*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

As Elizabeth Edwards has argued, visual repatriation visual repatriation is, in many ways, about finding a present for historical photographs, realising their ‘potential to seed a number of narratives’ through which to make sense of that past in the present and make it fulfil the needs of the present.”1 Edwards explains how visual repatriation visual repatriation is first a way for both Indigenous people and collections holders to shed light on groups of photographs, usually taken in the 19th and 20th centuries, and try to get information about these photographs. More importantly, visual repatriation visual repatriation can be said to allow one to generate narratives which bridge the gap between past and present.

La visual repatriation Visual repatriation was very often regarded as a one-way process, as repatriated photographs travelled back to Indigenous communities. However, the desire to repatriate can come from either a museum that holds the collection or from Indigenous communities themselves who can claim the return of knowledge regarding their culture.

There is not one single way to repatriate visual repatriation There is not one single way to repatriate – there are as many repatriations as there are cases of visual repatriation. Furthermore, the process usually creates ‘engagement zones’, as defined by James Clifford in his reflection on the museum as a contact zone.2 “What occurs in an engagement zone and what it produces depends upon the collaborative approach used, the participants involved, the way the process unfolds, and the context in which it occurs.”3 In other words, each case of visual repatriation visual repatriation depends on and is determined by the different means of collaboration between the people involved and the context in which the process itself unfolds. “There are as many approaches to engagement as there are museums, communities, and individuals to participate in them”4which makes every zone, or each case of visual repatriation visual repatriation unique. This involves assemblages of visual footage but also assemblages of people and institutions; this is this very combination of elements that places the engagement zone as “semiprivate, semipublic spaces where on-stage and off-stage culture can be shared and discussed and knowledge can be interpreted and translated to enable understanding between those without the necessary cultural capital or to facilitate cross-cultural access.”5 Historian Briony Onciul explains here that the outcome of the engagement zone, visual repatriation visual repatriation in our case, is what allows the whole process to exist.

As every visual repatriation visual repatriation is different from one another, we will discuss what is truly achieved through the visual repatriation visual repatriation of photographs. To gain a better understanding of the question we will explore visual repatriation visual repatriation through two case studies: Joshua Bell’s repatriation of photographs in the Purari Delta in Papua New Guinea and the creation of a new library and database by the Vanuatu Cultural Centre in Port Vila.

Purari Delta, Papua New Guinea

Map of New Guinea, Purari Delta © CASOAR

According to Elizabeth Edwards, “photographs, especially of the kinds that have historically entered European and American museum collections, are almost always, for better or worse, a site of intersecting histories”.6 It is with a view to understanding these “intersecting histories” that Joshua Bell went back to the Purari Delta area to bring back an assemblage of fifty-eight photographs taken by Alfred Haddon and his daughters in 1914 and seventy-six prints taken by Francis Edgar Williams in 1922. According to Bell, the visual repatriation visual repatriation of these photographs “has emerged as another aspect of photographs’ social lives.”7 Of course, the photographs reveal information about the time and the context when they were taken. But they also became entangled in a process which tells the different stories of the people in the photographs rather than the stories of the colonizers that took the photographs.

Bringing back the photographs is much more than bringing back mere photographic artefact. It is no doubt a way of bringing the people themselves back to their territories, which is why Joshua Bell’s arrival in the Purari region “was framed as part of the return of a mythical lost young brother’s descendant.”8 Framing the return of the photographs was a way for the Purari people to understand and acknowledge the return of so many ancestors at once. But more than just bringing back ancestors to their society, the repatriation of these photographs was a way for Purari people to prove who is an amua (class of chief) and who is not.9 Indeed, the photographs of the moments from the past are taken for granted as showing the truth of a time which is now over.

Elder Ikoi Uaini answers questions from interested kinsmen about a photograh taken by F. E. Williams in 1922 during a public viewing in Mapaio. © Joshua A. Bell, 2002.

