*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

This article was first written for the catalogue of the third edition of the Bourgogne Tribal Show, 2018.

It was in 1926 that a young 24-year-old Australian arrived in Papua New Guinea for the first time. Like many others, he was attracted by the easy gold of Edie Creek mine. Far from being an El Dorado, the island was a burden for the Australian administration of the 1920s which had just acquired these German lands as a result of the Versailles Treaty. The hot and humid climate of New Guinea and the supposed poverty of its soil dissuaded the government from investing in this new mandated territory, whose only wealth seemed to have been its population who had become cheap labour for planters and colonial miners. For the administration as well as for the gold miners, the island was hostile, so that very quickly, Michael Leahy, powerless, disappointed and suffering from malaria, had to go back to Australia, without gold. In spite of these first difficulties, the gold fever took him to the coasts of Papua as soon as he recovered. But the wind had turned at Edie Creek: huge companies had taken over the deposits. Individual miners were now a thing of the past. Leahy then turned towards prospection and relentlessly explored the area around Edie Creek, but without any success. He decided to go up the Ramu river towards the steep chain of mountains at the centre of the island. At the time, geographers were certain that the island was made of a single uninhabited range, even though the territory had never been explored. Some gave free rein to their fantasies... This was how Trégance, a late nineteenth-century French navigator, insisted that he had discovered towns where men, governed by a powerful monarch, extracted gold. For the coastal Papuans, the mountains were inhabited by cruel beings and it was perilous to go there.

But none of these rumours dissuaded Leahy from embarking on the adventure. So, in the morning of 26 May 1930, accompanied by another gold digger and fifteen Papuan porters from the coasts, he headed off towards the Bismarck range where the spring of the Ramu river was. But a surprise awaited him there. After a difficult walking day to reach the summit, they discovered a green and fertile valley, a far cry from the inhospitable mountains that people had described! When night came, they were hit by another surprise: they could discern faint lights in the distance. The mountains were indeed inhabited. Were its inhabitants the bloodthirsty beings described by coastal peoples? They spent their first night fearing an attack and were ready to respond. It was on the following morning that inhabitants of the Highlands first appeared. It seemed that both sides were equally afraid, but the natives gradually came closer to these strangers and tried to touch them, as if to ascertain the reality of what they saw. They were obviously astonished. As to Leahy and his walking party, they were stunned to discover a Papua radically different from the swamp that they knew, with huge fenced gardens where sweet potatoes, sugar cane and beans grew in this temperate climate.

Olgenbeng, Nennga, Mélé. Préparation d’un monga, l’assistance, Françoise Girard, juin 1955, tirage sur papier baryté, musée du quai Branly, PP0144874.

The voyage to the South coast of Papua lasted for seven weeks. Everywhere, ahead of them, the group could hear cries in the valleys warning other tribes of their arrival. They were utterly astonished. Because they had never met white people, some thought Leahy and Dwyer were mythical beings. The Mikaru thought that it was Souw, an immortal with white skin who had come to seek revenge by cutting the trees that supported the skies and letting them fall on the population. In fact, the two men were cutting wood to make tent pegs. Others thought that they were beings coming from the sky: their lanterns held pieces of moon and their tents in white fabric were made from the stuff of clouds. But for most of them, Leahy and his companions were dead people whose skin had turned white after death, according to myth. Because the native porters were in the company of white men, some thought that they were family members who had passed away. Surrounded by many local natives, Leahy and his men penetrated further into the Highlands and panned the rivers in search of a new Edie Creek. Some sources reported that most of the natives were convinced that their dead people had come back and the men panning were thought to be searching for their own ashes and remains that had been scattered in the water. After his first crossing, Leahy carried on leading a prospecting party for four years. Everywhere, the Westerners’ behaviour was watched carefully. The natives noticed that there were no women (maybe they were they hidden in the bags) and that men wore clothes (maybe they concealed huge penises like those of some mythical heroes). However, when they spied on white men bathing in the rivers, they did not see any evidence of this. Yet, the excrement of these beings from the sky was different from that of the birds’. When they slept, these supposedly dead beings did not become skeletons again, as said in myths. But Leahy, who understood that he probably owed his survival to the astonishment of the natives, always left before the illusion was shattered, never staying more than one night in the same place.

At the places where the Australians left their waste, which the natives considered as powerful relics, manufactured goods and dog teeth which were coveted in the rest of the island, were of little interest to the natives. Without understanding why, Leah noticed that they granted a great importance to shells as trading currency. So, on his second trip, Leahy brought a lot of shells back. They were very cheap on the coast and they allowed explorers to subsist and carry on their prospecting. But introducing a large number of them made their value drop dramatically, thus disrupting reciprocal exchange systems forever. This was only the beginning of changes to come. As early as 1932, Michael and his brother Dan oversaw the construction of the first airstrip in the Highlands thanks to funding from Goldfield Limited. Before the Second World War, more airstrips were built. Many colonists and missionaries settled and the Australian government was officially represented. From then on, deep changes in languages, in the economy, in the social structure and local beliefs rapidly followed. Today, when passing through Goroka, the East Highlands capital, maybe stopping at its supermarket, sleeping in one of its hotels or flying out of its airport, who would think of the emotion provoked less than 90 years earlier by an intrepid gold digger arriving and brutally challenging a whole universe?

