*Switch language to french for french version of the article*

It is hard to think you would just happen to be walking by the Opale Foundation without previously planning to go visit it! Perched at an altitude of 1,100 meters in a village in the Swiss Alps, you first have to negotiate a few hairpin bends to finally arrive at your destination: the Valais commune of Lens. Even before entering the art center, the visitor can appreciate the natural setting; the Rhone Valley below, snow-capped peaks on the horizon and their reflection in Lake Louché, which borders the Foundation.

Designed by Swiss architect Jean-Pierre Emery, the building is intended to fit into this environment in such a way as to enhance it. The mirror-like facade of the art center responds to the shimmer of the lake also reflecting the surrounding mountains. The green roof completes this "erasure" of the building into the landscape.

Opale Foundation – © Olivier Maire

First occupied by the Pierre Arnaud Foundation from 2013, the Lens Art Center was then taken over by the Opale Foundation, which inaugurated its first exhibition in 2018. The birth of this foundation is mainly due to Bérengère Primat, a resident of a neighbouring town and collector of Aboriginal art (Collection Bérengère Primat, more than 1100 works by 250 different artists). The Opale Foundation aims to "enhance the value of the Lens Art Center and become one of the reference institution for contemporary Aboriginal art in Europe"1. The foundation is therefore interested in the development of the local area : they participate in the cultural and tourist offer of the region by producing exhibitions of international dimension, whether in terms of the artists presented or the curators involved. It is chaired by Bérengère Primat, its operational director is Gautier Chiarini and the curator is Georges Petitjean. The foundation owns some works that reside in and around the building, including ghost nets from the Ceduna Art Collaborative, but they do not have an exhibition space dedicated to permanent collections. It also acts as the repository of Bernard Lüthi, an artist, activist and curator (including of the famous exhibition Magiciens de la Terre) who has contributed to the recognition of Aboriginal art in Europe throughout his career.

The Art Centre operates with two spaces (1060m² of exhibition space in total): a large space on two levels for the main exhibitions and an adjoining room that hosts "special focuses" devoted to a particular work by an artist or collective. Productions by Michael Cook and Robert Fielding, among others, have been shown here, as well as those of other artists who are not necessarily of Aboriginal origin. In the other space, the Opal Foundation presents temporary exhibitions which stay open for about 10 months which is rather long compared to other institutions.

After a first major exhibition introducing Aboriginal art (Before Time Began, exhibition also presented in Bruxelles) which evoked the notion of Dreamtime and the genesis of contemporary Aboriginal art, the second major exhibition (Résonances) proposed to put in relation Aboriginal works with those of artists of various origins through cosmogonic themes. In both exhibitions, we find works by Aboriginal artists that go beyond the classic medium of painting on canvas or bark and a dialogue with productions by non-Aboriginal artists. They are interesting proposals that highlight the dynamism of contemporary Aboriginal creation and its participation in the world panorama of contemporary art.