The viewings of the photographs happened in two stages: first a public viewing and then an individual viewing. In both cases, people asked for the location in which the photographs were taken, as if geographical contextualisation was a key element to be able to read these photographs. In public viewings, people usually discussed ceremonies, songs, the use of objects, everything that was linked with common memory. In private viewings, people focused more on the names of the people and how they were related to their family. This double understanding of a same moment in time is what Joshua Bell has called the “plural frames of history”.10

Keneva Henry Ke’a and Joshua A. Bell examining a map of the Purari Delta made with datum points collected in March 2010, subsequently sent back to local communities. © Natasha Jones, 2011

The encounter with the photographs and therefore with their ancestors led Purari people to interact with these images. When one image would make people sing, another would make them use similar objects to the ones depicted in the picture. But reactions could be even more intimate in private settings – people touched the photographs, cried over them, hugged them or embraced them. Discovering these photographs and interacting with them was a way for the elders of bridging the gap between past and present. As Edwards argues, “photographs become a form of interlocutor. They literally unlock unlocking memories”.11 Ultimately, rediscovering the stories told by the photographs was also a way of telling and conveying them to younger generations and, in so doing, of creating a connection with the future.

But what happened to the pictures when Joshua Bell left Papua New Guinea? The photographs stayed on their home territory so that they were available for consultation by Papuans inside the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery, but also in all the institutions with a storage unit. The photographs would spread in the country if more institutions opened their doors. As only a small percentage of the Papua New Guinea population can currently have access to these databases for now, fieldwork led by anthropologists stays the most prevalent and fruitful form of visual repatriation visual repatriation in countries with such a situation regarding museums.

Cultural Centre of Vanuatu, Port-Vila

In Vanuatu, even though there are not many more museums exist on the territory, the situation regarding access to collections and the diffusion of knowledge is quite different from what we have just seen about Papua New Guinea and the Purari delta. The Vanuatu Cultural Centre and National Museum plays an important role in local ‘activation’ of the “bank for kastom”.12 In Vanuatu, kastom is a word used to talk about “traditions”.13 To keep kastom activated, the Vanuatu Cultural Centre has worked in collaboration with several museums in the United Kingdom who held photographs taken by John Layard in order to repatriate these images to make them available for Ni-van. Once repatriated, these images have been made available in the Vanuatu Cultural Centre in Port-Vila, but they are not fully accessible to everybody. Indeed, there is a Tabu which is regulated by the rules of kastom which allows the Cultural Centre to keep control of who is allowed to look at certain images. Rules of kastom have indeed a role to play in repatriation. Repatriation is also a way for Indigenous people involved to redefine the rules of consultation: some images could only be accessed by certain people, and only people who were high enough in society were allowed to see the tabu images tabu.

