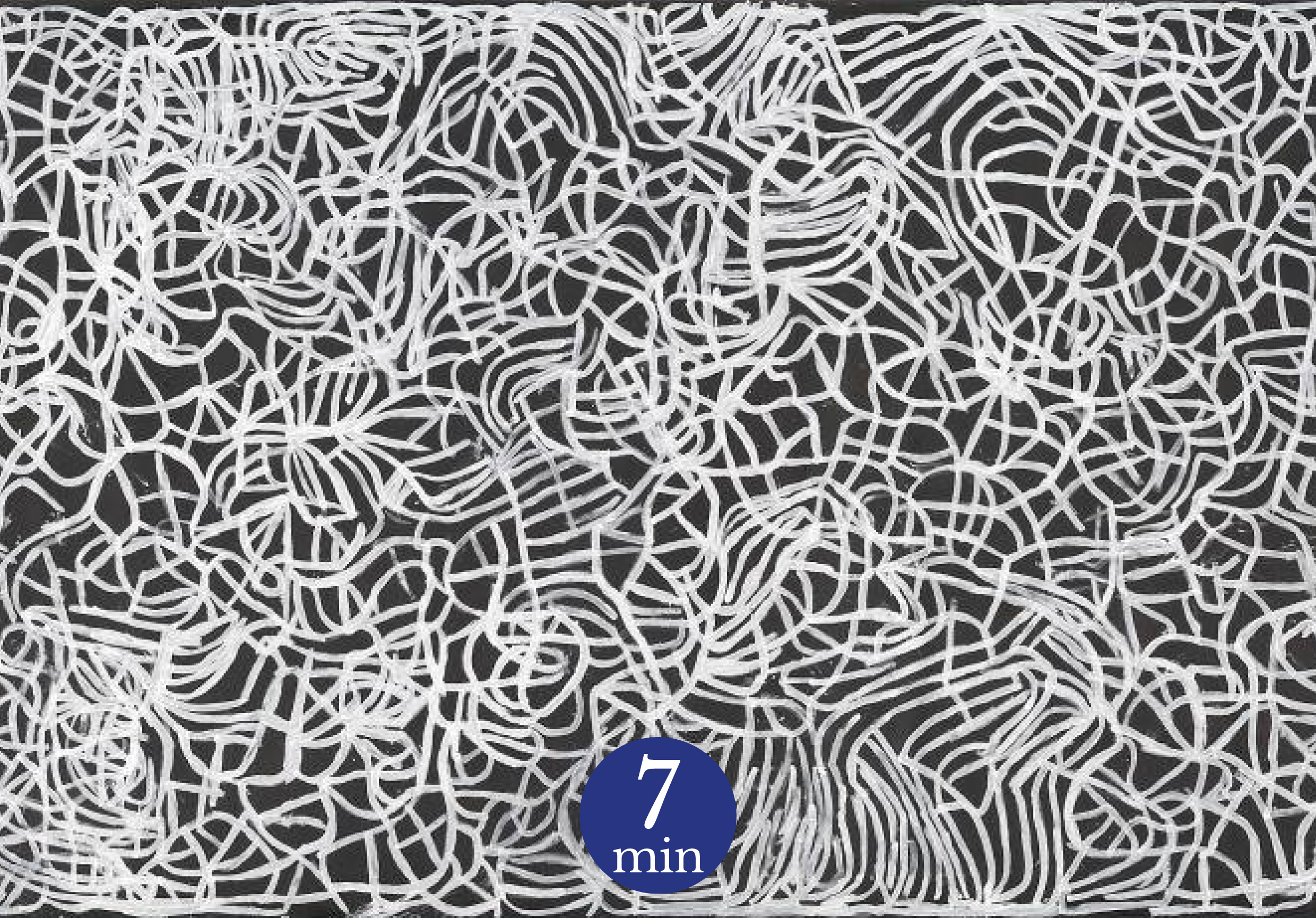

Untitled, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1995, acrylic on canvas, National Gallery of Australia

One can distinguish several periods in her painting. If at the beginning Emily Kame tends to cover her canvases with a multitude of very coloured dots, thick lines gradually appear and unfold on pigmented bakcgrounds and later, on white backgrounds. While one might be tempted to see these as abstract forms and a pure exercise in colour control, the patterns in Emily's canvases are a very concrete evocation of Alhalkere, the region where she was born and where she spent her entire life. The abundance of dots recalls the sudden blossoming of the desert after the rain, while the lines evoke the roots of the bush potato or those of the yam from which the artist takes her name. Kame in fact refers to the seed of the yam in the Anmatyerre language.11