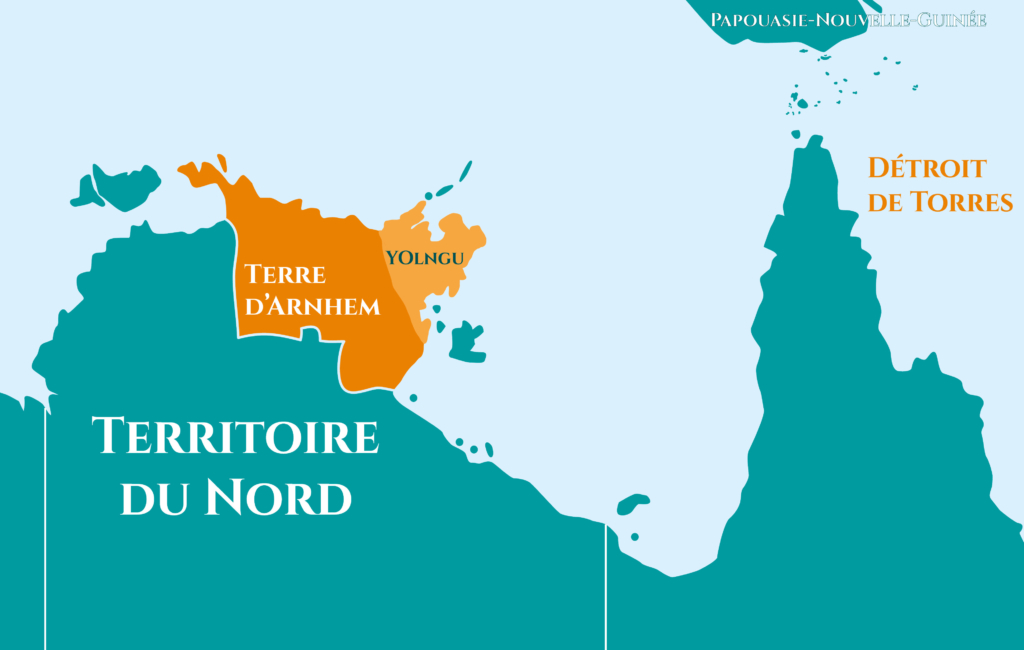

These same directions are reflected in the exhibition currently on show at the Opale Foundation: Breath of life – la vie n’est qu’un souffle from 13.06.21 to 17.04.22), which is devoted to the Yidaki, a musical instrument emblematic of Aboriginal cultures, often better known as the didgeridoo. The exhibition is anchored in Yolngu land, a region in the north-east of Arnhem Land (Northern Territories). Combining material productions, videos and mapping techniques, it offers a discovery of the instrument through the eyes of contemporary Yolngu artists, musicians or visual artists.

Yidaki is the name given to the didgeridoo by the Yolngu people. The Yolngu are the first inhabitants of the region, numbering around 4600 people. They are divided into about thirty clans sharing a semi-nomadic way of life and common beliefs until the middle of the 20th century. However, the groups are differentiated by the languages or dialects spoken. There are about six languages and twelve dialects belonging to the Yolngu Matha language family. Like other Aboriginal peoples, the social organisation of the Yolngu peoples is governed by very strict kinship rules. The Yolngu people are divided into two halves: Dhuwa and Yirritja, which in turn are subdivided into numerous sub-groups commonly known as clans. Members of the same clan share a common territory and common myths.

Carte de la région des peuples Yolngu – © CASOAR

The exhibition is organised in two parts which are spread across two different floors. On the first floor, the first half of the exhibition is devoted to the Yidakiobject. On the ground floor, the second half focuses on sites (see the importance of topography to Aboriginal people here) associated with the instrument as seen through the works of contemporary visual artists.

The first part of the exhibition mainly combines video and yidakimedia. The visitor discovers, among other things, the process of making the instrument: from the choice of the tree to be felled to the painting of the motifs, the breathing techniques necessary for playing as well as the uses of the instrument, from ritual to curative, showed and explained through an extract from a Morning Star report (yet to be published) dealing with a study on the healing potential of the Yidaki at Hammersmith Hospital in London. Djalu Gurruwiwi (b. 1930), currently considered the greatest Yidakiplayer, is given a prominent place in the exhibition. He also has a role as "keeper of the instrument" (keeper of the associated knowledge) and spiritual leader. In a film created for the exhibition, Djalu Gurruwiwi calls for universal reconciliation and unity around the Yidaki. Today, his three sons, Larry, Vernon and Jason, also Yidakiplayers, are carrying on with the role he was occupying as “keeper of the instrument”. The exhibition also honours the object by presenting sets of Yidaki from different clans on circular platforms: an opportunity for the visitor to appropriate the instrument while observing the formal similarities and differences. In addition, there are bilma, percussion instruments also known as clapsticks . These instruments are inseparable from the Yidakiand are used to maintain the rhythm during songs and musical performances. The instruments come mainly from private collections, including the Christian Som and Michiel Teijgeler collections.