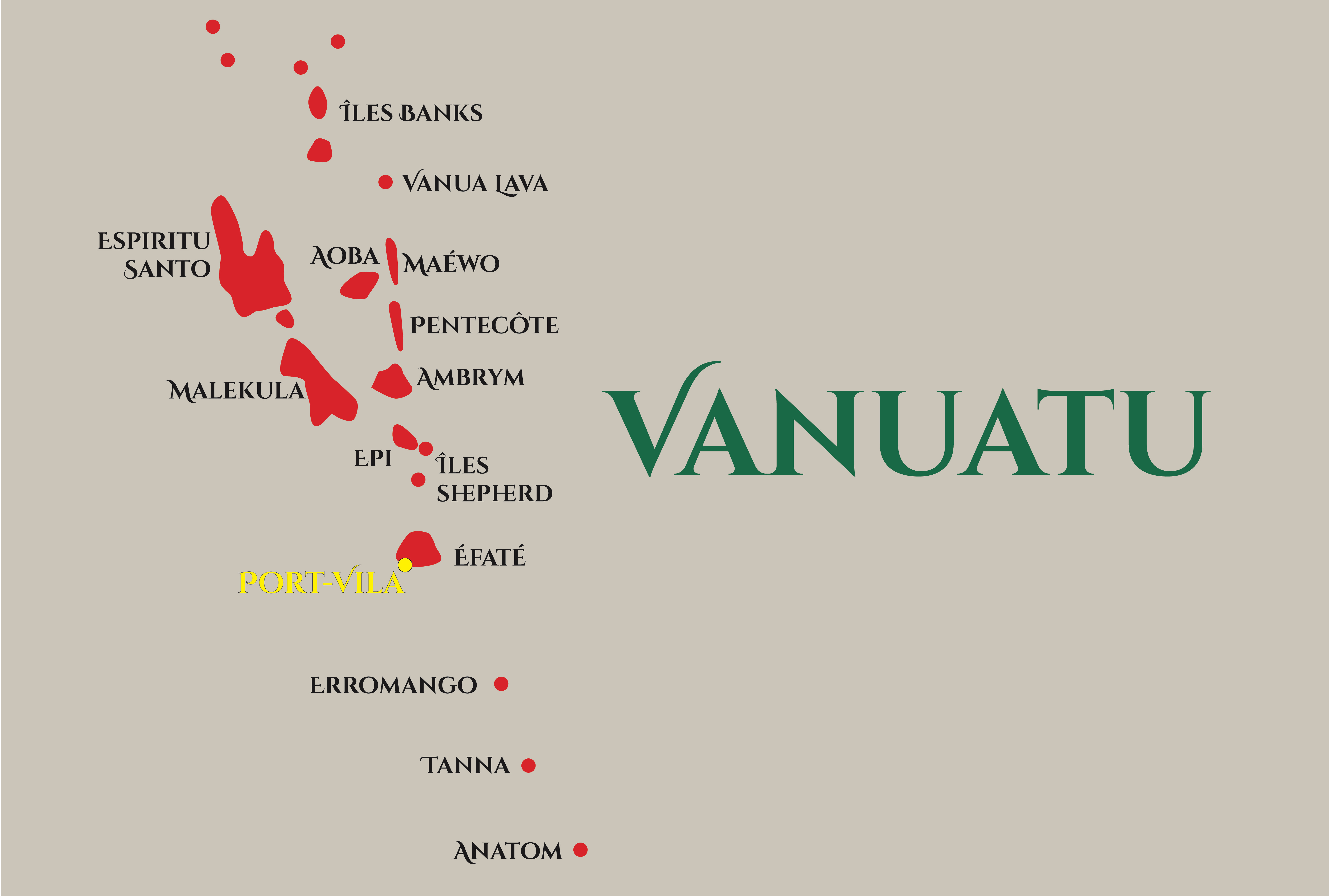

Map of Vanuatu. © CASOAR

The photographs have not just been reclassified but have also been reused in new projects in order to create new interactions between people and images and even create new objects. Indeed, the photographs have been used to revive the production of barkcloth in Erromango, the making of mats on Ambae, male ceremonies in Southern Malakula and the practice of sand-drawing in Malakula, Pentecost and Ambae.14 The repatriation of Layard’s photograph has “facilitated the growth of a dynamic contemporary art movement”15 in Vanuatu, thanks to the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, the instigator of the project. All these new creations represent a big achievement for Vanuatu as most of these practices have been registered in the UNESCO Convention on Intangible Cultural Heritage. The photographs have been a way to convey knowledge of kastom through generations.

John Layard, Dancing ground showing gongs, and the fence built around the large flat dolmen in connexion with the death of an old man.” Togh Vanu, Vao, 1915. CUMAA N.98803. Reproduced with kind permission of the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

According to Haidy Geismar, Layard’s images have even allowed to do some sort of archaeology: sometimes objects like slit-drums were represented in the photographs and by looking carefully at the landscape, behind bushes, some objects that had been hidden for years were ‘found’ again.16 But more than ‘proper’ archaeology, Geismar argues that Layard’s photographs have been used as a way to “excavate narrative” in order to reconnect with places.17 Ni-van have also used the photographs to recreate scenes of the past and inscribe them into the present. Recreating both moments and objects from other times have allowed the repatriated photographs to be part of a nexus of new agencies that have only been possible thanks to the process of gathering as many elements of kastom as possible from museums throughout the world in the form of images, videos and even sound recordings.