Awely, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1995, acrylic on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria

Like all Aboriginal motifs, they have several meanings, some of which can only be understood by the initiated. They do not come purely from the artist's imagination, but from the patterns traced on the ground or on the dancers' bodies during Awelye ceremonies. The act of painting them constitutes in itself a re-actualisation of the Dreaming and of the link maintained by the artist with the places over which she had the responsibility of watching over as ritual leader. Far from the Western vision of modern art, the artist herself was affirming the meaning of her painting:

"Whole lot, that's whole lot, Awelye (my Dreaming), Arlatyeye (pencil yam), Arkerrthe (mountain devil lizard), Ntange (grass seed), Tingu (a Dreaming pup), Ankerre (emu), Intekwe (a favourite food of emus, a small plant), Atnwerle (green bean), and Kame (yam seed). That's what I paint : whole lot".12

Alice Bernadac

Cover picture: Anwerlarr Anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming), Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1995, acrylic on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria

1 Sur le sujet on pourra consulter nos articles here and here

2 ISAACS, J & SMITH, T., et al., 1998. Emily Kame Kngwarreye Paintings. Sydney, Craftman House.

3 For a good bibliography of the artist, checkout this article

4 For more information regarding the history of legislations please check this article

5 We highly recommend you to watch this amazing video which shows the Utopia women (including Emily Kame) making batiks and receiving Jenny Green's visit

6 For more information on the concept of "dreaming" please look at our article or this easy access book : CARUANA, W., 1994. L’Art des Aborigènes d’Australie. London, Paris; Tames & Hudson.

7 BOUTLET, M. 1991. The Art of Utopua. A New Direction in Contemporary Aboriginal Art. Roseville East, Craftsman House.

8 BELL, D., 2002. « Person and Place. Making Meaning of the Art of Australian Indigenous Women », Feminist Studies, vol. 228. pp. 95-127.

9 The Art Gallery of New South Wales., 1997. Fluent. Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Yvonne Koolmatrie, Judy Watson. XLVII Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte La Biennale di Vennezia 1997, Australian Pavilion 15 June – 9 November. Sydney, The Art Gallery of New South Wales.

10 NEALE, M. 2008. Utopia. The Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Canberra, National Museum of Canberra Press. pp. 31-35.

11 ISAACS, J & SMITH, T., et al., 1998. Emily Kame Kngwarreye Paintings. Sydney, Craftman House. p. 61.

12 BELL, D., 2002. « Person and Place. Making Meaning of the Art of Australian Indigenous Women », Feminist Studies, vol. 228. pp. 95-127. p. 107.

Bibliography:

Two good introductions to Aboriginal art:

- CARUANA, W., 1994. L’Art des Aborigènes d’Australie. London, Paris, Tames & Hudson.

- MORPHY, H., 2003. L’Art Aborigène. Paris, Phaidon.

On Contemporary Aboriginal Art:

- BARWICK, D., MEEHAN, B & WHITE, I., 1985. Fighters and Singers. The Lives of Some Australian Aboriginal Women. Sydney, Boston, Allen & Unwin.

- BELL, D., 2002. « Person and Place. Making Meaning of the Art of Australian Indigenous Women », Feminist Studies, vol. 228. pp. 95-127.

- BIDLE, J., 2007. Breasts, Bodies, Canvas. Central Desert Art as Experience. Sydney, UNSW Press.

- BOUTLET, M. 1991. The Art of Utopua. A New Direction in Contemporary Aboriginal Art. Roseville East, Craftsman House.

- MCCULLOCH, A & MCCULLOCH, S., 2006. The New McCulloch Encyclopedia of Australian Art. Fitzroy, Aus Art Editions.

- MCCULLOCH, S., 1999. Contemporary Aboriginal Art. A Guide to the Rebirth of an Ancient Culture. St Leonards, Allen & Unwin.

Monographs and exhibitions by the artist:

- ISAACS, J & SMITH, T., et al., 1998. Emily Kame Kngwarreye Paintings. Sydney, Craftman House.

- NEALE, M. 2008. Utopia. The Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Canberra, National Museum of Canberra Press.

- The Art Gallery of New South Wales., 1997. Fluent. Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Yvonne Koolmatrie, Judy Watson. XLVII Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte La Biennale di Vennezia 1997, Australian Pavilion 15 June – 9 November. Sydney, The Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Online resources:

https://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/utopia/emily-kame-kngwarreye

https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/aboriginal-land-rights-act

1 Comment so far