Camille Graindorge & Margot Kreidl

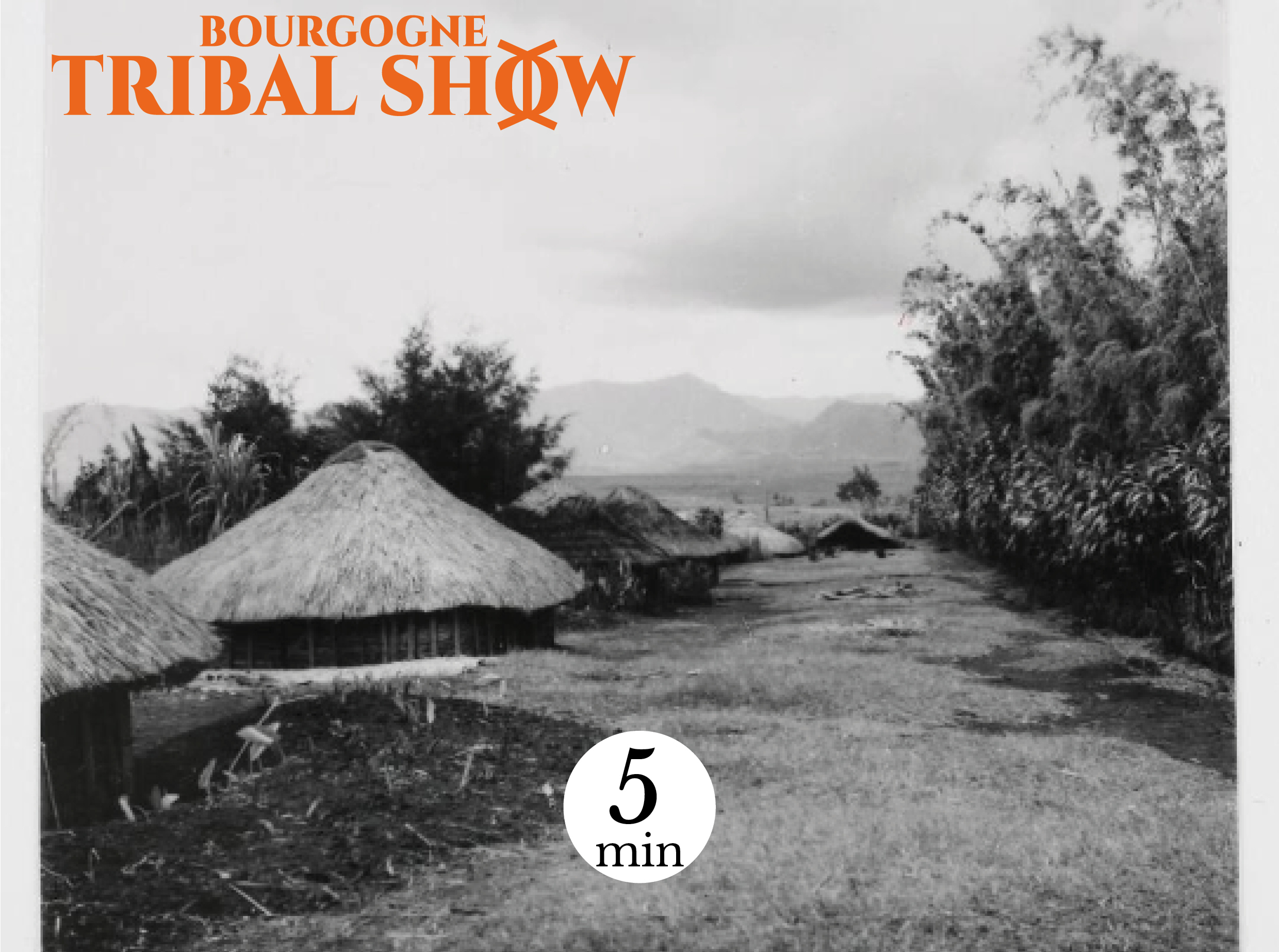

Image à la une : Olgenbeng. Le village chrétien des Nennga, Françoise Girard, juin 1955, tirage sur papier baryté, musée du quai Branly, PP0144878.

Traduction : Béatrice Bijon

Bibliography:

- WILSON, N., (ed.), 2014. Plumes and Pearlshells: the Art of the New Guinea Highlands. Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

- BROWN, P., 1978. Highland Peoples of New Guinea. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- CONNOLLY, B., et ANDERSON, R., 1989. Premiers contacts. Paris, Gallimard.