Jean Mal Varu and Harris Melteas, Togh Vanu nasara, Vao, standing at the site of Layard’s photograph, reconnecting as the descendents of the slit-drums within. © Haidy Geismar, 18 July 2003.

With time, Layard’s images have with time been used a lot in the local press and they continue to be used even outside of the kastomsphere, as elements for anthropologists to come and study to gain better understanding of Ni-van culture. As a result of the visual repatriation visual repatriation done in collaboration with several museums and libraries, the Vanuatu Cultural Centre now holds the world’s largest collection of visual material related to Vanuatu.

“Ethnographic films hold great historical value for the communities in which they were filmed, yet people in source communities often lack access to them.”18 While this statement by Andrew J. Connelly refers to films, it can also resonate with both our case studies.

The photographs brought back by Joshua Bell to the Purari Delta area are definitely of great historical value for the community. One of the first reasons for this is that the images and what they depicted were taken for granted by the Purari people as ‘shadows of the past’. Another reason for this value is that more than just making people recall of the past, the repatriation of these images made people revisit and rethink the way they were acting, dancing and singing. With this look on the past, Purari people have been able to revive certain songs and use certain objects as a way for them to testify to the continuity of their culture, even after colonization.

In terms of revival, thanks to this historical value, the case of the Vanuatu Cultural Centre is quite straightforward. Indeed, several practices of old kastom were put back in the spotlight and are now, again, part of the intangible cultural heritage of Vanuatu. Layard’s photographs coming back to their homeland have been mainly about making something new out of old things: old photographs have been recreated in order to open dialogue between people and to make the kastom alive and active again. But the most significant part of the repatriation project was to have this material made visible and accessible to the original communities, and for these people to be able to interact with it.

To some extent, one could argue that these two case studies have allowed us to see how visual repatriation visual repatriation repatriation is a process that involves past, present and future at the same time. While Purari people looked at the past in order to understand the present, Ni-van people used the past to construct and create a new present, as if the past was feeding and generating new achievements.

Clémentine Débrosse

Cover picture: Chief Paulo Clem and schoolchildren looking at Layard’s photographs, Senhar station, Atchin, 22 July 2003. © Haidy Geismar

1 EDWARDS, E., 2003. ‘Locked in the Archive’. In: In PEERS, L., and BROWN, A. K., eds., Museums and Source Communities: a Routledge Reader. London, Routledge, p. 84.

2 ONCIUL, B., 2013. ‘Community Engagement, Curatorial Practice, and Museum Ethos in Alberta, Canada.’ In: GOLDING, V., and MODEST, W., Museums and Communities: Curators, Collections and Collaboration. London, Routledge, p. 79.

3Ibid.

4 ONCIUL, B., 2013. ‘Community Engagement, Curatorial Practice, and Museum Ethos in Alberta, Canada.’ In: GOLDING, V., and MODEST, W., Museums and Communities: Curators, Collections and Collaboration. London, Routledge, p. 81.

5 ONCIUL, B., 2013. ‘Community Engagement, Curatorial Practice, and Museum Ethos in Alberta, Canada.’ In: GOLDING, V., and MODEST, W., Museums and Communities: Curators, Collections and Collaboration. London, Routledge, p. 84.

6 EDWARDS, E., 2003. ‘Locked in the Archive’. In: In PEERS, L., and BROWN, A. K., eds., Museums and Source Communities: a Routledge Reader. London, Routledge, p. 83.

7 BELL, J. A., 2003. ‘Looking to See: Reflections on Visual Repatriation in the Purari Delta, Gulf Province, Papua New Guinea.’ In PEERS, L., and BROWN, A. K., eds., Museums and Source Communities: a Routledge Reader. London, Routledge, p. 111.

8 BELL, J. A., 2003. ‘Looking to See: Reflections on Visual Repatriation in the Purari Delta, Gulf Province, Papua New Guinea.’ In PEERS, L., and BROWN, A. K., eds., Museums and Source Communities: a Routledge Reader. London, Routledge, p. 112.