View of the exhibition, yidaki are displayed vertically on circular platforms – © Margot Kreidl

The second part of the exhibition is rooted in the Gängän territory and shows four artists and a collective to highlight important sites associated with Yidaki. The first site is the billabong (pond in the Yolngu language) of Garrimala, which borders the territory of Gängän. The place appears in the myths and songs of the Gälpu clan to which the artist Malaluba Gumana (1954-2020) belongs. Gumana anchors her work in Garrimala through her clan's own motifs: the dhatam (water lily), the djari (rainbow) and the djaykung (sea serpent). She also uses marwat, fine cross-hatching that gives the work a vibrant appearance, known as rarrk in other parts of Australia. The exhibition features a canvas and a set of larrakitj, ossuaries or burial posts, painted by the artist. These posts are placed on a platform that recalls the shape of a pond and on which a mapping made by The Mulka Project is projected, suggesting the shimmering of water.

The second artist featured in this part of the exhibition is Gunybi Ganambarr (1973-). Yidaki player and visual artist, he has lived in Gängän all his life and is one of its myth bearers. While his first works were done with natural pigments on bark, as is customary in Arnhem Land, he is now experimenting with new techniques, using recycled materials found in the vicinity of nearby mining operations. Beyond the innovations, the artist has not abandoned his heritage, anchoring his work in the territory of Gängän as much by the motifs used and associated myths as by the materials used, which, although originating from industry, are today an integral part of the Gängän landscape. The exhibition presents a set of hollow log or funeral poles, a monumental work on aluminium plate and two works on insulation panels.

View of the exhibition, in the foreground: larrakitj (funeral posts or ossuaries) by artist Malaluba Gumana, in the background: work on aluminium panel by artist Gunybi Ganambarr – © Margot Kreidl

In the last room of the exhibition, visitors are greeted by strange, wiry figures with pointed ears, protruding ribs and waving legs (respecting the original shape of the branches). In addition to these works by Nawurapu Wununmurra (1952-2018), a group of more static characters created by his son, Bulthirrirri Wununmurra (1981-), are displayed in the center of the room. Finally, a video mapping created by the Yolngu collective The Mulka Project in collaboration with Bulthirrirri Wununmurra is associated with this production. Projected onto a large transparent canvas arranged in a circle around Bulthirrirri Wununmurra's sculptures, the mapping reveals moving silhouettes. The whole room evokes the presence of the mokuy, ancestral spirits associated with the dead. For the Yolngu, they are said to be the source of the transmission of manikay. They are also said to be able to produce sounds similar to the YidakiThe artists also refer to the sacred site of Balambala (also in Gängän territory). Considered as one of the meeting points of the mokuy, this site is used to relay the announcement of a death and to call on the spirits and men of all clans for the funeral ceremonies through the sound of the Yidaki.

View of the exhibition, left: mokuy sculptures by Nawurapu Wununmurra, right: video mapping by The Mulka Project – © Margot Kreidl

It was a great pleasure to discover the beautiful Opal Foundation and its exhibition Breath of life – la vie n’est qu’un souffle. We were delighted to see an exhibition dedicated to contemporary Aboriginal art that featured productions other than paintings, as well as Arnhem Land artists who are sometimes overlooked in favour of central desert artists. We were also excited by the selection of objects on display and in particular by the presence of works by Gunybi Ganambarr, Nawurapu Wununmurra, Bulthirrirri Wununmurra and the Mulka Project. Indeed, we were familiar with the productions made with natural pigments on eucalyptus, but thanks to the Foundation's exhibition, we discovered these artists who are seizing new mediums and daring new formal proposals. Finally, we can only recommend this exhibition to everyone, with its accessible and well constructed subject matter. Do not hesitate a second and go discover both the Foundation and the exhibition!

As for us, we will be back soon with a new article focusing on the didgeridoo.

Morgane Martin & Margot Kreidl

1 Dossier de presse de l’exposition « La vie n’est qu’un souffle », p. 14.