9 BELL, J. A., 2003. ‘Looking to See: Reflections on Visual Repatriation in the Purari Delta, Gulf Province, Papua New Guinea.’ In PEERS, L., and BROWN, A. K., eds., Museums and Source Communities: a Routledge Reader. London, Routledge, p. 114.

10 BELL, J. A., 2003. ‘Looking to See: Reflections on Visual Repatriation in the Purari Delta, Gulf Province, Papua New Guinea.’ In PEERS, L., and BROWN, A. K., eds., Museums and Source Communities: a Routledge Reader. London, Routledge, p. 115.

11 EDWARDS, E., 2005. ‘Photographs and the Sound of History’. Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 21, no 1 and 2, p. 39.

12 GEISMAR, H., 2009. ‘The Photograph and the Malanggan: Rethinking images on Malakula, Vanuatu’. Australian Journal of Anthropology, vol. 20, issue 1, p. 55.

13 Voir DEBROSSE, C., 2020. « Existe-t-il une créature répondant au nom de « culture traditionnelle » ?* ». CASOAR: https://casoar.org/2020/03/25/existe-t-il-une-creature-repondant-au-nom-de-culture-traditionnelle/

14 GEISMAR, H., 2009. ‘The Photograph and the Malanggan: Rethinking images on Malakula, Vanuatu’. Australian Journal of Anthropology, vol. 20, issue 1, p. 56.

15Ibid.

16 GEISMAR, H., 2009. ‘The Photograph and the Malanggan: Rethinking images on Malakula, Vanuatu’. Australian Journal of Anthropology, vol. 20, issue 1, p. 64.

17Ibid.

18 CONNELLY, A. J., 2016. ‘Pikisi Kwaiyai! (pictures tonight!): The Screening and Reception of Ethnographic Film in the Trobriand Islands, Papua New Guinea’. Australian Journal of Anthropology, vol. 27, issue 1, p. 3.

Bibliography:

- BELL, J. A., 2003. ‘Looking to See: Reflections on Visual Repatriation in the Purari Delta, Gulf Province, Papua New Guinea.’ In PEERS, L., and BROWN, A. K., eds., Museums and Source Communities: a Routledge Reader. London, Routledge, pp. 111-121.

- BELL, J. A., 2014. ‘The Veracity of Form: Transforming Knowledge and their forms in the Purari Delta of Papua New Guinea’. In SILVERMAN, R., Museum as Process: Translating Local and Global Knowledges. London, Routledge, pp. 105-122.

- BOUQUET, M., 2012. Museums: A Visual Anthropology. London, Berg.

- CONNELLY, A. J., 2016. ‘Pikisi Kwaiyai! (pictures tonight!): The Screening and Reception of Ethnographic Film in the Trobriand Islands, Papua New Guinea’. Australian Journal of Anthropology, vol. 27, issue 1, pp. 3-29.

- EDWARDS, E., 2003. ‘Locked in the Archive’. In: In PEERS, L., and BROWN, A. K., eds., Museums and Source Communities: a Routledge Reader. London, Routledge, pp. 83-99.

- EDWARDS, E., 2005. ‘Photographs and the Sound of History’. Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 21, no 1 and 2, pp. 27-46.

- GEISMAR, H., 2009. ‘The Photograph and the Malanggan: Rethinking images on Malakula, Vanuatu’. Australian Journal of Anthropology, vol. 20, issue 1, pp. 48-73.

- GEISMAR, H., and HERLE, A., (eds.) 2010. Moving Images: John Layard’s, Fieldwork and Photography on Malakula Since 1914. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press.

- GORDON, O., 20 février 2017. ‘By Way of Anthropology: Museum’s Photos Go on an Extraordinary Journey Home’. Oxford Today.

- ONCIUL, B., 2013. ‘Community Engagement, Curatorial Practice, and Museum Ethos in Alberta, Canada.’ In: GOLDING, V., and MODEST, W., Museums and Communities: Curators, Collections and Collaboration. London, Routledge.